In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, January 29, 2026, at 7:30pm

Friday, January 30, 2026, at 7:30pm

Saturday, January 31, 2026, at 7:30pm

Inside Music Talk with Scott Foglesong, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

On stage at 6:30pm before each performance

Jaap van Zweden conducting

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K.503 (1786)

Allegro maestoso

Andante

Allegretto

Emanuel Ax

Intermission

Anton Bruckner

Symphony No. 7 in E major (1883)

Allegro moderato

Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam (Very solemn and slow)

Scherzo: Allegro–Trio: Etwas langsamer (Somewhat slower)

Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht schnell (With movement but not fast)

Inside Music Talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Nearly a century after Mozart, Anton Bruckner composed his Symphony No. 7, in part as a tribute and memorial for Richard Wagner. This sprawling symphony became Bruckner’s first success and the most popular during his life.

Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K.503

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1786

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1957. Enrique Jordá conducted with Leon Fleisher as soloist. Most recent—November 2013. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Jeremy Denk as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

Before the 19th century, most composers wrote in a wide spectrum of genres, whether operatic or choral, orchestral or instrumental. That said, most displayed clear penchants for certain genres over others. In Mozart’s case we find a strong attraction not only to opera but also to the piano concerto, a preference dictated as much by practicality as by personality. Mozart was a pianist, indeed the first of the great composer-pianists, and he wrote his piano concertos for himself, typically performed during his lengthy subscription concerts during the 1780s.

Just how long those concerts were is witnessed by a letter from Mozart to his father Leopold listing the program for his March 26, 1783 concert at the Burgtheater. The amount of music presented is downright daunting by modern standards: the Haffner Symphony No. 35 (with its finale repeated for a closer), two piano concertos, three arias, one concert rondo for voice and orchestra, and a movement from a serenade. Mozart was even happy to take requests from the audience.

Mozart may have reached his highest compositional peak in 1786–87, the time of The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni; of the E-flat–major Piano Quartet; of the Kegelstatt Trio for piano, clarinet, and viola; of Symphony No. 38, Prague; of the beloved Eine kleine Nachtmusik; of the C-major and C-minor string quintets; of canons and rondos and sonatas and quartets and dances and variations and lieder.

And three piano concertos that stand at the apex of the art. No. 23 in A major is beguiling, winsome, light-footed and nimble; No. 24 in C minor is appropriately dark and brooding. But the standout is No. 25 in C major, surely among Mozart’s noblest and most imposing conceptions, on par with the Jupiter Symphony. It doesn’t seem to have been recognized as such at first, and in fact its full acceptance had to wait until well into the 20th century. But it is in many ways Mozart’s own Emperor concerto, in particular in regards to its first movement, the longest among his concertos and a tour de force of structure and dramatic pacing.

The Music

A word is in order regarding the form of a concerto’s first movement as developed by Mozart in the 1780s. Traditional teaching typically dictates a “double exposition” layout in which the orchestra first states the movement’s materials—primary theme, secondary theme, closing theme—alone and without any key change. That’s followed by the soloist’s entrance, after which those materials are repeated but with the secondary and closing themes stated in a contrasting key.

That sounds fine until we examine Mozart’s later piano concertos and discover that they don’t really work like that. Not only does Mozart employ more themes than just the standard three, but he uses them in bracingly original and unpredictable ways. His concerto themes tend to behave like actors in a play; they enter, exit, collude, separate, jockey for position, and sometimes hog more than their fair share of the limelight. Some themes are assigned to the orchestra only; others might be the piano’s sole provenance. Mozart’s first movements still retain the basic trappings of classical sonata form, in that they carve out a rhetorical arc powered by largescale contrasts between keys, but one gets the distinct impression that they’re doing that mostly to keep up appearances. Considerable dialog takes place, not only between solo and orchestra, but between the very thematic materials themselves as they arise, persist, then subside within the complex sonic tapestry of a solo instrument interwoven with orchestra. There’s just something irresistibly chatty about it all, like a busy stage scene in which everybody has news to share and everybody has comments to make.

The opening manifests such broad-shouldered grandiloquence that the musicologist Donald Francis Tovey imagined it as kicking off a largescale choral work on the order of a Gloria or Dixit Dominus, rather than a piano concerto. Mozart spices the mix with darting allusions to the minor mode, a harbinger of the major-minor duality that is to prevail through the entire movement, such as the jaunty “Marseillaise” secondary theme that is stated first in minor, then repeated in major. Following the orchestra-only exposition, the soloist enters through a side door, as it were, via brief snippets that evolve into a modestly virtuoso display before the majestic primary theme kicks off the second exposition. With that, a gallimaufry of themes ensues, sometimes led by the soloist, other times the orchestra, separated by passages of dazzling keyboard embroidery. Mozart didn’t write out a cadenza for the movement, leaving it up to the soloist to decide what’s going to happen—an on-the-spot improvisation or something planned out in advance, or even a cadenza written by another composer. (We may assume that Mozart, a spectacular improviser, came up with his cadenza on the spot.)

First-time listeners might find the second-place Andante a bit puzzling. This isn’t the usual Mozartian opera aria with the singer morphed into a keyboard. There’s something downright discursive about it, its themes made up of short statements rather than the customary liquid vocal lines. (Michael Steinberg, the SF Symphony’s late program annotator, has likened it to a knot garden in the moonlight.) Unlike most slow movements, it’s structured in classic sonata form, albeit without the midway development section. Mozart does not linger unduly over his materials; the movement runs its course with remarkable economy and ends in a delicate upwards spray of octaves in the piano solo.

With the concluding Allegretto we’re on more familiar Mozartean turf with what comes across as the first-act finale in a comic opera—all a-twitter with constant comings and goings, interjections and interruptions and arguments, the whole bound together by a bouncy, strutting reprise theme. An intervening episode creates a wistful mood by way of a softly-contoured melody that provides Mozart with no end of developmental potential. Frequent exuberant passages in triplet rhythms eventually bring the concerto to a jolly close, an optimistic ending for this imposing landmark of a concerto.

Symphony No. 7 in E major

Anton Bruckner

(ed. Leopold Nowak)

Born: September 4, 1824, in Ansfelden, Upper Austria

Died: October 11, 1896, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1881–83

SF Symphony Performances: First—May 1947. Pierre Monteux conducted. Most recent—November 2016. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 4 Wagner tubas, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle and cymbals), and strings

Duration: About 60 minutes

Ansfelden, Austria is a delightful little town. It’s got green spaces, fresh air, senior centers, golf courses, decent if limited shopping, and Chinese takeout. For anything fancier, Linz is one freeway exit away, and if that’s not enough, Vienna is about three hours east on the A1.

Anton Bruckner was born in an Ansfelden that was a world removed from today’s pretty suburb. In the early 19th century it was an impoverished rural hamlet with more cows than people and shortages both of food and decent jobs. It must have seemed like the end of nowhere to a talented young chap like Anton, son of a village schoolmaster. His father got him started in music, then in his early teens he was sent off to the nearby Augustinian monastery of Sankt Florian, which was to play a critical role throughout his life. (And posthumously as well; he’s buried in the monastery’s crypt.) The sound of the mighty Sankt Florian organ runs throughout Bruckner’s works, as does the monastery’s reverent, timeless atmosphere.

Organist at Sankt Florian, ditto in nearby Linz. It was a quiet, unassuming life. He studied mostly via correspondence with the renowned music theorist Simon Sechter, and when Sechter died in 1868, Bruckner took over his beloved teacher’s theory classes at the Vienna Conservatory. The shy and unsophisticated Bruckner, a village and monastery man down to his toes, was a poor fit for Vienna’s toxic musical politics. He had a rough time of it with both the Viennese intelligentsia and the critics; Brahms referred to him as “that bumpkin” and arch critic Eduard Hanslick skewered one of his works as a “symphonic anaconda.” But he persisted amid a steady shower of brickbats, continued to produce luxuriantly epic symphonies, and eventually found a measure of success with Viennese musicians and their notoriously fickle public. He stayed unmarried—not for lack of trying—and died in his humble but comfortable Vienna apartment at the age of 72. It took a while for posterity to catch on, but catch on it did. Nowadays Bruckner ranks among the supreme masters of the late Romantic symphony. His music even survived appropriation by the Nazis, a use contradictory to its fundamental nobility and goodness.

The Seventh Symphony stands apart from its predecessors as having been accepted as a repertory item almost from the get-go. Bruckner finished it in September 1883, and two now-legendary conductors—Arthur Nikisch and Hermann Levi—set it on its way in 1884 and 1885, respectively. Amazingly enough, it had made its way to Chicago by 1886 thanks to that enterprising American conductor Theodore Thomas. Its immediate and lasting popularity isn’t at all difficult to understand. It’s not quite as lengthy as most of its brethren, but most importantly, it has a special sweep and a compelling inner urgency. Even if it might seem silly to describe an hour-plus symphony as economical, the word is actually quite apt. Impressively grand, majestic, and passionate, the Bruckner Seventh propels itself firmly along its destined journey. It isn’t just that it comes off as good. It comes off as right.

The Music

Time is the essential element in a Bruckner symphony. It is not our time; it is Bruckner’s time; it is the time of the unruffled pastures of Sankt Florian; it is the time of nature and the gradual unfolding of the seasons. To expect otherwise from a Bruckner symphony is to wind up with the white knuckles and cracked tooth enamel of a seething driver stuck in rush-hour traffic. Far better to forget about the freeway and think instead of carriages on sun-dappled country roads, where other travelers are rarely encountered and our arrival time is mostly up to the horse.

The symphony opens in rapt luminosity. The initial two paragraphs of the first movement are relaxed, unhurried, even limpid. It’s only in the third paragraph that there’s a clear contrast as the music acquires an unmistakable spring in its step. That duality between patient expansiveness and brisk alertness continues through the movement, which is structured in an expanded sonata form in which the divisions between exposition, development, and recapitulation are blurred. It culminates in an incandescent blaze of radiant E-major chords.

The minor-mode second movement, in rondo form and marked to be played solemnly and slowly, can be described as peak Bruckner. It is here that Bruckner’s use of low brass—including Wagner tubas—provides a sonic chiaroscuro that perfectly complements the measured tread of the main reprise. But it isn’t all seriousness and gloom, as the contrasting episodes range from sweetly lyrical to nobly dignified. The movement ends in major mode, offering reassuring balm after its prevailing mournfulness.

Ever since Beethoven, it had become the norm for symphonies to replace the ubiquitous minuet with a scherzo, which retains the minuet’s triple meter as well as its overall three-part layout. But that’s where the resemblances end. Classical minuets are either courtly or rustic, but scherzos are fast and furious, sometimes edging on frenzy. Here Bruckner whips up an absolute corker of a scherzo, almost minimalist in its hypnotic repetition of a martial tocsin in the brass underpinned by nonstop pulsations in the bass. The central trio, a lovely thing that positively hums with Viennese gemütlichkeit, provides welcome relief.

The finale starts out like a happy-go-lucky variant of the first movement, but before long it begins to demonstrate considerable fortitude. At climatic moments Bruckner throws the orchestration textbooks out the window by requiring every single instrument in the orchestra to play in unison and at maximum volume. Disconcerting, to say the least. But it’s vintage Bruckner, absolutely and manifestly Bruckner. “They want me to write differently,” he once remarked. “Certainly I could, but I must not.”

—Scott Foglesong

Scott Foglesong is a Contributing Writer and Inside Music Speaker for the San Francisco Symphony and chair of music theory and musicianship at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. He also writes program notes for the California Symphony, Oregon Symphony, and Grand Teton Music Festival, among other organizations. As a pianist, he studied at the Peabody Conservatory and SFCM.

About the Artists

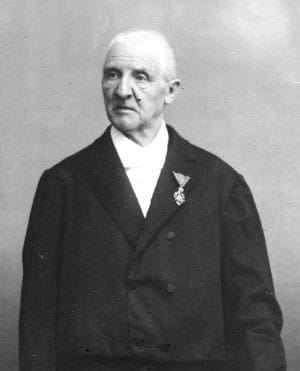

Jaap van Zweden

Jaap van Zweden is music director of the Seoul Philharmonic and music director designate of Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. Among his past music directorships are the New York Philharmonic, where his tenure included 31 premieres and the reopening of David Geffen Hall, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which was named Gramophone’s Orchestra of the Year under his leadership. He has conducted the Vienna Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Berlin Staatskapelle, London Symphony, Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among many others. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in October 2012, led this season’s Opening Gala with Yuja Wang in September, and will lead the Orchestra in a three-season cycle of Beethoven’s nine symphonies beginning with Nos. 2 and 7 this February.

This season, van Zweden undertakes European and Asian tours with Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and rejoins the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, and Antwerp Symphony, where he is conductor emeritus. In the United States, he returns to the Chicago Symphony and leads his first US tour with the Seoul Philharmonic. In Asia, he returns to the NHK Symphony Orchestra and the Hong Kong Philharmonic.

Van Zweden’s discography includes acclaimed releases on Decca Gold and Naxos. With the New York Philharmonic, he recorded David Lang’s prisoner of the state and Julia Wolfe’s Grammy-nominated Fire in my mouth. With the Hong Kong Philharmonic, he conducted the first full Ring cycle ever staged in Hong Kong, and his performance of Parsifal received the 2012 Edison Award for Best Opera Recording.

Born in Amsterdam, van Zweden was appointed the youngest-ever concertmaster of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at age 19, and began his conducting career in 1996. A winner of the Concertgebouw Prize and Musical America’s 2012 Conductor of the Year, he founded the Papageno Foundation with his wife, supporting young people with autism through music, housing, research, and innovation.

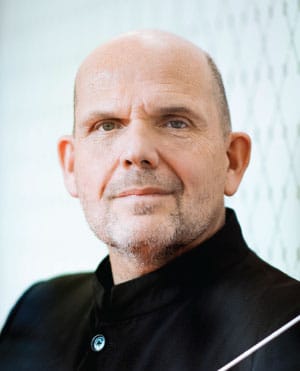

Emanuel Ax

Born to Polish parents in what is today Lviv, Ukraine, Emanuel Ax moved to Winnipeg, Canada, with his family when he was a young boy. He made his New York debut in the Young Concert Artists Series, and in 1974 won the first Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Tel Aviv. In 1975 he won the Michaels Award of Young Concert Artists, followed by the Avery Fisher Prize. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 1979.

This season, Ax performs with the Philadelphia Orchestra at Carnegie Hall and on tour to Tokyo, Seoul, and Hong Kong. This month he performs John Williams’s Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony, following his premiere of it at Tanglewood last summer. Ax also returns to the Dallas Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, Los Angeles Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, Charleston Symphony, Madison Symphony, Naples (Florida) Philharmonic, and New Jersey Symphony.

Ax has been a Sony Classical exclusive recording artist since 1987. He launched a multi-year project with violinist Leonidas Kavakos and cellist Yo-Yo Ma to record all the Beethoven trios and symphonies (arranged for trio), of which the first four discs have been released. He has received Grammy Awards for the second and third volumes of his cycle of Haydn’s piano sonatas. He also made a series of Grammy-winning recordings with Ma of the Beethoven and Brahms cello sonatas. In 2005, Ax contributed to an International Emmy Award–winning BBC documentary commemorating the Holocaust that aired on the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. In 2013, Ax’s recording Variations received an Echo Klassik Award for Solo Recording of the Year.

Ax is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary doctorates of music from Skidmore College, New England Conservatory of Music, Yale University, and Columbia University.