In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, February 1, 2026, at 2:00pm

Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony

Luigi Boccherini

String Quintet in D major, Opus 37, no.2 (1787)

Allegro vivo

Pastorale: Amoroso, ma non lento

Finale: Presto

Dan Carlson violin

In Sun Jang violin

Gina Cooper viola

Amos Yang cello

Charles Chandler double bass

Arthur Foote

Piano Quartet in C major, Opus 23 (1890)

Allegro comodo

Scherzo: Allegro vivace

Adagio, ma con moto

Allegro non troppo

Kelly Leon-Pearce violin

Gina Cooper viola

David Goldblatt cello

June Choi Oh piano

Intermission

George Enescu

Octet for Strings in C major, Opus 7 (1900)

Très modéré

Très fougueux

Lentement

Moins vite, animé, movement de valse bien rhythmé

Jessie Fellows violin

Olivia Chen violin

Jeein Kim violin

Jane Cho violin

Katie Kadarauch viola

Katarzyna Bryla viola

Anne Richardson cello

Sarah Chong cello

Program Notes

String Quintet in D major, Opus 37, no. 2

Luigi Boccherini

Born: February 19, 1743, in Lucca, Italy

Died: May 28, 1805, in Madrid

Work Composed: 1787

One of the premiere cellists of his time as well as an astonishingly fecund composer, Luigi Boccherini grew up in an artistic family. His father was a singer and a double bass player, his brother a ballet dancer and poet (who penned the libretto for Haydn’s oratorio Il ritorno di Tobia), and his sister a solo dancer who worked in Vienna. After studying cello in Rome, Boccherini returned to his native Lucca, where one of his mentors was Giacomo Puccini, a local organist and (unbeknownst to him) great-grandfather of the Giacomo Puccini. Soon the young cellist was touring farther afield in Italy, and then to such destinations as Vienna and Paris. He was acclaimed as a phenomenal soloist, though a few listeners complained about the harsh vehemence of his playing.

He had intended to travel from Paris to London, but at the last minute he changed his plans and journeyed south to Spain. It was a fateful decision, and Spain would become his center of operations for the rest of his career. In 1770 he was named composer “chamber virtuoso” of Infante Luis Antonio Jaime de Boubón in Aranjuez, and shortly after Luis’s death in 1785 he accepted a position as staff composer to Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, who had long admired Boccherini’s work and was amenable to an arrangement whereby he might fulfill his duties long-distance from Spain. The composer also maintained relationships with the Spanish kings Carlos III and Carlos IV, the latter being a particular enthusiast of music. Boccherini’s final years were difficult. His royal patrons were dying off and it was a far from ideal time for royalty in general, what with the French Revolution and all that. Members of the Bonaparte family eventually took Boccherini under their wing, to a degree, but he finished his days in straitened circumstances in a small apartment in Madrid. His estate included two Stradivari cellos.

Boccherini is most famous for chamber music, including 100 string quartets and nearly 150 string quintets. The work played on this concert is the second in a set of three quintets composed, or at least copied out in the surviving holograph, in 1787—the first being dated January, the second February, and the third March. Boccherini’s string quintets are typically scored for two violins, viola, and two cellos. This set, however, calls for the combination of two violins, viola, cello, and obbligato double bass, standing as a unique triptych in his vast output. This D-major quintet was not published until 1811/12, when the Parisian firm of Pleyel issued it in the more standard layout with two cellos and also provided an alternate part for “alto violoncello,” with which it could be played by two violins, two violas, and one cello. Still, the composer’s autograph score leaves no doubt that he intended the instrumentation used here.

Boccherini’s style typically includes rhythmic syncopation (sometimes repeated over and over), short melodic phrases, abrupt changes in texture and dynamics, and a preponderance of filigree in the principal melodic lines, which tend to unroll over harmonies that are not inherently complex. These traits are especially prominent in the first and third movements, and the first also includes some characteristic writing in which several string instruments join to impersonate the strummed chords of a guitar—surely popular with Spanish listeners. In between comes a lilting Pastorale, its rustic character reinforced by drones in the lower parts that imitate a bagpipe or hurdy-gurdy. Throughout this quintet, Boccherini is careful to include passages to spotlight his own instrument, the cello.

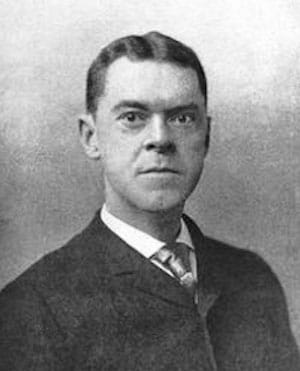

Piano Quartet in C major, Opus 23

Arthur Foote

Born: March 5, 1853, in Salem, Massachusetts

Died: April 8, 1937, in Boston

Work Composed: 1890

Arthur Foote was the first American composer writing under the influence of classical European models to achieve eminence without the benefit of European training. After completing a harmony course at New England Conservatory, he headed to Harvard, where he studied with the distinguished composer John Knowles Paine (to whom he would dedicate his Piano Quartet), led the Harvard Glee Club, and, in 1875, became the first recipient of a master’s degree in music from an American university. He traveled to Europe eight times in the period 1876 to 1896. During his first visit he attended the inaugural season of Richard Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival, and over the years he imbibed the vibrant concert culture of Germany, Great Britain, and France. In Paris in 1883, he took a few formal lessons from the eminent Hungarian pianist Stephen Heller (focusing on Heller’s compositions), the brief “exception that proves the rule” when it comes to his all-American education.

His principal teacher was the Boston musician B.J. (Benjamin Johnson) Lang, who earned a footnote in music history by conducting the world premiere (in 1875, in Boston) of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Lang was acclaimed as a pianist and organist, and Foote followed his lead by working as a church organist, serving in the loft at Boston’s First Unitarian Church for 32 years (1878–1910). He was a founding member of the American Guild of Organists in 1896 and served as its president from 1909 to 1912. Nonetheless, he viewed piano as his principal instrument, and for many years he enjoyed a busy concert career as a pianist in both solo recitals and chamber music.

Foote became especially associated with the Boston-based Kneisel Quartet and its first violinist, Franz Kneisel, who was concertmaster of the Boston Symphony and a leading force in American chamber music. Foote recalled in his memoirs:

In the wonderful days of the Kneisel Quartet (say, 1890 to 1910) I played with it a good many times, chiefly at first performances of my own compositions. Not only had I the honor and happiness of having a hearing for my Violin Sonata, Piano Trio in B-flat, Piano Quartet and Quintet, and String Quartet, but also learned much from Kneisel through his suggestions as to practical points in composition, and I became aware of a different and higher standard of performance through my work with him in rehearsal.

Foote completed the Piano Quartet in August 1890 and unveiled it in Boston on April 21, 1891, assisted by members of Kneisel’s foursome. In 1893, he and the Kneisels would include this work in a program at the Chicago World’s Fair, and by the time he retired from the concert stage, Foote logged 40 performances of the piece.

His music displays a conservative bent. This was his authentic voice and did not reflect a lack of interest in modernist tendencies taking place during his lifetime. In a memorial tribute penned in 1937, the Boston music critic Moses Smith cited a friend who “was amazed by Foote’s curiosity about what was happening among European composers of the advance guard,” and specifically about “Alban Berg, a composer whose training and artistic methods were at the furthest remove possible from those of Foote.” In another obituary, the composer Frederick Jacobi wrote, “In Arthur Foote, American music has lost its last Victorian.” Though not on the cutting edge even in 1890, the Piano Quartet impresses with its technical fluency and warmhearted spirit. The eminent 19th-century chronicler John Sullivan Dwight particularly praised the work’s finale: “Clear, spontaneous, consistent, well wrought, especially in the contrapuntal passages near the end, it satisfied the musical sense.”

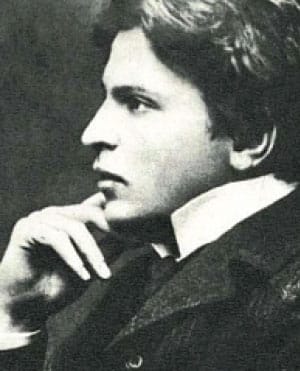

Octet for Strings in C major, Opus 7

George Enescu

Born: August 19, 1881, in Liveni Vîrnav, Romania

Died: May 4, 1955, in Paris

Work Composed: 1900

If you were to look for the village of Liveni Vîrnav on a modern map of Romania, you would not find it. It changed its name in the last century to honor its most celebrated native son, which is why today that spot on the map is identified by the name George Enescu. He began studying violin at the age of four and was only seven when he entered the Vienna Conservatory. After completing his studies there in 1893, he moved to Paris, where the Conservatory ushered him through the composition studios of both Jules Massenet and Gabriel Fauré. France and Romania exerted roughly equal pull on him through much of his career, but when the Communist Party assumed control following World War II, he left Romania for good and lived his remaining decade in exile.

He flourished as a performer—as a violinist, a pianist, a chamber musician, and a conductor. While on tour in San Francisco in 1925, he met the youngster who would become his most acclaimed pupil, Yehudi Menuhin. Indeed, Menuhin would be one of the few to benefit from his expertise on an extended, first-hand basis, since Enescu avoided teaching commitments apart from master classes.

Early in his career, Enescu proved chameleon-like in essaying the various musical approaches then prominent: incorporating folkloric elements into classical works, building on the Germanic solidity of Schumann and Brahms, exploring transparent textures à la Saint-Saëns and Fauré, developing a sort of neo-Classicism some years before Stravinsky and Prokofiev looked in that direction. Post-Wagnerian chromaticism came to the fore in his Octet for Strings (1900, apparently premiered that December 18 in Paris) and his Symphony No. 1 (1905), as did the chromatic modernity of Richard Strauss in his Symphony No. 2 (1914).

The Octet suggests a personal style not yet fully formed, particularly in its tendency to make sudden allusions to definable styles of other composers—its occasional Wagnerisms and Dvořákisms, but especially its Brahmsisms and Wolfisms. On the other hand, this early work also suggests a distinctive voice that would become pervasive in ensuing works. “What is important in art is to vibrate oneself and make others vibrate,” he would later observe; and, on another occasion, “Something trembles in my heart incessantly, both night and day.” A sense of nervous energy, of fluttering, underscores page after page of the Octet. The work’s drama is borne proudly by a “double string quartet” that can approach symphonic textures. At the end of the first movement, a big-boned piece in sonata form that shows off the composer’s adeptness with tightly knit linear (sometimes even canonical) writing, the second cello sustains a low B (achieved by tuning the bottom string down) for 10 measures, as the music winds down and fades away above it.

The second section—the Octet’s four parts are not separated decisively—is marked Très fougueux (Very Impetuous), an unusual but absolutely apt descriptive for this music of propulsive rhythms and often angular melodies. The slow third section (Lentement) strikes a more muted pose, again with suggestions of canon in its interweaving lines; and yet the frequently pulsating lower lines convey even here an underlying tension notwithstanding the remarkable beauty of its melodies. Only in the final minutes of the movement does the mood change, with the upper voices finally expressing only optimism as the lower voices accompany with light-hearted pizzicatos. But the levity is short-lived, and the transition to the fourth section injects the sense of anxiety that will be familiar by now. The craggy principal theme of this finale gives way to sort of drunken waltz.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

Dan Carlson joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2006. He currently serves as Principal Second Violin, occupying the Dinner & Swig Families Chair. He previously served as rotating concertmaster for the New World Symphony and he has made solo appearances with the Phoenix Symphony, Chicago String Ensemble, New World Symphony, and the Prometheus Chamber Orchestra. A graduate of the Juilliard School, he has performed chamber music extensively throughout New York.

In Sun Jang joined the San Francisco Symphony first violin section in 2011 and was previously a concertmaster with the New World Symphony. A top prizewinner at the International Henryk Szeryng Violin Competition, she has soloed with the New World Symphony, Puchon Philharmonic, and the Nanpa Festival Orchestra. She is a graduate of the Juilliard School and New England Conservatory.

Gina Cooper joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section in 1992, having served previously as a member of the Buffalo Philharmonic. A native of Ardsley, New York, she began her musical studies on piano and holds a master’s degree from the Yale School of Music.

Amos Yang joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2007 as Assistant Principal Cello and holds the Karel & Lida Urbanek Chair. He was previously a member of the Seattle Symphony and a member of the Maia String Quartet. Born and raised in San Francisco, he was a member of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra and San Francisco Boys Choir, and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Charles Chandler joined the San Francisco Symphony bass section in 1992 and previously served as associate principal bass of the Phoenix Symphony. The first member of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra to join the SF Symphony, he graduated from the Juilliard School.

Kelly Leon-Pearce joined the San Francisco Symphony second violin section in 1990 and previously served as a substitute with the New York Philharmonic and associate concertmaster of the Aspel Festival Orchestra. As a founding member of the Persichetti Quartet, she played the cycle of Persichetti quartets at Kennedy Center and a Bartók cycle at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She holds degrees from the Juilliard School.

David Goldblatt joined the San Francisco Symphony cello section in 1978 and holds the Christine & Pierre Lamond Second Century Chair, having previously played in the Pittsburgh Symphony. A graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, he has also performed with the Concerto Soloists of Philadelphia and Santa Fe Opera Orchestra. He is currently a coach for the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra.

June Choi Oh has performed with the New York Philharmonic’s chamber music series and at the United Nations, Chicago’s Dame Myra Hess Concert Series, Germany’s Kieller Schloss, Holland’s Stadsgehoorzall, Canada’s Victoria Music Festival, and Aspen Music Festival. As a soloist, she has appeared with the New Haven Symphony, Aspen Concert Orchestra, and Filarmonica de Jalisco. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Jessie Fellows is Assistant Principal Second Violin of the San Francisco Symphony and holds the Audrey Avis Aasen-Hull Chair. Prior to her appointment, she performed frequently with the St. Louis Symphony and New York Philharmonic. Born into a musical family, she began her studies at the age of three under the direction of her mother in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Olivia Chen joined the San Francisco Symphony’s second violin section at the beginning of the 2023–24 season and holds the Eucalyptus Foundation Second Century Chair. She served as concertmaster of the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra and has also performed with the New York String Orchestra at Carnegie Hall and with the Baltimore Symphony. Chen pursued her undergraduate studies at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, where she won the Marbury Violin Competition, the Melissa Tiller Violin Prize, and the Sidney Friedberg Prize.

Jeein Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony first violin section at the beginning of the 2024–25 season. She was previously a member of the Korean National Symphony and has been a substitute musician with the Chicago Symphony. As a soloist, she has performed with Praha Hradec Kralove Philharmonic, Yonsei University Orchestra, Prime Philharmonic Orchestra, JK Chamber Orchestra, and Northwest Sinfonietta. She studied at Yale School of Music, New England Conservatory, and Yonsei University. She has won top prizes at the Menuhin Competition, Seoul International Music Competition, and Northwest Sinfonietta Youth Competition.

Jane (Hyeon Jin) Cho joined the San Francisco Symphony second violin section in the 2025–26 season. She was a finalist in the 2022 International Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition and has performed as a substitute musician with the New York Philharmonic. She studied at the Royal College of Music in London and the Juilliard School.

Katarzyna Bryla joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section beginning with the 2022–23 season. She was born into a family of musicians and has earned more than two dozen awards in the United States, France, and her native Poland. In 2019 she became a coprincipal violist of Orchestra of St. Luke’s and has also been a member of the New York City Ballet Orchestra and the New York Pops.

Anne Richardson joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal Cello beginning in the 2024–25 season and holds the Peter & Jacqueline Hoefer Chair. She was most recently an academy fellow with the Bavarian Radio Symphony and has performed with the Verbier Festival Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and Pittsburgh Symphony. As a soloist, she has appeared with the Louisville Orchestra, Massapequa Philharmonic, Bryan Symphony Orchestra, and Juilliard Orchestra. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, she studied at the Juilliard School and the University of Michigan.

Sarah Chong joined the San Francisco Symphony cello section in September of this year and holds the Elizabeth C. Peters Cello Chair. A Bay Area native, she began her musical studies with Jihee Kim, and received her bachelor’s degree from Northwestern University. As an avid chamber musician, she has performed at the St. Paul String Quartet Competition, Fischoff Chamber Music Competition, the Meadowmount School, and Music@Menlo, and spent years under the guidance of the Dover Quartet.