In This Program

- Welcome

- Becoming Beethoven: Mozart, Beethoven, and the anxiety of influence

- Four Questions For Pianist Mao Fujita

- Community Connections

- Meet the SF Symphony Musicians

- Print Edition

Welcome

The San Francisco Symphony offers a space to experience inventive projects that embrace curiosity. This month, several artists take the stage in performances that invite us to engage with music in new ways.

In her Great Performers Series recital, Nicola Benedetti reimagines violin showpieces for an intimate “café-style” ensemble of violin, cello, guitar, and accordion. In reconnecting with music from her student days, she hopes to bring audiences “closer to music, closer to us, and closer to each other.”

Violinist Alexi Kenney’s SoundBox performances reflect his adventurous sense of programming while showcasing the artistry of our San Francisco Symphony musicians in thrilling and unconventional contexts.

Mozart’s Requiem is deeply personal for conductor Manfred Honeck, who is inspired by its “message of hope and comfort.” His unique presentation brings together Mozart’s music and letters with the spiritual traditions of Mozart’s time in a fresh approach to the composer’s final work.

Each of these performances is a reminder of how great art can take us to new places, provoke deeper thought, and bring us closer together. We’re excited to keep expanding what a San Francisco Symphony concert can be for you.

Matthew Spivey

Chief Executive Officer, San Francisco Symphony

Becoming Beethoven

Mozart, Beethoven, and the anxiety of influence • By René Spencer Saller

AFTER HEARING MOZART’S C-MINOR PIANO CONCERTO for the first time, Beethoven supposedly exclaimed to a colleague, “We shall never be able to do anything like that!”

For many composers—and artists in general—the line between legacy and burden is blurry at best. What happens when a creative influence doesn’t inspire so much as inhibit? Harold Bloom wrote two books on the topic, The Anxiety of Influence and The Map of Misreading. In them, the late literary theorist argued that the strongest poets are the ones who misread their fearsome forebears, usually as a subconscious defense mechanism against the ego-corroding force of influence. This productive misunderstanding helps the strongest, most original poets protect their developing egos and reclaim their creative mojo. Replace “poet” with “composer,” and Bloom’s theory works equally well.

Bloom reframes the issue of influence in Freudian terms, but you don’t need to review your Psych 101 notes to understand the related concept of ambivalence. Most of us know what it feels like to admire someone who makes us feel inferior by comparison—for me, if you must know, it’s Jan Swafford and the late Michael Steinberg—so we get why the ego might develop defense strategies against this profuse admiration. Kill your idols, as the ’80s punk slogan goes. It’s never quite that easy, alas. Your idols might be dead already.

As a teenager in his native Bonn, Beethoven was urged by his patron Count Waldstein to make a pilgrimage to Vienna and “receive the spirit of Mozart at Haydn’s hands.” Although he dutifully complied, the pressure made him queasy. On the one hand, he wanted to enter the pantheon; on the other hand, he needed to assert his independence. Just as Beethoven’s looming presence would both inspire and inhibit his successors—“Who can do anything after Beethoven?” Schubert famously griped—Mozart provoked a similar ambivalence in Beethoven.

Although Beethoven pored over Mozart’s scores from early adolescence and would later study with Mozart’s mentor and champion, Joseph Haydn, no one knows whether Beethoven and Mozart actually met. Swafford, who wrote comprehensive biographies of both composers, believes that it’s possible, although most of their reported exchanges seem to be fabricated. Beethoven did take in some Mozart performances, both in Bonn and Vienna. But regardless of whether theirs was a literal or a purely parasocial relationship, the connection started during Beethoven’s childhood. Beethoven’s drunken wastrel of a father tried to transform himself from a small-time music instructor into Leopold Mozart, the consummate stage dad, while positioning the young Beethoven, who was about 14 years Mozart’s junior, as the hot new talent. Given expert guidance and instruction, the child might have been capable of taking on the prodigy circuit, but his father lacked Leopold’s entrepreneurial drive and discipline. Beethoven’s father seldom saw anything through, aside from the brutal beatings that he regularly inflicted on his children. He was a burden, not a provider.

Beethoven might not have been swanning around the continent and hobnobbing with royalty as a child and teenager, but he understood that he needed to sound as Beethovenian as Mozart sounded Mozartian. Paradoxically, he became most distinctively himself when he learned so much Mozart that he could channel him almost intuitively, improvise on his themes, lift his harmonic shifts, quote lines from his operas—the one form where Beethoven comes up short. (Don’t fight me, Fidelio fans: I’m confident that Beethoven, who adored Die Zauberflöte, would agree.)

If the Bloomian or Freudian interpretation feels needlessly combative to you, you’re not alone. Some of us perceive creative influence as a source of joy, a way to converse and commune with formative paternal and (not that Bloom ever fully acknowledged them) maternal figures. Often the dynamic of influence seems less like a competition designed to vanquish and subjugate the problematic precursor and more like a posthumous collaboration. The most loving response to a work of art, or a sunset, or a child, or an ailing parent, is close attention. When we focus fully on another human being or on something created by another human being—large language models need not apply!—we escape the constraints of consciousness and time. Often, as Beethoven found in Mozart, we discover an ally, not an authority figure or a rival. Instead of punishment and endless one-upmanship, this form of influence offers sustenance and support.

We don’t need to kill our idols, or even maim or disfigure them. We can follow the lead of Beethoven, who undercut the occasional snippy comment—he allegedly told his student Carl Czerny that Mozart’s playing was fine but choppy, lacking any legato—with the only tribute he cared about, the musical kind. His many quotations from Mozart scores aren’t the main reason that music writers invariably refer to Beethoven’s Mozartian tendencies. Beethoven immersed himself so completely in Mozart’s sound world that he could recreate it in his own singular language. This degree of devotion is best described as love.

On a sketch in C minor from 1790, the year before Mozart’s premature death, Beethoven dashed off a note, to himself and to posterity: “This entire passage has been [inadvertently] stolen from the Mozart Symphony in C [“Linz”].” He then made a few minor adjustments to the passage before signing it “Beethoven himself.”

Whether Beethoven “misread” Mozart to enact his Mozartian magic is immaterial. For almost his entire life he was pitted against his near-contemporary, and people continued to compare them long after their respective deaths. We compulsively play the same dumb rhetorical games with different artificial binaries—Beatles vs. Stones, Kendrick vs. Drake, boxers vs. briefs—as if a fondness for one thing precludes appreciation of the other. Declaring our allegiance to Mozart instead of Beethoven, or vice versa, narrows our range of experience and deprives us of pleasure.

In his critical reappraisal of Beethoven, the late musicologist Richard Taruskin lamented what he called the “newly sacralized view of art” and blamed Beethoven for turning concert halls into museums or temples. He was right to question the Romantic myths surrounding Beethoven’s life and career, the overwhelming tendency to present his struggles as heroic, his suffering as unique and transcendent. But Taruskin also felt that Beethoven’s influence stifled his successors more than it freed them to pursue their own creative paths. Through no fault of his own, the fallible human being became a godlike authority, a scary dad, a mentor-cum-tormentor of future generations.

If you were expecting a sassy Taruskinesque takedown, sorry to disappoint. Although we do Mozart and Beethoven no favors when we turn them into distant unknowable gods, we also gain nothing by trashing them. Besides, if there’s anything sillier than worshiping the dead, it’s fighting the dead, or even defending them. The best will survive our blather. After all, they survived one another.

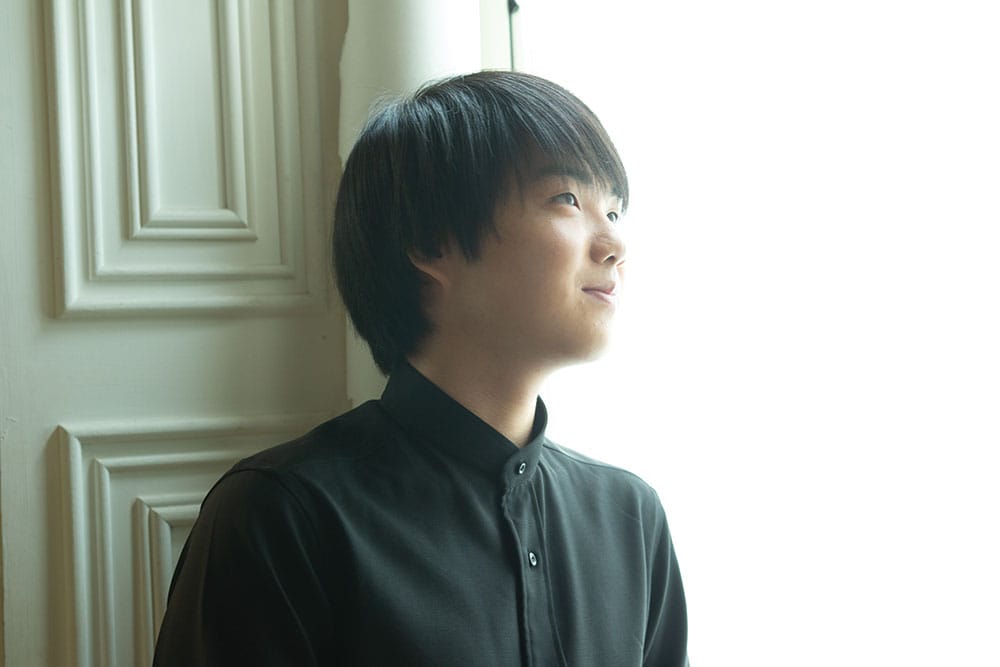

Four Questions For Pianist Mao Fujita

Tell us a little about what you’re playing in your Spotlight Series recital.

In this recital, I will play pieces that Beethoven, Berg, and Brahms wrote when they were still young. We know how great they all became later, but even in these early works you can already feel the strong energy that shaped their future music. In Beethoven’s Opus 2, no.1, the famous “Fate” motif already appears. Berg’s Twelve Variations were written when he had just started studying with Schoenberg, and you can hear his early but very beautiful harmonic ideas. And in Brahms’s First Sonata, you can hear a motif that seems inspired by Beethoven’s Hammerklavier [Sonata], but it also has Brahms’s own rhapsodic style. These works are full of character and are very exciting to perform.

What inspired you to pursue a career in classical music?

From a very young age, classical music was simply a natural part of my life. Just like brushing my teeth, eating meals, or going to sleep, making music was something I did every day without question. While my friends were playing together or enjoying games, I was practicing the piano. It was always a joy, and it is still so.

What’s your routine like on concert days?

The concert requires an intense amount of concentration, so I try to sleep as much as possible before performing. When I go on stage, I play with the feeling that I am giving my whole life to the music.

What influences your creativity and artistic expression?

I don’t have many hobbies outside of music, but I really enjoy visiting museums and seeing great works of art. I also love reading books. You know, manga is big in Japan, which is where I was born and grew up, but it’s not enough for me. I prefer reading texts and creating the images in my own mind; imagining the scenes for myself helps nurture my inspiration and creativity.

Community Connections

Students Rising Above

Only 26% of first-generation students graduate with a college degree, compared to 60% of students whose parents attended college. Students Rising Above (SRA) is determined to change the odds. SRA understands the rewards and obstacles students face in defying expectations, and how their success can lift up entire communities. Since 1998, SRA has helped craft, nurture, and navigate college experiences that lead to meaningful careers.

Students Rising Above empowers students facing systemic barriers to define and find success through education, career, and in life, believing that every student who aspires to go to college should have the opportunity to thrive in higher education and enter economically mobile careers. By 2035, SRA aims to support 2,500 students every year to intentionally use their college experience to unlock more opportunities.

Enlisting comprehensive support, personal relationships, and career guidance, SRA has become one of the most successful college completion programs in the nation, believing that every student who aspires to go to college should have the opportunity to thrive in higher education and enter economically mobile careers. Join SRA as they redefine what’s possible for the next generation.

For more information about Students Rising Above, visit studentsrisingabove.org.

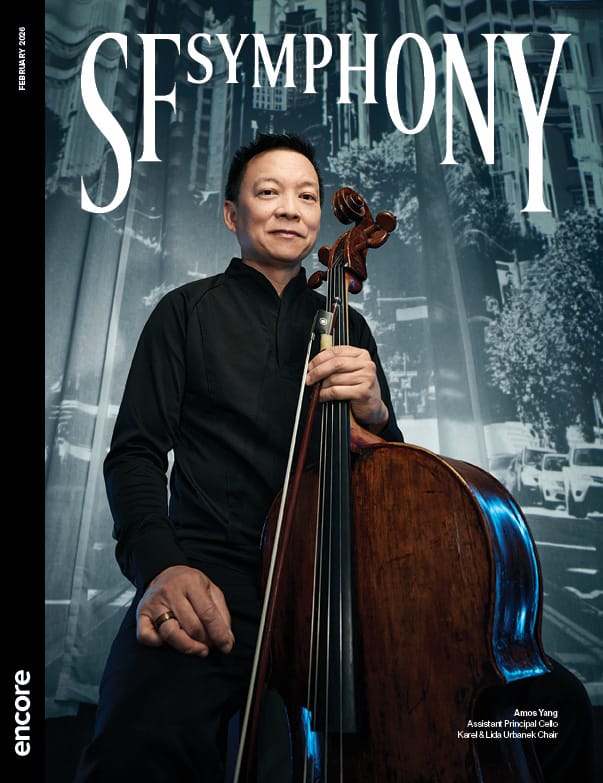

Meet the Musicians

Amos Yang • Assistant Principal Cello, Karel & Lida Urbanek Chair

A San Francisco native, Amos Yang joined the SF Symphony in 2007.

What was your first concert with the SF Symphony?

It was a European festivals tour in 2007, which was already scary, and we were playing Shostakovich Five, Tchaikovsky’s First Symphony, and Mahler Seven. I was hired as Assistant Principal, but sat at the first stand as Associate Principal for that tour.

How did you begin playing the cello?

I’m so grateful to have been born and raised here in San Francisco. I began cello studies at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music with a now legendary cello guru, Irene Sharp, but we were her first crop of kids. In 1981 I joined the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra in its inaugural year as an 11-year-old. I was promptly kicked out of the YO by Jill Brindel, a future colleague of mine, but I auditioned back in with the understanding I would try a little harder the second time!

What were your next steps in becoming a professional musician?

After leaving San Francisco, I studied at both the Juilliard School and the Eastman School of Music. My important teachers were Channing Robbins, Paul Katz, Steve Doane, and Joel Krosnick—formerly of the Juilliard String Quartet. I also studied abroad in London for one year and then joined a string quartet that had a residency at the Peabody Conservatory and later the University of Iowa. After that, I played in the Seattle Symphony for several years.

What kind of cello do you play?

I play mainly on a Carlo Giuseppe Testore cello from the 1690s, owned by the Symphony. It’s a wonderful “old man” made in Milan, and I’m one of maybe 20 people or so that have put their voice into this instrument. It has such amazing layers and a warmth that is just fantastic. The Symphony acquired it for me, they sent me out to Chicago and put me in a room with seven instruments and said, “pick one of these, Amos.” But I didn’t trust myself, so I brought three consultants: my brother, who’s a violinist in the Rochester Phil, and two colleagues from the Chicago Symphony who play on very old instruments. I also own a cello made by Robert Brewer Young, who is a friend, and it’s a new instrument I hope in 300 years will sound equally as good as the Testore.

What about your bows?

I own a bow by Nikolaus Kittel who was a great Russian maker in the 1800s. For many years we had the world’s Kittel expert, Kenway Lee, here in San Francisco, so many of us in the Symphony and in the Bay Area have bows by this unique and rare maker.

What other musical activities do you pursue?

I love teaching, it’s one of the things I feel responsible for. I draw from all the wonderful things Irene Sharp gave me, and my coaches at Tanglewood gave me, and my teachers from Juilliard gave me, and try to keep the tradition alive. I also love chamber music—it’s nice to play smaller scale concerts and repertoire so that your voice is highlighted in a different way.

What do you enjoy besides music?

Family time is really important to me, even though we’re empty nesters. We recently sent our youngest off to UC Santa Barbara. And I love biking—if you’re out late in San Francisco, you might see me on Twin Peaks or in Golden Gate Park because I like riding at night.

Print Edition