In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, May 11, 2025, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

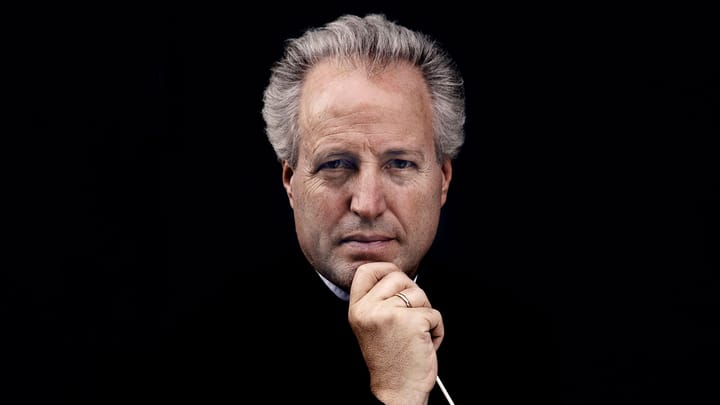

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

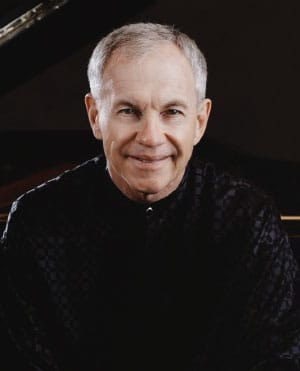

Anton Nel piano

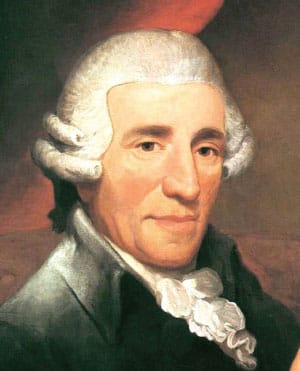

Joseph Haydn

Piano Trio in G major, Hob.XV:25 (1795)

Andante

Poco adagio

Finale: Rondo all’Ongarese: Presto

Frank Bridge

Phantasie for Piano Trio (1907)

Allegro moderato ma con fuoco–

Andante con molto expressione–

Allegro scherzoso–

Andante–

Allegro moderato–

Con anima

Intermission

Felix Mendelssohn

Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Opus 66 (1845)

Allegro energico e fuoco

Andante espressivo

Scherzo: Molto allegro, quasi presto

Finale: Allegro appassionato

The Chamber Music Series at the Legion of Honor is supported by Ann Paras.

This series showcases the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin on loan to Alexander Barantschik and the San Francisco Symphony from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Program Notes

Piano Trio in G major, Hob.XV:25

Joseph Haydn

Born: March 31, 1732, in Rohrau, Austria

Died: May 31, 1809, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1795

Joseph Haydn composed his G-major Piano Trio, Hob. XV:25, in the summer of 1795, near the end of his second residency in London, and from the outset it has been a popular favorite, thanks especially to its vivacious finale. The first movement seems Mozartian in the tunefulness of its opening theme, and Haydn subjects this unencumbered melody (with its arresting bass line) to much elaboration in the course of variations. The melody is imaginatively presented first in G major, then in G minor—the two faces of G—and the variations proceed in a “double form,” always reflecting that balance of major and minor (though the second minor variation provides variety by being cast in the related key of E minor).

The beginning of the Poco adagio is more what early Haydn trios had sounded like from a textural point of view, with the piano front and center and the violin and cello hovering in the background—although a less mature and experienced composer might not have captured quite the same combination of simplicity and expression, which here combine to poignant effect. The violin emerges in the central cantabile section, which seems hardly less dreamlike than corresponding poetic expanses that will lie ahead in the more Romantic effusions of Schubert and Schumann. This is an exceptionally beautiful slow movement, even for Haydn. That it is set in E major clarifies why one of the variations in the opening movement had surprised us by being in E minor; we understand retroactively that it was not a passing fancy but rather the first step toward making this entire trio a well-woven whole.

But it is the vivacious finale that cemented this trio’s status as a popular favorite from the get-go. It’s a tour de force in the so-called “Hungarian style” that was wildly popular in Vienna and environs in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Haydn must have lived in proximity to music of this sort during his years at Esterháza in Hungary; one period engraving of the palace in Esterháza shows a Romani band playing at the edge of the scene. In the G-major Trio, the source of the finale theme has proved elusive, but its contours suggest music that might have emanated from Komitat Veszprém (a county of Western Hungary perhaps 50 miles southeast of Esterháza) and particularly from the tradition of the verbunkos, dances that figured in the process of military recruitment. The Austrian soldiers, wearing elegant uniforms, would entertain unsuspecting Hungarian peasants with vigorous music, athletic dances, and abundant alcohol, at which point life in the regiments must have seemed irresistible. One of the themes in Haydn’s finale—the swaggering minor-key bit (over a cello drone) that falls just at the movement’s mid-point and returns near the end—relates to a melody found in a collection of Hungarian national dances for piano that was issued in Vienna in four volumes beginning in 1805. It seems to give credence to the authentic folk origins of Haydn’s piece, though a nagging “chicken-and-egg” question does surround such matter; sometimes composed melodies become adopted into the popular repertoire and are assumed to be folk pieces when they aren’t really.

Haydn dedicated this trio to Rebecca Schroeter, an amateur pianist and the widow of a composer. They had met during Haydn’s first residency in London, often dined together, and apparently became romantically involved—not a unique arrangement for Haydn, who had little in common with his wife and lived largely estranged from her. Haydn described her to his biographer Albert Christoph Dies as “a beautiful and amiable woman whom I might very easily have married if I had been free then.”

Phantasie for Piano Trio

Frank Bridge

Born: February 26, 1879, in Brighton, England

Died: January 10, 1941, in Eastbourne, England

Work Composed: 1907

Frank Bridge is most famous today thanks to another composer—Benjamin Britten, who studied with him from the age of 14, found in him an inspiring mentor, and in 1937 memorialized their teacher-and-student relationship through his own Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra. Although he never achieved the international acclaim of his most famous pupil, Bridge was a far-from-negligible composer and remains widely revered in Great Britain. He received his musical education at the Royal College of Music in London, where he studied composition for four years with the Irish composer Charles Villiers Stanford. In 1906 he worked as substitute violist with the Joachim Quartet (just a year before the death of the group’s founder and first violinist, Joseph Joachim), and for nine years, from 1908–15, he was a member of the English String Quartet. At the same time, his status as a conductor was growing, not only with the newly founded English String Orchestra but also with the London Symphony Orchestra and for opera productions at the Savoy Theatre and Covent Garden. The pieces he composed prior to World War I tended to follow the genteel warmth of the Edwardian era; but during the war years he redirected his style to more modernist paths, embracing a flexible method that allowed for a degree of atonality, bitonality, and rhythmic freedom.

This is one of many “phantasy” pieces produced by British composers in the first half of the century, for a practical reason. Walter Willson Cobbett (1847–1937), a wealthy aficionado who would author the fascinating, quirky Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music (1929), used the word—in its curious spelling—to describe the pieces he invited composers to submit for a competition he founded in 1905. The phantasies were to be rather short, one-movement pieces, though potentially sectional or episodic, analogous to the fantasias of English Renaissance composers. Bridge’s F-minor Phantasy for String Quartet took third place in the inaugural contest. The next competition came two years later, and this time Bridge’s Phantasie for Piano Trio won the top award, with the composer one-upping Cobbett in the matter of “Quainte Spellynge.” He would compose yet another phantasy—a piano quartet in 1910, by which time Cobbett’s competition had morphed into a direct commissioning program.

It was bandied about that Cobbett’s aim was to supplant the primacy of time-honored sonata form. “No such idea ever crossed my mind,” he protested. “They were asked simply to give free play to the imagination in the composition of one-movement works, to write what they liked—in any shape—so long as it was a shape.” Indeed, the chamber-music authority Edwin Evans, writing about this piano trio in Cobbett’s Cyclopedic Survey, described it as “a very good example of the [phantasy] form, which corresponds to a sonata-allegro with an andante displacing to a large extent the usual development, and again a scherzo furnishing a contrasted middle section to the andante.”

Upholding the picturesqueness to which Cobbett was partial, Bridge’s Phantasie Piano Trio was premiered on April 27, 1909, by the London Piano Trio, at a banquet of the Incorporated Society of Musicians, a guild that had been founded in 1882. Cobbett shared his admiration for this piece in a lecture he gave in 1911 to the Concert-goers’ Club: “Mr. Bridge’s Trio is of remarkable beauty and brilliancy, and stamps him as one of our foremost composers for the chamber. With a lavishness to which I can recall few precedents, he has provided thematic material more than sufficient for a lengthy work in sonata form. Packed as it is with interesting matter, it stands the greatest of tests, that of frequent repetition.”

Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Opus 66

Felix Mendelssohn

Born: February 3, 1809, in Hamburg, Germany

Died: November 4, 1847, in Leipzig, Germany

Work Composed: 1845

Felix Mendelssohn achieved expertise as a pianist when he was still a child and throughout his life he composed generously for his instrument, leaving behind an ocean of idiomatic piano writing in solo repertoire, as an accompanying instrument, in chamber music, and in concertos. On January 21, 1832, while he was visiting Paris, he wrote to his sister Fanny, “I should like to compose a couple of good trios.” It appears that he had already written one by that time, a C-minor trio of 1820, which, had it survived, would stand as one of his earliest compositions. In any case, two “good trios” did lie ahead—so good, in fact, that they stand along with Robert Schumann’s D-minor Trio as the genre’s only works from the 1830s and ’40s to remain firmly ensconced in the active repertoire today, notwithstanding the huge popularity piano trios enjoyed during those decades.

The first of Mendelssohn’s, in D minor, Opus 49, appeared in 1839 and was hailed by Schumann as “the master-trio of our time.” The C-minor Piano Trio, Opus 66, followed six years later. The first movement seems in certain ways uncharacteristic of Mendelssohn, whose music rarely sustains an analogous level of nervous tension, announced from the very opening, when the piano, soon seconded by the violin, proclaims the powerful theme above a pedal point in the cello. The second theme is a particularly glorious conception, a melody that holds the potential of joyous triumph in the relative major key of E-flat. This Allegro energico looks forward toward Brahms in its serious mien. In the movement’s coda, Mendelssohn scores a technical bull’s eye by having the strings play an augmented (stretched-out) version of the main theme while the piano plays the theme in its normal proportions—no mean trick.

In the second movement, the piano introduces the introspective, slightly nostalgic melody but then takes more of a back seat as the strings develop the material into an expressive, cantabile, triple-time outpouring. Counterpoint is again prominent in the fleet Scherzo, a chattering toccata enlivened by fugato texture. If the opening recalls the bustling vigor of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream scherzo, its middle section again prefigures Brahms, thanks to the powerful accenting of downbeats (strengthened by trills) and what at moments evokes a “Hungarian” flavor.

The finale begins less like Brahms than like Schumann: in his book Mendelssohn’s Chamber Music, John Horton points out that the opening theme, launched with the huge interval of the ninth, resembles that of Schumann’s piano composition Aufschwung (Opus 12, no.2). A moment of unalloyed Mendelssohn arrives soon enough, however, with the introduction, in the piano, of a chorale—one of the composer’s favorite devices for elevating the tone of spiritual devotion. Here the melody evokes the German Lutheran chorale “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ”—but it’s really no more than an allusion. (Some scholars have instead heard the germ of the traditional chorales “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit” and “Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir,” but to my ears “Gelobet seist du” seems a more obvious jumping-off point.) Much as Brahms, in his ostensible folk-song settings, would often cite only the beginning of a melody before spinning off into an essentially original melody, Mendelssohn here writes his own chorale. After a good deal of deconstruction and reassembly, the melody returns at the movement’s climax, hammered out loudly in rich piano chords against contrapuntal overlapping in the strings—a moment in which the intimate medium of the piano trio seems about ready to explode.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of last season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.