In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, May 29, 2025, at 2:00pm

Friday, May 30, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, June 1, 2025, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Opus 60 (1806)

Adagio–Allegro vivace

Adagio

Allegro vivace

Allegro ma non troppo

Intermission

Ludwig van Beethoven

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 61 (1806)

Allegro ma non troppo

Larghetto

Rondo: Allegro

Hilary Hahn

These concerts, a part of The Barbro and Bernard Osher Masterworks Series, are made possible by a generous gift from Barbro and Bernard Osher.

Thursday matinee concerts are endowed by a gift in memory of Rhoda Goldman.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half of the program, Hilary Hahn joins for Beethoven’s only Violin Concerto. It begins, unlike any concerto before it, with five soft taps on the timpani. Then the woodwinds sing a serene melody, only to be rudely interrupted by the violins’ strange mimicry of the timpani’s opening knocks. This rhythmic motif recurs throughout the work, inspiring dozens of variations.

Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Opus 60

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1806

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1916. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—January 2017. Lionel Bringuier conducted.

Instrumentation: flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony is probably the least frequently performed of his nine symphonies, which reflects less on the work itself than on the other eight, or at least a handful of them. Viewed in the context of Beethoven’s corpus, listeners may be tempted to focus on what the Fourth Symphony is not, rather than on what it is.

What it is not, most immediately, is Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, those two punch-packing, jaw-dropping exercises in superhuman grandeur and titanic power. Robert Schumann poetically captured the Fourth’s relationship to its neighbors when he called it “a slender Grecian maiden between two Nordic giants.” Berlioz viewed it as a return to an earlier sound world. “Here,” he wrote, “Beethoven entirely abandons ode and elegy, in order to return to the less elevated and less somber, but not less difficult, style of the Second Symphony. The general character of this score is either lively, alert, and gay or of a celestial sweetness.”

Beethoven was pressed for cash when he wrote his Fourth Symphony, trying to cover his own expenses as well as debts piled up by his relatives. Although he was accustomed to renting modest residences outside Vienna in which to spend his summers, he decided to forego that pleasure in 1806, though at the end of summer he headed with his patron Prince Lichnowsky to Silesia. During that journey, he and the prince paid a visit to Count Franz von Oppersdorff, who maintained a small private orchestra. Oppersdorff was so enthusiastic about music that he required everyone on his staff to play an instrument, and he was delighted to entertain Lichnowsky and Beethoven by having his musicians perform the composer’s Second Symphony. Musicological opinion used to hold that the count offered to commission a symphony, and Beethoven leapt at the chance. It seems more likely, however, that Beethoven had already completed the Fourth and that Oppersdorff offered to purchase rights to it. But if the count’s orchestra played this music before its Vienna premiere, we have no record of such a performance. In any case, when Beethoven offered this piece to his publishers on September 3, he claimed it was essentially finished, and it seems that he wrote it not as work for hire, but simply because he wanted to.

Whatever its genesis, the Fourth Symphony seems to have given its composer little trouble. Few preliminary sketches exist, and those that do give no evidence of the agonizing experimentation and reworking often apparent in Beethoven’s drafts.

The Music

Following in the steps of Haydn (who in 1806 was still active but emphatically retired), Beethoven opens his Fourth Symphony with a hushed, introspective introduction, harmonically evasive but emphasizing the minor mode. A listener encountering the piece for the first time would have every reason to expect that a work of tension, suspense, and mystery lay in store. But in an eight-measure passage—fortissimo and with the texture expanded to include the brilliance of trumpets and timpani—that embraces the end of the Adagio and the beginning of the Allegro vivace, a rapidly ascending scale figure cuts through the darkness and breaks apart into ever smaller fragments, not unlike fireworks that fragment into sparkling shards. And suddenly we realize that the orchestra has embarked on what will be a thoroughly playful fast movement. It unrolls according to a succinct Classical method, with a “proper” second subject being introduced through a perky conversation among the bassoon, oboe, and flute. But we can rely on Beethoven to inject some unusual characterization. The movement’s development section boasts an irresistible overlay of a new song-like melody in counterpoint above (or below, or around) the entries of the movement’s main theme. What’s more, the whole section spends a fair amount of time pretending that it is going to resolve to B-natural—so near to, but yet so far from, the true destination of B-flat, which is reached via a crescendo that grows out of a sudden hush.

The second movement also recalls Haydn through a recurrent rhythmic pattern, rather along the lines of the accompanying figures that pop up in that composer’s Symphonies Nos. 22 (The Philosopher) and 101 (The Clock). This pattern acts as both support of and foil to the tender melody that unrolls above it. At the middle of the movement stands an episode that the distinguished musical analyst Donald Francis Tovey called “one of the most imaginative passages anywhere in Beethoven.” Its unanticipated movement from an angry minor-key transformation of the principal theme to a delicate duet for violins alone is indeed extraordinary. The slow movement concludes with a coda in which the main theme is fragmented and distributed throughout the orchestra; and at the very end, the timpani intone the rhythmic underpinning of the opening, which, in retrospect, sounds as if it could have been a drumbeat all along.

In his third movement, Beethoven has already left the spirit of the Classical minuet in the dust, replacing it definitively with the high-energy of the scherzo. Duple-time figures compete with the underlying triple-time pulse to yield dramatic cross-rhythms. An unaccustomed return to the trio for a second go-round expands the minuet’s standard three-part structure into a five-part form. (Beethoven apparently liked the balance achieved through this pattern, as he turned to it again in his sixth and seventh symphonies.)

The scurrying opening theme of the last movement announces the perpetual-motion character that will pervade the finale. Before he reaches the end, the composer works in a last laugh or two. The development section keeps the audience wondering where everything is heading. Where it’s heading is, of course, where the movement’s main theme is expected to return for its concluding argument; but when we arrive there, the theme is stated not by the full orchestra but rather by a single bassoon, chortling a bit bumptiously through the flurry of rapid-fire 16th notes. The orchestra swoops in to pick up the tune and nearly makes it to the end before threatening to break down in exhaustion. A few instruments manage to puff out the theme pianissimo at half its tempo—and then, with a final surge of energy and a few boisterous chords, Beethoven’s Fourth crosses the finish line buoyantly.

—James M. Keller

A version of this note originally appeared in the program book of the New York Philharmonic and is reprinted with permission.

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 61

Ludwig van Beethoven

Work Composed: 1806

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1914. Henry Hadley conducted with Fritz Kreisler as soloist. Most recent—November 2017. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Vivane Hagner as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 40 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven had studied the violin as a young man in Bonn and had spent a stint as an orchestral violist before moving to Vienna to seek his fortune as a pianist and composer. In the early 1790s he had tried his hand at a Violin Concerto in C major, which he left incomplete, and around the turn of the century he penned two charming, single-movement Romances for violin and orchestra. He was also actively composing chamber music with violin, and by the time he got around to writing his Violin Concerto he had completed nine of his ten violin sonatas. He arrived at the concerto project with considerable mastery of the instrument for which he was writing and awareness of the tradition into which his new work would be placed.

The violinist Beethoven chose as midwife for his concerto was Franz Clement (1780–1842), whom he had met in 1794 when the Vienna native was a 13-year-old prodigy on the way to becoming one of Europe’s most acclaimed virtuosos. Clement went on to become a fixture on the concert scene in London, and from 1802 to 1811 he served as leader of the Theater an der Wien’s orchestra. Clement would achieve success elsewhere as a conductor and violinist, with critics numbering firmness of tone, elegant clarity, tender expressiveness, spot-on intonation, and deft bowing among his characteristic strengths. He published several compositions, too, including a D-major Violin Concerto of his own, but his career concluded badly, and financial mismanagement led him to an ignominious and impecunious end. But in 1806 he was flying high, and Beethoven was delighted to work with him. Clement already had experience making sense of Beethoven’s sometimes audacious style, which he had encountered as one of the first conductors to lead the Eroica Symphony. “Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement,” Beethoven inscribed at the top of the concerto’s manuscript—“Concerto for Clement, out of Compassion.”

Under such circumstances, the concerto’s success would have seemed secure. But something went wrong. Anton Schindler, the sometimes credible chronicler of Beethoven’s life, recalled in 1840: “The concerto enjoyed no great success. When it was repeated the following year it was more favorably received, but Beethoven decided to rewrite it as a piano concerto. As such, however, it was totally ignored: Violinists and pianists alike rejected the work as unrewarding (a fate it has shared with almost all of Beethoven’s works until the present time). The violinists even complained that it was unplayable, for they shrank from the frequent use of the upper positions.” It is true that Beethoven requires his soloist to spend a great deal of time in the stratosphere and that by the end of the concerto not much rosin will have been rubbed off on the lowest of the instrument’s four strings. But apart from that, the concerto does not harbor an inordinate amount of strictly technical challenges. Double stops scarcely appear and “advanced” modes of attack, such as pizzicato or spiccato, don’t play much of a part here. Instead, Beethoven offers streams of swirling figuration, much of it elaborating material that has previously been proposed by the orchestra, all of it precisely the sort of writing to which Clement was apparently born.

Carl Czerny, another member of Beethoven’s circle, said that the composer had written the concerto quickly and had only managed to complete it two days before the premiere, with the result that Clement had no choice but to sight-read the solo part at the performance. But the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of Leipzig ran a news item that suggests Clement acquitted himself with honor under the circumstances: “To the admirers of Beethoven’s muse it may be of interest that this composer has written a violin concerto—the first, so far as we know—which the beloved local violinist Klement [sic], in the concert given for his benefit, played with his usual elegance and luster.”

Schindler was right in describing the neglect this concerto suffered in its early years. The work failed to whip up much audience enthusiasm until 1844, when the Philharmonic Society of London programmed it with Felix Mendelssohn conducting and Joseph Joachim as soloist. For the lion’s share of the breakthrough we have Joachim to thank—and the astonishment the London public felt, witnessing such masterful achievement from a soloist who was only 12 years old. Joachim kept the concerto in his repertory, and the cadenzas he wrote for it have long been accepted as the standard against which others are judged. The Beethoven Violin Concerto that Joachim played, by the way, and that every violinist has played since, was not quite the same Beethoven Violin Concerto that Clement premiered. Due to the apparent haste of composition, some of the solo notation was on the sketchy side, and before he published the piece Beethoven subjected the entire concerto to severe revision in both the solo and the orchestral parts.

Though a listener can expect that a new work will hold its share of surprises, nobody at the premiere could have anticipated the first sounds of this concerto: five quiet beats on the timpani, followed by a full-fledged theme from the wind choir and another five timpani beats. Then, for their entrance, the orchestral strings mimic the kettledrum’s rhythm. That motif will be present often in the first movement.

The orchestra goes about introducing the movement’s principal themes. The soloist enters with a page of filigree spun across three and a half octaves, which leads to the violin’s first truly “thematic” material, a passage that exemplifies Beethoven’s penchant for using the solo part as a sort of decorative rumination on material presented more squarely by the orchestral forces. This is a long, firmly constructed movement.

The slow movement unrolls as a set of variations on a supremely poised melody that may remind some listeners of a chorale. The strings install mutes for the beginning of the movement, and it is they who first present the melody, followed by variations featuring clarinet, bassoon, and then the full orchestra. The violin inserts an exquisite passage before the fourth variation begins. Here the theme resides in the orchestral strings, playing piano and pizzicato, with the soloist providing contrapuntal elaboration above. The result suggests that the violinist is improvising, though of course Beethoven has plotted everything carefully in this transcendent movement.

The first movement is grandly awesome. The second is poignant and heartfelt. The finale, following without a break, is a rollicking, mischievous Rondo designed for fun and bravura. Although Beethoven failed to indicate a specific tempo marking, there’s no question that he intended it to be quick.

—J.M.K.

A version of this note originally appeared in the program book of the New York Philharmonic and is reprinted with permission.

About the Artists

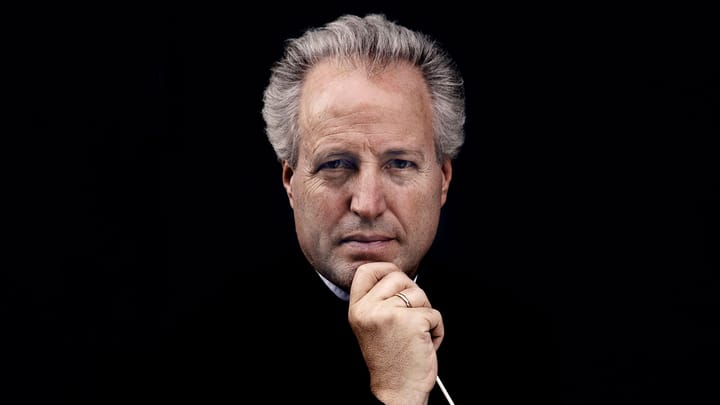

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

Hilary Hahn

Three-time Grammy Award–winning violinist Hilary Hahn melds expressive musicality and technical expertise with a diverse repertoire guided by artistic curiosity. She is a prolific recording artist and commissioner of new works, and her 23 feature recordings have received numerous international prizes and acclaim. She is currently a visiting professor at the Royal Academy of Music, and has been an artist in residence with the Chicago Symphony and New York Philharmonic, a visiting artist at the Juilliard School, and a curating artist for the Dortmund Festival. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in October 1999 as a Shenson Young Artist.

Hahn has related to her fans naturally from the very beginning of her career. Her social media initiative, #100daysofpractice, has transformed practice into a community-building celebration of artistic development. Since Hahn created the hashtag in 2017, fellow performers and students have contributed more than one million posts. A former Suzuki student, she released new recordings of the first three books of the Suzuki Violin School in 2020. In 2019, she released a book of sheet music, In 27 Pieces: the Hilary Hahn Encores, which includes her own fingerings and bowings and performance notes for each work.

In recent seasons, Hahn has received the Avery Fisher Prize, was named Musical America’s 2023 “Artist of the Year,” received the 2021 Herbert von Karajan Award, and was awarded the 11th Annual Glashütte Original Music Festival Award, which she donated to the Philadelphia-based music education nonprofit Project 440. Hahn was the 2022 Chubb Fellow at Yale University’s Timothy Dwight College; she also holds honorary doctorates from Middlebury College and Ball State University, where there are three scholarships in her name.