In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, November 9, 2025, at 2:00pm

Musicians of the San Francisco Symphony

Erwin Schulhoff

Concertino for Flute, Viola, and Double Bass (1925)

Andante con moto

Furiant. Allegro furioso

Andante

Rondino. Allegro gaio

Yubeen Kim flute

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson viola

Bowen Ha bass

Maurice Ravel

Piano Trio in A minor (1914)

Modéré

Pantoum: Assez vif

Passacaille

Finale: Animé

David Chernyavsky violin

Amos Yang cello

Asya Gulua piano

Intermission

Ludwig van Beethoven

Septet in E-flat major, Opus 20 (1800)

Adagio–Allegro con brio

Adagio cantabile

Tempo di Menuetto

Tema con variazioni: Andante

Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace

Andante con moto alla Marcia–Presto

Matthew Griffith clarinet

Jessica Valeri horn

Joshua Elmore bassoon

Wyatt Underhill violin

Katarzyna Bryla viola

Anne Richardson cello

Daniel G. Smith bass

Program Notes

Concertino for Flute, Viola, and Double Bass

Erwin Schulhoff

Born: June 8, 1894, in Prague

Died: August 18, 1942, in Wültzburg Prison, Germany

Work Composed: 1925

He was a chameleon. Erwin Schulhoff started out as a late-Romantic student of Max Reger, but by the early 1920s he had become a devotee of the Second Viennese School, American jazz, and Dadaism. He composed a piano piece that anticipates John Cage’s 4’33” by consisting of only silence, but meticulously notated with a thicket of rests and deliberately nonsensical time signatures (such as 3/5), the whole directed to be played con espressione e sentimento ad libitum, sempre, sin al fine—i.e., with expression and free sentiment, always, until the end. He also wrote something called Sonata Erotica for solo female voice. No doubt such pieces were crazy fun for young radicals, but they didn’t sit well with the bourgeoisie. Schulhoff always teetered on the edge of financial and professional disaster.

The music of Schulhoff’s next period is considerably more approachable and comprehensible. From the mid-1920s through the early 1930s he wrote works that partake of Stravinskian neo-Classicism, laced through with Schoenbergian expressionism, jazz, and a certain broad Romanticism. During this time he was particularly involved with chamber music, producing a number of excellent string quartets and duo sonatas that still get heard once in a while. This is the time of the Concertino for Flute, Viola, and Double Bass of 1925, a four-movement work that seasons austere dignity with a distinctly cheeky vibe.

The opening Andante con moto starts out à la Erik Satie, all poker-faced white-key simplicity, but before long complexity arises and, with it, decidedly un-Satie-ish emotional heat. A gradual cooldown leads to a restatement of the opening materials, now marked senza espressione (without expression). The second-place Furiant is positively Bartókian, dancelike, jagged, and compelling. The quietly noble third movement requires the bass player to tune the E string lower to C. To conclude, a chipper Allegro combines a wry comedic sense with propulsive dance rhythms.

After the 1920s, Schulhoff became increasingly enmeshed in Marxist ideology and even attempted a musical setting of The Communist Manifesto. After his Jewish descent and radical politics led to his being blacklisted by the Nazi regime, he took refuge in Prague. In 1941 the Soviet Union approved his petition for citizenship, but the Nazis swept him up before he could leave. He died a year later from tuberculosis in a Bavarian prison, another victim of the Third Reich.

Piano Trio

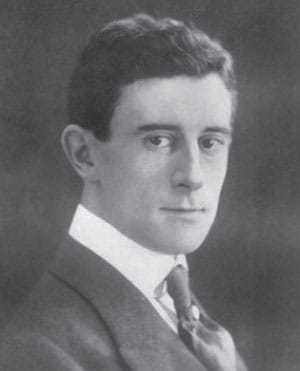

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1914

The piano trio might seem to be a slam dunk of an ensemble, a natural combination of sonorities that, like the string quartet, blend perfectly and are easy to balance. Composers have been writing piano trios for centuries, and one would think that’s with good reason. We might buy ourselves an elegantly-engineered Philips recording of the Beaux Arts Trio and revel in that luminous sound, so satisfying, so natural, so right.

But anyone who has played in a piano trio can testify it is an obstreperous beast, mulishly resistant to being corralled into civilized collaboration. A modern concert grand piano weighs a hundredfold more than a violin and cello together, and it’s a lot louder. There was a time when pianos were smaller and quieter, but that was long ago. The modern piano trio is akin to a 500-pound gorilla with a pair of canaries perched on its shoulders.

Maurice Ravel was all too aware of the genre’s shortcomings. When he took the plunge in his 1914 Piano Trio, he came up with an ingenious assortment of solutions. The violin might be placed high in its range, the cello correspondingly low, and the piano in the clear space between. Or that might be inverted, the right and left hands of the piano assigned the outer reaches of the keyboard while the two strings take up the middle. Another trick is to place both strings high in their respective ranges, which improves their audibility. Ravel also makes abundant use of alternate string techniques such as harmonics and pizzicato, all in the interest of proper acoustic détente between the three instruments.

The end result is a piano trio with an orchestral sheen about it, one of the most sonically satisfying examples of the genre ever written. However, all that technical magic would be little more than clever frippery without solid content, and here also the trio distinguishes itself. Its four movements are each meticulously constructed and filled with fascinating material, some of it drawn from Basque folk idioms (such as the zortziko rhythms of the first movement), and some of it reaching well beyond Ravel’s own time and place. Consider the second movement, which Ravel titles “Pantoum,” a verse form from Malaysia in which the second and fourth lines of each four-line stanza become the first and third lines of the next. Precisely how that translates to music isn’t altogether clear, but perhaps the movement’s alternating pair of themes reminded Ravel of the Malaysian verse form.

The trio evokes the past in its third movement, a passacaille, better known in its Italian spelling as passacaglia. It’s a variation form stemming back to the 16th century, in which a repeated bass line provides a static foundation for an unfolding series of variations. In a fine bit of structural integration, Ravel derived that bass line from the first theme of the Pantoum. The spectacular finale makes use of irregular meters (fives and sevens, no less) and brings the work to a close in a sunburst of major mode.

Septet in E-flat major, Opus 20

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1800

Never let it be said that Beethoven couldn’t trip the light fantastic when it suited him. Especially in his younger years, when he was a Viennese newbie and anxious to make good, Beethoven wrote a fair amount of lighthearted and entertaining music, all intended to accessorize the posh pastimes of the nobility and otherwise unconcerned with making a statement, advancing the art, or challenging the status quo. That was in keeping with the general tenor of life in Habsburg realms, where music played a pervasive and nearly omnipresent role. Much like today’s world with its inescapable background music, Beethoven’s Vienna was filled with small chamber groups that provided musical underpinning for just about everything and just about everywhere.

Serenades, divertimentos, cassations, and the like made up a substantial portion of the repertory. Loosely organized in multiple movements, they partook of the era’s signature forms (sonata, rondo, variation, and so forth) while maintaining a relatively casual approach to overall structure. Far less organized than symphonies, string quartets, or piano trios, they offered substantial value for the dollar—lots of not-too-difficult notes and a goodly mix of affects. What’s more, the best of them could stand comparison with their tonier concert brethren, such as the superb D-major serenade that Mozart retooled into his Haffner Symphony No. 35.

Beethoven knocked one out of the park with his Septet. On its premiere alongside the First Symphony at the Royal Imperial Court Theater on April 2, 1800, the sparkling Septet—a Serenade in all but name—was an instant and lasting hit. Over the years it came out in a potpourri of arrangements, including for solo piano, two guitars, piano duet, piano quartet, and a version by Beethoven himself as a trio for piano, cello, and either clarinet or violin. Such was its popularity that the piece began to haunt Beethoven. The problem wasn’t that Beethoven objected to the public’s esteem for the piece, or to the money that it earned. The issue was that he had evolved and the Septet hadn’t; he resented that it drew attention away from the extraordinary achievements of his maturity. “I wish somebody would burn it,” he sputtered in a moment of indignation.

It’s a considerably more adventuresome and forward-thinking composition than it might seem on the surface. Nobody had ever successfully combined so many wind instruments (clarinet, horn, and bassoon) with strings in a chamber texture, and nobody had ever given the winds so much independence. The three winds form a concertante group of their own, as do the four strings—which dispense with a second violin but include a double bass, which gives the sonority increased heft.

As was the custom during the Viennese Classical era, the Septet opens with a stately slow introduction before launching into the Allegro con brio proper, a superbly fashioned specimen of classic sonata-allegro form. A coda, or extension to the end of the movement—Beethoven just loved codas—shines a spotlight on the horn.

The exquisite Adagio cantabile is set in A-flat major, and thereby lies a topic of particular interest. Just as the key of A major seems to have elicited particularly lyrical writing from Mozart, ditto A-flat major for Beethoven. Consider some signature Beethoven A-flat moments, such as the second movements of both the Fifth Symphony and the Pathétique Piano Sonata. The Adagio cantabile of the Opus 20 Septet provides a splendid instance of Beethoven in A-flat major mode, lyrical and heartfelt, employing a shock modulation to relatively colorless C major before returning to the comforting glow of A-flat.

The Tempo di Menuetto is better known as the second movement of the “easy” Piano Sonata, Opus 49, no.2. However, the Opus 20 version differs substantially from its keyboard cousin, being more extended and offering contrasting episodes not found in the sonata.

The fourth movement consists of an elegant theme with five variations. In later life, Beethoven was to take variation form to unprecedented heights, but here he colors within the lines, as it were. Up next is a downright cute Scherzo that gives no hint of the volcanic fires to be ignited in Beethoven’s later scherzos. The cello gets the lead in the lovely, sweet-tempered Trio, a tune so ingratiating that it almost cries out for a sing-along.

The Septet ends in a substantial movement that begins with a somber funeral march. Frowns don’t last long in these sunny climes, and soon enough a joyous and downright whimsical Presto takes flight, another textbook-worthy example of Beethoven’s superlative handling of sonata form. Delightfully, the central development section includes an extended cadenza for solo violin. And course it ends with a coda. Beethoven wouldn’t be Beethoven without a coda.

—Scott Foglesong

About the Artists

Yubeen Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Flute in January 2024 and holds the Caroline H. Hume Chair. He was previously principal flute of the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra and has frequently played as guest principal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He won first prize at the 2022 ARD International Music Competition and 2015 Prague Spring International Music Competition and won multiple prizes at the 2014 Concours de Genève. He studied at the Lyon Conservatory, Paris Conservatory, and the Hanns Eisler School of Music Berlin.

Leonid Plashinov-Johnson joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section in 2022. Previously a member of the St. Louis Symphony, he is a laureate of multiple competitions, most recently the Primrose International Viola Competition, and has participated in the Yellow Barn, Ravinia, and AIMS festivals. Born in Russia, he graduated from New England Conservatory, where he won the concerto competition.

Bowen Ha joined the San Francisco Symphony bass section at the beginning of the 2024–25 season. He studied at the Shanghai Conservatory Middle School, Interlochen Arts Academy, and the Juilliard School. He has been a prizewinner at the Tang Rhyme Carnival International Double Bass Competition, Shanghai Conservatory Concerto Competition, Jacqueline Avent Concerto Competition of the Sewanee Summer Music Festival, Louisiana Bass Fest, International Concerto Competition of the Master Players Festival & School, and Juilliard Double Bass Concerto Competition.

David Chernyavsky joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2009. Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, he began violin studies at the age of six and at 11 gave his first solo recital. After winning prizes in competitions in Russia and France, he entered the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. After moving to the United States, he studied at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music and the Juilliard School. He has recorded several CDs with the Saint Petersburg Quartet and the Joel Rubin Klezmer Music Ensemble, and has released a solo CD, Klezmer Violin.

Amos Yang joined the San Francisco Symphony in 2007 as Assistant Principal Cello and holds the Karel & Lida Urbanek Chair. He was previously a member of the Seattle Symphony and a member of the Maia String Quartet. Born and raised in San Francisco, he was a member of the SF Symphony Youth Orchestra and San Francisco Boys Choir, and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Asya Gulua received her initial musical training at the Gnessin School of Music in Moscow. In 1996 she immigrated to the United States and enrolled at the Interlochen Arts Academy. She holds degrees from the Juilliard School, Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, and the University of Oregon. She lives in Salem, Oregon, where she works for the Oregon Symphony Association, teaches private students, and collaborates with musicians and composers locally and nationally.

Matthew Griffith joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal and E-flat Clarinet at the beginning of the 2022–23 season. He previously served as acting assistant principal clarinet with the North Carolina Symphony and the Nashville Symphony and was a member of TŌN (The Orchestra Now) at Bard College. He has performed as guest soloist with the Boston Pops, Milwaukee Symphony, Ocean City Pops, Eastern Connecticut Symphony, United States Army Field Band, and “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band.

Jessica Valeri joined the San Francisco Symphony horn section in 2008. Prior to her appointment, she was a member of the St. Louis Symphony, Colorado Symphony, Grant Park Orchestra, and Milwaukee Ballet Orchestra. She has also performed with the Milwaukee Symphony, Richmond Symphony, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the International Contemporary Ensemble, and participated in the Grand Teton Music Festival, Lakes Area Music Festival, and Mainly Mozart.

Joshua Elmore joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Bassoon in March 2025. He previously served as principal of the Fort Worth Symphony and has also performed with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, and Chineke! Orchestra. In 2022, he served as principal bassoon for the Gateways Festival Orchestra’s historic Carnegie Hall debut, playing with the first all–African American orchestra to appear at the venue. He studied at the Juilliard School and Colburn School, and was a fellow at the Tanglewood Music Center.

Wyatt Underhill joined the San Francisco Symphony as Assistant Concertmaster in 2018 and holds the 75th Anniversary Chair. He was previously assistant concertmaster of the Baltimore Symphony, substitute concertmaster with the New Haven Symphony, and associate concertmaster of Symphony in C. He was the founding first violinist of the Blue Hill String Quartet and was a top prizewinner in the Irving M. Klein International Competition for Strings.

Katarzyna Bryla joined the San Francisco Symphony viola section beginning with the 2022–23 season. She was born into a family of musicians and has earned more than two dozen awards in the United States, France, and her native Poland. In 2019 she became a coprincipal violist of Orchestra of St. Luke’s and has also been a member of the New York City Ballet Orchestra and the New York Pops.

Anne Richardson joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal Cello beginning in the 2024–25 season and holds the Peter & Jacqueline Hoefer Chair. She was most recently an academy fellow with the Bavarian Radio Symphony and has performed with the Verbier Festival Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and Pittsburgh Symphony. As a soloist, she has appeared with the Louisville Orchestra, Massapequa Philharmonic, Bryan Symphony Orchestra, and Juilliard Orchestra. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, she studied at the Juilliard School and the University of Michigan.

Daniel G. Smith was appointed Associate Principal Bass of the San Francisco Symphony in 2017. He previously served as principal bass of the Santa Barbara Symphony, and he was a member of the San Diego Symphony. He has served as guest principal and associate principal bass with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and guest principal of the Lakes Area Music Festival in Brainerd, Minnesota. He received his Bachelor of Music from Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music.