In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, September 18, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, September 19, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, September 20, 2025, at 7:30pm

Preconcert Talk with David H. Miller, UC Berkeley Department of Music

On stage at 6:30pm before each performance

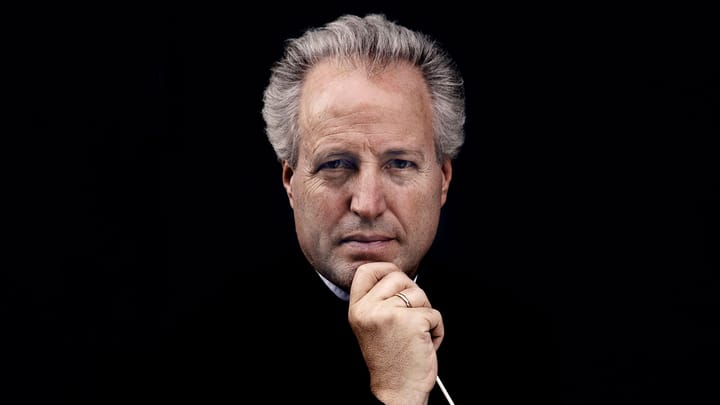

James Gaffigan conducting

Carlos Simon

The Block (2018)

George Gershwin

Piano Concerto in F (1925)

Allegro

Adagio

Finale: Allegro agitato

Hélène Grimaud

Intermission

George Gershwin

An American in Paris (1928)

Duke Ellington

(orch. Luther Henderson)

Harlem (1950)

Preconcert talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

In between are two works by George Gershwin: first pianist Hélène Grimaud performs the Concerto in F, which picks up where Rhapsody in Blue left off, weaving jazz into a more extended, three-movement classical form. Then An American in Paris, where the listener is led to imagine swinging down the Champs-Elysees, getting a little drunk in a café, feeling homesick, and finally enjoying the French nightlife with a revived spirit.

The Block

Carlos Simon

Born: April 13, 1986, in Washington, DC

Work Composed: 2018

SF Symphony Performances: First—July 2021. Edwin Outwater conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (suspended cymbal, bell tree, tubular bells, egg shakers, tambourine, drum set, glockenspiel, vibraphone, and marimba), harp, piano, and strings

Duration: About 6 minutes

Carlos Simon grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, and his distinctly American voice carries influences of jazz, gospel, and neo-Romanticism. He comes from a multigenerational lineage of preachers, and his father wanted him to follow that path, “But I always tell him, ‘Music is my pulpit. That’s where I preach,’” the composer reflected for The Washington Post. He is also a product of his classical training, having earned degrees at Georgia State University and Morehouse College, as well as a doctorate from the University of Michigan.

Simon is the Kennedy Center’s composer in residence, the inaugural Boston Symphony Orchestra Composer Chair, and was nominated for a 2023 Grammy Award for his album Requiem for the Enslaved. He was also a recipient of the 2021 Sphinx Medal of Excellence, the highest honor bestowed by the Sphinx Organization to recognize extraordinary classical Black and Latinx musicians, and was named a Sundance/Time Warner Composer Fellow for his work in film.

Last season saw premiere performances of Simon’s works with the National Symphony, Boston Symphony, BBC Symphony for the Last Night of the Proms, Jacksonville Symphony, Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Carnegie Hall for the National Youth Orchestra of the USA, and the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Gustavo Dudamel. In August 2024, Simon released his first full-length orchestral album, Four Symphonic Works, which opens with The Block performed by the National Symphony, conducted by Gianandrea Noseda.

Simon is also a dedicated curator and educator who has recently programmed concerts for the Atlanta Symphony, Boston Chamber Players, Tanglewood Festival for Contemporary Music, and the Kennedy Center. He curated and arranged Coltrane: Legacy for Orchestra, co-commissioned by TO Live (for the Toronto Symphony) and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, in partnership with the Coltrane Estate. He has served as a member of the music faculty at Spelman College and Morehouse College in Atlanta and now serves on the faculty of Georgetown University.

The Music

The Block draws inspiration from a six-painting series of the same title by Romare Bearden (1911–88), an artist whose work chronicled the Black culture of Harlem. Painted in 1971, the series is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Simon explains:

The Block is comprised of six paintings that highlight different buildings (church, barbershop, nightclub, etc.) in Harlem on one block. Bearden’s paintings incorporate various mediums including watercolors, graphite, and metallic papers. In the same way, this musical piece explores various musical textures which highlight the vibrant scenery and energy that a block on Harlem or any urban city exhibits.

Simon’s language is strikingly visual, evoking the cityscape in its first few gestures. After an opening rumble of orchestral percussion calls us to attention, a piccolo awakens atop shimmering strings and a gentle jazz kit. Swelling trumpets usher us into a robust landscape, full of darting and responsive interplay between the sections.

After a lyrical theme carried first by the violins and then by the brass, the piccolo recurs as a transitional element. The brass pick up the mantle once more in an ebullient final section and carry the piece towards its declamatory final statement.

Piano Concerto in F

George Gershwin

Born: September 26, 1898, in Brooklyn, New York

Died: July 11, 1937, in Hollywood, California

Work Composed: 1925

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1937. Pierre Monteux conducted with George Gershwin as soloist. Most recent—February 2023. Edwin Outwater conducted with Conrad Tao as soloist.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, snare drum, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

In his time, there were few spheres of American musical culture in which George Gershwin was not influential. A prominent composer of concert music, popular music, and musical theater alike during the early decades of the 20th century, Gershwin was consistent in his embrace of jazz tropes within divergent genres (his earliest student composition, according to biographer Howard Pollack, was a jazzy reworking of Robert Schumann’s “Träumerei” from Kinderszenen).

The son of Ukrainian and Russian Jewish immigrants, a 15-year-old Gershwin found work as a “song plugger” on Tin Pan Alley, where, in the words of historian Ulf Lindberg, “vernacular African-American impact coming from ragtime. . . the blues, and jazz,” mingled with “input from high and middlebrow white culture—European art music [and] contemporary American poetry” to create the popular music of the day. Gershwin would find his first compositional success from the Alley with the song “Swanee” in 1919. The hit, popularized by noted minstrel performer and Broadway star Al Jolson, is emblematic of a relationship to Black music and stories that characterizes Gershwin’s output, encompassing both genuine, deep admiration and a more appropriative or extractive tendency.

On the one hand, Gershwin espoused, “Jazz I regard as an American folk music; not the only one, but a very powerful one which is probably in the blood and feeling of the American people more than any other style of music.” But, as Robby Greenberg has pointed out in BBC Music Magazine, “Gershwin [was not] close to the black folk roots of jazz”—in fact, his iconic Rhapsody in Blue premiered with an all-white band.

Gershwin’s success on the Alley soon translated into a growing Broadway career. He created a number of musicals in the early 1920s, works in which he developed a close collaboration with his brother, Ira Gershwin. But perhaps the defining event of his career would take place in 1924 with his participation in bandleader Paul Whiteman’s concert “An Experiment in Modern Music” at New York’s Aeolian Hall, where he premiered Rhapsody in Blue at the piano.

Met with rave reviews, the premiere would mark the beginning of a creative period in which Gershwin would produce most of his classical works—the Piano Concerto in F was completed the following year and An American in Paris shortly after the second of two trips to Paris (in 1926 and 1928). This output did not slow his work as a Broadway songwriter, as he penned some of his best-known tunes (“Embraceable You,” “I Got Rhythm”) during this decade.

The grand unification of these two sides of Gershwin came with the 1935 premiere of Porgy and Bess. Though now considered amongst his seminal works, it did poorly at the box office—in its aftermath, Gershwin decamped to Hollywood where he would spend the final two years before his untimely death at 38.

The Music

Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony (before its 1928 merger with the Philharmonic), was at the Rhapsody premiere and asked Gershwin to compose the Concerto in F shortly thereafter. (On the transformative power of Gershwin’s piano playing, the conductor Serge Koussevitzky remarked, “As I watched him, I caught myself thinking, in a dream state, that this was a delusion; the enchantment of this extraordinary being was too great to be real.”)

While completed and premiered before his pilgrimages to Paris (which brought him into contact Nadia Boulanger, Alban Berg, and other classical luminaries of the day), the concerto, as its name might indicate, hewed closer to classical conventions (and was, according to musicologist Wayne D. Shirley, the first large-ensemble work Gershwin orchestrated himself). A lifelong pianist, Gershwin performed it at the premiere (and with the San Francisco Symphony in 1937, shortly before his passing the same year).

The titanic first movement is defined by a “Charleston groove”—a syncopated rhythmic motive which Gershwin develops around the orchestra with heightening chromatic intensity before the roll of a snare drum announces the piano’s first, rhapsodic entrance. Gershwin proves the short motive to be endlessly mutable, coaxing lush, pianistic melody and double-timed energy from the same figure. Just as it seems lyricism might win the day in a rapturous Technicolor E-major melody shared by piano and ensemble, Gershwin shifts us—first into a driven groove punctuated by arpeggiated flashes. The piano then pulls back into a slower, unaccompanied scherzando which slowly builds again to the movement’s pyrotechnic conclusion.

The slow movement opens with an unhurried, sentimental blues first expressed in the trumpets and clarinets and supported by gentle, walking strings. The piano defines the movement’s middle section, leading a playful interlude which repeatedly gallops, halts, and picks up again. A concertmaster solo leads back into the movement’s opening material, which is dramatized at greater scale. Just as in the first movement, a heroic swell cedes unexpectedly—this time to a tender interlude in D-flat major, which closes the movement.

Gershwin himself said of the third movement: “The final movement reverts to the style of the first. It is an orgy of rhythms, starting violently and keeping to the same pace throughout.” The opening figure, a flurry of repeatedly struck notes, finds the solo piano at its most percussive. But a delicate synthesis of materials from the previous movements is at work underneath the finale’s bounding energy. We hear echoes of the blues and Charleston figures, and yes—one more false climax—en route to an energetic grand finale.

An American in Paris

George Gershwin

Work Composed: 1928

SF Symphony Performances: First—July 1931. Artur Rodzinski conducted. Most recent—July 2022. Ludovic Morlot conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbal, bells, snare drum, small tom-tom, large tom-tom, bass drum, wood block, xylophone, and taxi horns), celesta, and strings

Duration: About 17 minutes

Gershwin’s first trip to Paris in 1926 was an attempt to ground himself more firmly in classical conventions. Seeking the tutelage of the pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, he was rejected, just as Maurice Ravel had rejected him as a student during a visit to New York (more out of admiration than any deficiency—the French composer is said to have remarked, “Why become a second-rate Ravel when you’re already a first-rate Gershwin?”). Gershwin returned from his trip with orchestral sketches, which, after a second visit to the city in 1928, would become An American in Paris.

The symphonic poem, written for a sizeable orchestra with an especially healthy corps of percussion instruments (including four car horns and a celesta), is full of the influence of Tin Pan Alley and the facility with American vernaculars that Ravel prized, as well as the chromaticism, dissonance, and complex development of thematic materials found in the music of Gershwin’s classical icons.

The Music

The jaunty first melody (sometimes known as the “walking theme”), taken up by the violins, vividly evokes the early 20th-century city. The opening minutes, contrapuntal and excitable, develop this melody, alongside several secondary themes, across the sections of the orchestra (notable contrasting elements include a scampering xylophone and brass interjections mimicking car horns). The energy begins to dwindle until a singing, impressionistic exploration of the same theme led by the English horn and oboes emerges. The more leisurely paced interlude is marked by solo playing from many of the orchestra’s principal players, highlighting the wide range of timbral potential at the disposal of the large ensemble.

Other themes then assert themselves—most notably, a yawning “blues theme” carried by the trumpet and supported by brushed snare, wood block, saxophone, and flute. The trombone emerges, then hands the melody to the strings who plumb its lyrical depts. It recedes gently before a final main theme—a syncopated, strutting melody—is introduced in the brass. The materials mingle begin to mix and overlap in ever-quicker intervals, but it is the blues that wins the day and ends the piece triumphantly.

Harlem

Duke Ellington

(orch. Luther Henderson)

Born: April 19, 1899, in Washington, DC

Died: May 24, 1974, in New York

Work Composed: 1950

SF Symphony Performances: First—July 1999. Keith Lockhart conducted. Most recent—May 2023. Thomas Wilkins conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 alto saxophones, 2 tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, suspended cymbal, bell, cowbell, tam-tam, shakers, gourd, drum set, tom-toms, and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 18 minutes

The prominent jazz trumpeter and academic Gunther Schuller once proclaimed Duke Ellington’s output as a composer—“thousands of works [with] many hundreds that are true masterpieces”—to be “a record matched only by Johann Sebastian Bach.” Ellington was as prolific a pianist and bandleader as he was a composer, and his legacy is central to the history of jazz and American music writ large.

His 50 years of relentless activity resulted in the composition of jazz works from standards to album-length suites, musical short films and full film scores, and symphonic and choral pieces. One of the towering figures of jazz’s prewar big-band era, Ellington’s music remained influential and distinctive despite seismic shifts in the form’s sensibilities and sound, integrating elements of swing, bebop, and modal jazz into his mid- and late-career oeuvre.

Born in Washington, DC, to two pianists, a young Edward Kennedy Ellington’s zeal for the instrument soon eclipsed his passion for baseball and his studies in commercial art, leading him into a burgeoning career as a performer and bandleader in the city. By the turn of the 1920s, he had begun to establish himself in Harlem, assembling his band of longtime collaborators en route to a 1926 residency at the famous Cotton Club.

The next decade would see Ellington and his orchestra feature in film and issue recordings of important tunes like “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing).” But the dual specter of segregation and the Great Depression limited performance and recording revenues stateside—Ellington took to touring with his group throughout Europe while experimenting with arrangements for smaller ensembles in the United States.

But despite growing critical and popular attention shifting towards small-ensemble swing before and during the war, Ellington ran largely against the grain. His emergent working relationship with composer, pianist, arranger, and longtime collaborator Billy Strayhorn (whom Ellington met in 1939) pushed him towards the creation of longer compositions like the musical Jump for Joy (1941) alongside the orchestral Black, Brown and Beige (1943) and Harlem (1950).

Now considered one of Ellington’s most important works, Black, Brown and Beige was received poorly, a critical response which musicologist Scott DeVeaux suggests wounded Ellington deeply. It would take a 1956 appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival to return Ellington to the critical and commercial spotlight. He took full advantage of the resurgence that followed, which prompted a flurry of recordings and compositions.

These included several album-length jazz suites for his orchestra inspired by his touring travels, collaborations with the next generation of luminaries (among them Ella Fitzgerald, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and John Coltrane), and large-scale vocal works—the three “Sacred Concerts,” concert-length pieces which fused jazz and Christian liturgical traditions, and an opera, Queenie Pie, unfinished at the time of his death in 1974.

The Music

Paying homage to the sounds of the New York neighborhood where Ellington cut his teeth at the Cotton Club, Harlem was written as Ellington’s orchestra toured Scandinavia, Germany, and Switzerland. It was commissioned by Arturo Toscanini for the NBC Symphony, but was instead premiered by Ellington’s band at an NAACP benefit held at New York’s old 39th Street Metropolitan Opera House. Ellington describes it as “a concerto grosso for jazz band and symphony orchestra,” meant to document various scenes of the neighborhood. Ellington’s original liner notes describe the elements documented as follows:

1. Pronouncing the word “Harlem,” itemizing its many facets—from downtown to uptown, true and false;

2. 110th Street, heading north through the Spanish neighbor-hood; 3. Intersection further uptown–cats shucking and stiffing; 4. Upbeat parade; 5. Jazz spoken in a thousand languages; 6. Floor show; 7. Girls out of step, but kicking like crazy; 8. Fanfare for Sunday; 9. On the way to church; 10. Church—we’re even represented in Congress by our man of the church; 11. The sermon; 12. Funeral; 13. Counterpoint of tears; 14. Chic chick; 15. Stopping traffic; 16. After church promendade; 17. Agreement a cappella; 18. Civil Rights demandments; 19. March onward and upward; 20. Summary–contributions coda.

The piece opens with a sultry pair of thirds in a solo “growl trumpet” (intended to mirror the syllables of “Har-lem” according to orchestrator Maurice Peress). The figure widens and fluctuates with modal and dissonant colors before launching into a comfortable swing which slows periodically to meditate in freer time. A saxophone solo over pizzicato strings brims with quiet charm.

Just as the swing pauses once more, Ellington launches into a fast-paced rhumba clearly evocative of Spanish Harlem. An angular piano begins to poke out of the texture and emerges as a primary voice during the first interpolation of a faster swing music that begins to alternate with the rhumba rhythm. The rotation intensifies into a bebop fervor that demands virtuosity from nearly every section of the orchestra, building continually before collapsing under its own weight.

A coolheaded, extended ad lib is dominated by wandering solos in the clarinet, bass clarinet, and trombones, sometimes interacting in sinuous polyphony. As if from nowhere, a surging snare leads into a menacingly slow, staggering swing—the “Big Back Beat.” Trumpets wail in close four-part harmony, reminiscent of Ellington’s 1930s arrangements as a bandleader. The bass clarinet soothes the squealing horns, which cede to more temperate saxophones and trombones.

The trumpets return at the virtuosic height of their range in the piece’s final stretches. Interrupted momentarily by a racing, highly percussive interlude, their sonority takes the lead again in the staggering wall of sound at the piece’s conclusion.

—Lev Mamuya

About the Artists

James Gaffigan

James Gaffigan serves as music director of Komische Oper Berlin, where he begins his third season in 2025–26. Guest engagements this season include returns to the Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Music Academy, and Houston Grand Opera. In Europe, he makes return engagements with the NDR Elbphilharmonie, Les Arts Valencia Opera, and the Verbier Festival.

Gaffigan regularly works with the New York Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, and Metropolitan Opera, among many others. In Europe, he has appeared with the London Symphony, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, Munich Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Norwegian Opera and Ballet, Deutsches Symphonie Orchester Berlin, Staatskapelle Berlin, and Czech Philharmonic.

Gaffigan’s previous titles include music director of the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía in Valencia, Spain; principal guest conductor of both the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and the Trondheim Symphony Orchestra and Opera; chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony; and assistant conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in December 2006 and served as Associate Conductor from 2006 to 2009. He returns to the SF Symphony later this season for a special concert with Yo-Yo Ma (June 1) and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (June 18, 20, 21).

“Growing up in New York City, I got to meet all sorts of people from all types of backgrounds. My high school was a microcosm for our country, and it was beautiful. I wish everyone had the opportunity to experience that. Tonight’s program is extraordinary music, all rooted in our country and its diverse people and communities.”

—James Gaffigan

Hélène Grimaud

Hélène Grimaud is not just a deeply passionate and committed musical artist, but also a wildlife conservationist, a human rights activist, and a writer. She has been an exclusive Deutsche Grammophon artist since 2002. Her recordings have been awarded numerous accolades, including the Cannes Classical Recording of the Year, Choc du Monde de la musique, Diapason d’or, Grand Prix du disque, Record Academy Prize (Tokyo), Midem Classic Award, and Echo Klassik Award. Her contributions have been recognized by the French government, which admitted her to the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur at the rank of Chevalier.

Recent projects include For Clara, focused on the ties that bound both Robert Schumann and his protégé Brahms to the pianist-composer Clara Schumann. Concert highlights include appearances with the London Philharmonic, Luxembourg Philharmonic as part of a residency at the Luxembourg Philhar-monie, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Camerata Salzburg.

Grimaud was born in Aix-en-Provence, was accepted into the Paris Conservatory at 13, and won first prize in piano performance three years later. She continued to study with György Sándor and Leon Fleisher until she gave her debut recital in Tokyo in 1987. That same year, Daniel Barenboim invited her to perform with the Orchestre de Paris. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist in February 1993.

David H. Miller is an assistant professor of practice in music and American studies at UC Berkeley. His research focuses on modernist music, particularly that of Anton Webern, and its performance and reception in the United States. At Cal, he has taught courses on J.S. Bach, interwar American music, and postwar American experimentalism. As a performer, he focuses on Baroque double bass and viola da gamba, and directs the University Baroque Ensemble. He holds a BA in music from Harvard University and a PhD in musicology from Cornell University.