In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, November 16, 2025, at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Trio in E-flat major, Opus 1, no.1 (1795)

Allegro

Adagio cantabile

Scherzo: Allegro assai

Finale: Presto

Variations in G major on “Ich bin der Schneider Kakadu,” Opus 121a (1816)

Introduzione

Tema

Variations I–X

Allegretto

Intermission

Piano Trio in B-flat major, Opus 97, Archduke (1811)

Allegro moderato

Scherzo: Allegro

Andante cantabile

Allegro moderato

Program Notes

Piano Trio in E-flat major, Opus 1, no.1

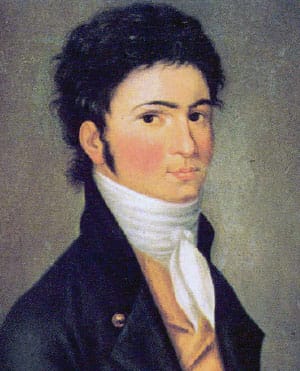

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1795

The sharp opening of Ludwig van Beethoven’s E-flat–major piano trio announced to the world that a new, important composer had arrived: it was this piece he chose to publish as his Opus 1, no.1, in 1795. Of course, it was not actually his first composition, but rather his first major publication in Vienna. Three years earlier, he had moved to the Austrian capital from his sleepy birthplace of Bonn. Arriving a year after Mozart’s premature death, Beethoven arranged to study with Haydn instead. As his patron Count Waldstein put it, “you shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.”

The young Beethoven already had aristocratic support, the public’s attention, and a pile of childhood compositions. He revised and drew from these to create many of his first works in Vienna, sharing them in private performances and through hand-copied manuscripts. The E-flat–major piano trio began its life in this way, perhaps originating in sketches from Bonn and then honed under Haydn’s tutelage, before a premiere in 1795 by Beethoven and two string-playing friends at the house of Prince Carl Lichnowsky. Finally he published the trio, part of a set of three, as his Opus 1: a mark of arrival as much as a point of departure.

The beginning is confident and lithe—a jolt in the three instruments, a sprint upward in the piano, three pointed chords, and another sprint. A repetition, and then a more melodic closure of the phrase. These ideas fill the whole Allegro—while the development of small motifs into extended material is a basic technique of Classical style, the concentration of the trio’s ideas and the variety of their elaboration seem especially Beethovenian.

The slow movement, Adagio cantabile, is songlike, beginning with the solitary piano. The violin and cello respond, tentatively filling out the piano’s sonority, before joining in the song themselves and then continuing off in a new direction. The piano brings back the song, but a darkness passes over, and finally the song returns a third time dressed with embellishments.

The scherzo was a form Beethoven began to favor for his third movements instead of the older, more rustic minuet. This scherzo is a teasey diversion, cutting away to a more placid trio section. It is reprised with a coda that slows to a halt, offering a brief contrast before the next movement starts up again at a fast clip.

The piano calls out inquisitively to begin the finale, in wide ascending intervals that recall the first movement’s upward dashes. Again, Beethoven builds an entire movement from a few concise ideas: the two notes of the piano’s questions, the violin and cello’s response, and a jaunty second theme. Minutes later the first-movement sprint is brought back, unifying the entire trio in a quick flash before a resolute close.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Variations in G major on “Ich bin der Schneider Kakadu,” Opus 121a

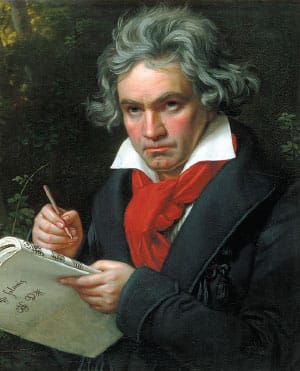

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Work Composed: ca. 1794–1803? (rev. 1816)

“My Dear Herr von Härtel!”—so Beethoven began his letter to the publisher Gottfried Christoph Härtel on July 19, 1816. He continued, trying to establish an advantageous playing field for the business negotiation he envisioned: “Boasting is foreign to my character. So all I can do is offer you the following works: a new sonata for pianoforte solo, variations with an introduction and a supplement for pianoforte, violin, and cello on a well-known theme by Müller. These belong to my early works, but they are not poor stuff.”

The theme on which Beethoven based his variations was the lighthearted song “Ich bin der Schneider Kakadu” (I am the Tailor Kakadu) by Wenzel Müller. The song figured in Müller’s comic singspiel Die Schwestern von Prag (The Sisters from Prague), which was premiered on March 11, 1794, at the Theater in der Leopoldstadt in Vienna, where the Moravia-born composer served as music director. Some scholars assume that Beethoven wrote his variations shortly after the opera was premiered, when the song would have been fresh in everyone’s ears. Others place its composition later, around 1803, but there is rather little to go on when it comes to dating this piece. An 1814 revival of Die Schwestern von Prag may have provided the impetus for Beethoven to dig out the variations he had written long before.

The G-minor introduction runs to about six minutes of somber, emotionally fraught music into which Beethoven embeds adumbrations of Müller’s melody, though so decked out in mourning clothes that a listener could be excused for not recognizing it (and of course the tune itself has yet to be stated). This is a grand bait-and-switch scheme: the extended desolation resolves to Müller’s perky, unsophisticated G-major tune.

Following the introduction and the statement of the theme, the 10 variations unroll along generally Classical lines, sequentially spotlighting different instruments or textures, plumbing the melody’s contrapuntal possibilities (as in the canons of Variations V and VII), deconstructing the theme (Variation VI), subjecting it to syncopation (Variation VIII), switching to minor mode (Variation IX) or a new meter (Variation X). Other ideas are packed into an Allegretto coda—the “supplement” Beethoven added when trying to sell the piece in 1816.

—James M. Keller

Piano Trio in B-flat major, Opus 97, Archduke

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Work Composed: 1811

For most of his life, Beethoven relied on noble patronage to make his living. From the time he moved to Vienna in 1792, he never had a full-time job in service of a court or church, as many composers did, but made his way as a freelancer with support from a collection of admiring aristocrats. These relationships were often complicated, as Beethoven was deeply indignant at the very idea of noble birth. The son of a town musician, he resented those of higher class, at times even promoting the misconception that the “van” in his name—simply a mark of Flemish ancestry—was really the “von” of German aristocracy. At other times, he angrily claimed a kind of artistic nobility for himself, superior to that of princes.

Still, he needed their support, and they recognized that his artistry warranted some leeway in terms of social behavior. The most gracious was the young Archduke Rudolf (brother of the reigning Emperor Francis I), to whom Beethoven taught piano and composition. Their relationship had many dimensions: artist and patron, teacher and student, perhaps even friends. According to the early biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer, Beethoven “often caused great embarrassment in the household of the Archduke,” and finally declared he could not follow all the etiquette and regulations. “The Archduke laughed good-naturedly and commanded that Beethoven be permitted to go his own gait undisturbed—it was his nature and could not be altered.”

Rudolph was rewarded with the dedications of several major Beethoven works: the Fifth Piano Concerto, the Hammerklavier Piano Sonata, and Missa solemnis. But only the B-flat–major trio has absorbed the Archduke into its title, probably in connection with the piece’s grandness. The cello predominates through the first movement, warm with melody. An extended pizzicato section in the second half brings a sneaky color change. The cheerful scherzo comes next, followed by a reverent slow movement with a theme and its four glowing variations. The theme returns in an echo, and then transitions with a jolt directly into the quick rondo finale.

Beethoven finished the Archduke Trio in 1811, but its first performance was put off until 1814. By this time he had mostly given up performing due to his severe hearing loss, but he agreed to play the trio at a pair of charity concerts—his very last appearances as a pianist. The violinist and composer Louis Spohr recalled how Beethoven “pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano he played so softly that whole groups of tones were omitted … I felt moved with the deepest sorrow at so hard a fate.”

—BP

About the Artists

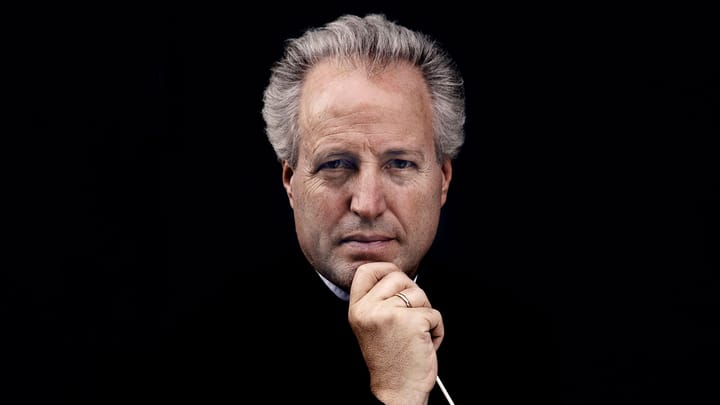

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

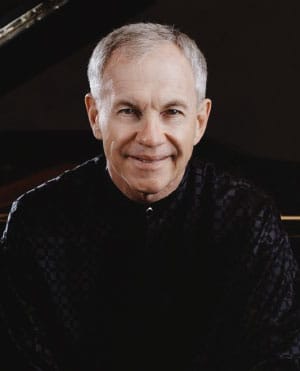

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of the 2023–24 season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.