In This Program

- Welcome

- In Celebration: Chris Gilbert

- In Good Time With Esa-Pekka Salonen

- SF Symphony Musicians Celebrate Salonen

- Salonen Year By Year

- The Annotator Looks Back

- Community Connections

- Meet the Musicians

- Print Edition

Welcome

Over the past five years, Esa-Pekka Salonen has led the San Francisco Symphony through a transformative era, defined by exceptional creativity and artistic exploration. It is only fitting that Esa-Pekka has chosen Mahler’s Second Symphony—a work of profound significance to the San Francisco Symphony—to conclude both the 2024–25 season and his tenure as Music Director.

Collaboration has been at the heart of Esa-Pekka’s leadership. His work with the Symphony’s eight Collaborative Partners, along with signature projects with artists like Peter Sellars and Alonzo King, has pushed the boundaries of what an orchestra can be. The richly multisensory production of Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire, created with pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet and Cartier, brought audiences an experience unlike anything seen before.

Championing new music has also been a hallmark of his tenure. Through key commissions and premieres, Esa-Pekka has amplified the voices of composers including Gabriella Smith, Samuel Adams, Fang Man, Anders Hillborg, Jesper Nordin, Magnus Lindberg, and Emerging Black Composers Project winners Trevor Weston, Jens Ibsen, and Xavier Muzik. Deeply inspired by the creative energy of California, Esa-Pekka also helped launch the California Festival: A Celebration of New Music, reflecting the Golden State’s innovative spirit.

Under his leadership, the Symphony has expanded its reach through groundbreaking media projects. From early digital productions such as Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale and LIGETI: PARADIGMS to a Grammy-winning recording of Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater and a new partnership with Apple Music Classical, Esa-Pekka has ushered the Symphony into a new era, bringing its artistry to audiences around the world.

Perhaps his most lasting legacy is the extraordinary group of musicians he has welcomed into the orchestra. With the appointment of 20 new musicians—including several principals—he has laid the foundation for the Symphony’s bright future.

We are deeply grateful for all that Esa-Pekka has brought to the San Francisco Symphony. His impact will resonate for years to come, and as we step into a new chapter, we look ahead with excitement to what the future holds.

Priscilla B. Geeslin

Chair, San Francisco Symphony

In Celebration

With the close of the 2024–25 season, we bid farewell to bassist Chris Gilbert, who is retiring from the San Francisco Symphony in August.

A native of St. Louis, Gilbert studied with Henry Loew at the University of Southern Illinois for two years and at the St. Louis Conservatory for a year. He was a substitute musician in the 1978–79 season before joining the San Francisco Symphony as a permanent member in December 1979, under Edo de Waart.

We thank him for his many years of service to the San Francisco Symphony and we wish him well.

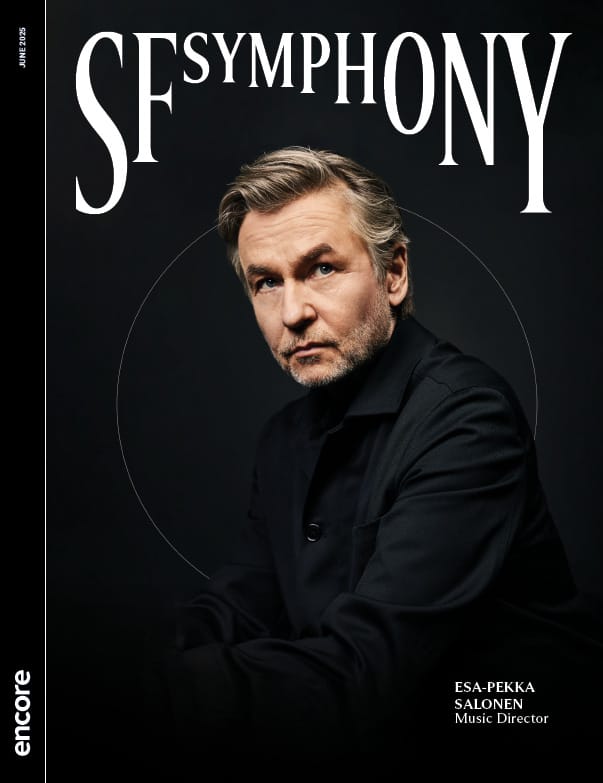

In Good Time

Esa-Pekka Salonen looks back on his time as SF Symphony Music Director • Tim Grieving

THE PANDEMIC SHUTDOWN OF 2020 arrived at a moment of major transition for the San Francisco Symphony, silencing the stage as Michael Tilson Thomas prepared to take his final bows as music director and Esa-Pekka Salonen was about to assume the mantle. What was meant to be a celebratory handoff became a season of cancellations—no farewell concerts for Tilson Thomas, and no official debut for Salonen.

The past few years have brought their share of challenges, but as Salonen embarks on his final concerts in his final season as San Francisco’s music director, he is in a thoughtful, grateful mood—quick to praise this orchestra and to think fondly on his time here.

“I inherited a very good orchestra,” he says, via Zoom from Salzburg, where he is rehearsing Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra for the Salzburg Easter Festival.

The Finnish double threat, 66, began his composing career in the early 1980s with a concerto for saxophone and orchestra. He made his conducting debut in 1979, with his hometown Finnish Radio Symphony, and was appointed music director of the Swedish Radio Symphony in 1985. A last-minute substitution for Tilson Thomas in London in 1983 attracted the attention of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, who lured him to America in 1992—and for the next 17 years he significantly reshaped the Los Angeles orchestra. It was in the midst of his tenure in LA when he was invited to conduct the San Francisco Symphony for the first time.

He still vividly remembers that debut, on Thursday, April 1, 2004—a program that included the West Coast premiere of his piece Insomnia (composed in the wake of 9/11) and Prokofiev’s First Piano Concerto. The audience that week met the visiting conductor with ecstatic standing ovations, and Salonen has “a very nice memory of the concert, and the way it went, and the way the orchestra played,” he says. “And of course it was very different, temperamentally, from the Los Angeles Philharmonic—which is not a surprise, obviously. So it took me a little bit of adjusting to get used to their way of reacting to things and so on. But this is normal. This happens always when a conductor goes to a new orchestra; it’s a mutual adjustment process, basically—reaction, impulse, reaction, feedback.”

When asked what exactly that unique temperament is, he muses: “It’s interesting how some of the DNA of an orchestra doesn’t change. The San Francisco Symphony then, already, I thought had this very pronounced lyrical quality to their playing, and a sort of natural, expressive, beautiful phrasing that they were intuitively producing, without any particular guidance from me on the box. This was like their default position. I thought: that’s interesting, because it’s still there, the expressive turn of the phrase. I think it’s been there for a long time, since the days of, I don’t know, Pierre Monteux maybe…”

“Sometimes,” he adds, “certain traditions are passed on from generation to generation, and we don’t quite know how it works. I’ve seen this so many times but I’m not sure what exactly the mechanism is, whether it’s some kind of osmosis, or whether it’s verbal—or whether it’s just like when fish swim in a perfect formation, so they synchronize their movements perfectly and we don’t quite know what the mechanism is, because we don’t know who the lead fish is. But it’s just like, one fish reads the three closest ones, and so on. It’s a slightly mysterious thing, but it’s there.”

Salonen spent much of his post-LA Phil years concentrating on writing his own music. But when, in 2018, this lyrical school of fish invited him to be their next music director, he called it a “no-brainer.”

Despite navigating the learning curve that faced this new maestro-orchestra relationship—an aborted inaugural season, tentative first concerts back with distanced audiences and smaller ensembles—he fell into an easy rhythm with the players. “That happened surprisingly and impressively quickly,” he says. He specifically thinks back on their performances of Mahler’s Second Symphony in October 2022, his first time conducting Mahler with his new orchestra. “MTT/SFS has been the official Mahler combo for decades, and before the first rehearsal I was imagining trying to kind of steer a train or something like that. But it wasn’t a train; it was totally open. ‘Okay, we know this piece very well, but what do you want to do with it?’ And I thought: all right—I have arrived. That was a significant moment.”

Salonen also inherited a diverse, omnivorous programming tradition from Tilson Thomas. “It felt very easy for me to take over from MTT in this way,” he says, “because his programming has been like a model for us younger conductors. But what he did, what he has always been doing, has been very open, very curious, very provocative at times, and sometimes the juxtapositions he has come up with have been absolutely brilliant. He did that a lot in San Francisco, so they were not particularly surprised by what I was doing, because it wasn’t that far off from their bread-and-butter.”

20

New musicians hired by Esa-Pekka Salonen, including four principal players and Chorus Director Jenny Wong

16

New audio recordings, including releases on SFS Media via Apple Music Classical and a Grammy-winning Deutsche Grammophon recording of Saariaho’s Adriana Mater

15

World and US premieres conducted by Salonen

5

Digital video productions featuring Salonen

3

Staged productions in collaboration with director Peter Sellars

Salonen looks back at many highlights and cherished moments in these past five years. There were a number of premieres—piano concertos by both Nico Muhly and Magnus Lindberg, Strange Beasts by Emerging Black Composers Project winner Xavier Muzik, No Such Spring by Samuel Adams, and more. And while he doesn’t want to name any favorites, Salonen is happy to say “there have been a few premieres where we all felt that, okay, we have been the midwife to something that will have a long life. That’s the most satisfying thing. And obviously we cannot predict that, but when you collectively sense that, okay, this is important—that’s a really good feeling.”

New recordings during his time in San Francisco have included warhorses by Stravinsky, Berlioz, and Prokofiev, as well as spatial audio recordings of the music of Ligeti. The most poignant and personal for Salonen was the premiere recording of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater. “Peter Sellars and I premiered the opera in Paris in 2006, and worked closely with Kaija,” he says. “It was just a coincidence that Kaija passed away during the week of rehearsals for the concert performance of her opera, and her daughter was my assistant conductor. Here we were, having another crack on it—without her. And then to have a document made of that, I think that’s very important, personally.” The recording won a Grammy earlier this year for Best Opera Recording.

Salonen acknowledges the challenges facing the organization while emphasizing the special relationship he has cultivated with the musicians of the Orchestra during his time here. “I’ve been so impressed and touched by the quality and commitment on stage every night,” he says, “We cannot control what happens outside. But somehow, every concert has been highly enjoyable, and very intense in my experience.”

He already knows what he’ll be doing on the first morning after his final concert—which is Mahler’s Second Symphony, appropriately, on June 14. He’s in the midst of composing a concerto for Stefan Dohr, principal horn of the Berlin Philharmonic, and the premiere is in August. “Most likely,” he says, “I will get up early and go back to writing.”

John Williams: A Composer’s Life (Oxford University Press, September 2025). Find him at timgreiving.com.

SF Symphony Musicians Celebrate Salonen

I’m so grateful for the time we’ve had together with you as our Music Director. Your ability to inspire, communicate, and shape the music for our common purpose—to help our audiences to feel, be moved, and even to transform their inner life in a crazy and overstimulated world. Thank you for the gift you’ve given all of us.

—Cathy Down, Violin

Thank you, Esa-Pekka, for hiring me and welcoming me into this amazing orchestra. You and the musicians have given me the musical life I’ve always dreamed of. I’ve been moved, inspired, and charmed countless times in rehearsals and concerts with you, and will cherish those memories.

—Anonymous

Thank you for bringing your inspiring vision to the SF Symphony. It has been an exhilarating musical journey with you.

—In Sun Jang, Violin

It has been such a joy collaborating with you. I will cherish memories of our European tour, your fantastic compositions, and your musical integrity and artistry holding the music above all else. With many thanks and best wishes for the future.

—Suzanne Leon, Violin

A memory: It was in a week of performances of the Brahms Violin Concerto directed by Esa-Pekka with Augustin Hadelich as soloist. The two of them had an extraordinary sense of connection. Hadelich’s playing was inspired and flawless while Salonen displayed his ability to sensitively follow the soloist and seamlessly lead the orchestra at the same time, moving and shaping the music as the orchestra responded with aplomb. It resulted in a consummate performance of profound music making.

—Stephen Tramontozzi,

Assistant Principal Bass

I’ll forever be grateful to Esa-Pekka for introducing the Orchestra to the creative genius of director Peter Sellars! The innovative projects they brought to our stages, Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater, Stravinsky’s Oedipus rex, Schoenberg’s Erwartung—difficult, thorny, complex works that were given vivid life with deep understanding and emotional punch. It was enlightening and so inspiring to witness their musical collaborations.

—Barbara Bogatin, Cello

The final step of my audition was an interview with the Music Director, and I was more nervous than ever. But Esa-Pekka was kind and congratulatory in our conversation, and I’m honored to have been hired by someone whose leadership and captivating vision always bring out the best in us. We will miss you, EPS!

—Anonymous

I have appreciated working together with EP very much during what seems like too short of a time. Not only is he amazing to work with on the podium, but I have especially appreciated playing his works. From the virtuosic vibraphone writing in Nyx, the metal drum-set writing in the Violin Concerto, or the very cool tabla-esque hand drumming in the Cello Concerto, his music has always been the most fun to put together as a percussionist.

—Jacob Nissly, Principal Percussion

During one of EPS’s first rehearsals we were playing Beethoven’s 6th and in the third movement there is a section played by the celli of rustic repeated notes. When we got there, EPS stopped and said, “no, play it like you’re that drunk guy in the pub who keeps repeating the same annoying story over and over, very loudly, until everybody leaves.” Then, as he gave the upbeat to start us back up, he said, under his breath, “that will be me in a few years!” That perfectly set the tone for his sense of humor!

—Jeremy Constant,

Assistant Concertmaster

Thank you for your artistic vision and enthusiasm for innovation over these past five seasons with the SFS. You are a consummate professional under whose direction the orchestra has grown into a powerful and nimble ensemble. Your unwavering support of the musicians has been heartwarming and we are sorry to see you go!

—Melissa Kleinbart, Violin

I am so grateful for being able to work with Esa-Pekka for my first professional orchestra experience! It has been a steep learning curve, but his calm and clear leadership quickly made me feel right at home. I will always remember the humorous stories he told in rehearsal.

—Davis You, Cello

I will always be grateful to Maestro Salonen for trusting me with a job at the SF Symphony. I will look back at our time spent working together as very meaningful, a profound artistic vision executed with efficiency, respect, and an incisive yet warm sense of humor. I also share a love and fascination for a lot of the music we played together, especially the 20th-century masterpieces by composers such as Bartók and Stravinsky, and of course, HK Gruber’s Frankenstein!! Thank you so much for everything, Maestro.

—Leonid Plashinov-Johnson, Viola

It is with great foresight and generosity that EPS gives so freely to his young and talented conducting students. It has been a pleasure to work with the Salonen Fellows, who have so benefited from the guidance and career focus that has been instilled in them by such an incredible role model.

—Anonymous

Earnest consistency is EPS’s trademark. Each night he consistently demands from all of us nothing less than highest level of performance. His unique DNA will leave a great footprint and legacy in the fabric of this orchestra.

—Raushan Akhmedyarova, Violin

Not everyone knows this, but EPS is renowned for his excellent taste in beer. When he told me and my brewing partner, Mark Wright, that he loved the Kölsch we brewed, it was a pretty great day. We make sure he has a couple cold ones in his fridge backstage whenever he is in town. Kippis!

—Paul Welcomer, Trombone

Esa-Pekka once told me that there are no saints in Finland. I would say there is at

least one.

—Anonymous

Salonen Year By Year

Esa-Pekka Salonen’s five-year tenure as Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony embraced a rapidly shifting world—from the global pandemic to the rise of AI and immersive technologies—championing expansive collaborations and new ways of connecting through music. Take a tour through his visionary leadership.

2020–21

In an inaugural season shaped by pandemic restrictions, Salonen and the Symphony discovered inventive ways to create and connect. The 2020–21 season opened with Throughline, a digital program featuring Salonen, Symphony musicians, and all eight Collaborative Partners. Spring brought an array of digital projects, including two SoundBox programs curated by Salonen. After 14 months, live concerts returned with a special program performed for frontline workers who supported the people of San Francisco in critical ways throughout the pandemic.

2021–22

In a powerful return to the stage, the 2021–22 season celebrated renewed collaboration and innovative storytelling. Re-Opening Night set the tone with a dynamic showcase of music and movement featuring Alonzo King LINES Ballet and Collaborative Partner esperanza spalding. Director Peter Sellars unveiled the first of several striking staged productions to come: Stravinsky’s Oedipus rex and Symphony of Psalms. Stravinsky was also the focus of a compact black-box–style digital production of The Soldier’s Tale, directed by Netia Jones, while the digital release LIGETI: PARADIGMS unveiled an AI-driven collaboration with pioneering media artist Refik Anadol.

2022–23

The 2022–23 season expanded Salonen and the Symphony’s artistic reach, from major international stages to exciting new collaborations at home. Joined by Collaborative Partners Nico Muhly and Claire Chase, Salonen led the Orchestra on an international tour with residencies in Paris and Hamburg. Back in San Francisco, he and Peter Sellars paid tribute to the late Kaija Saariaho with a stunning staged production of Adriana Mater. A new partnership with Apple Music Classical signaled the next chapter in the Symphony’s rich recording legacy. The season came to a rousing close with electrifying performances of Busoni’s towering Piano Concerto by artist-in-residence Igor Levit.

2023–24

Salonen’s 2023–24 season was marked by bold new partnerships that spanned states—both literal and metaphysical. The California Festival: A Celebration of New Music spotlighted contemporary composers in a groundbreaking statewide initiative. A collaboration with Cartier brought an unprecedented fusion of music, light, and scent to Scriabin’s Prometheus, The Poem of Fire. Meanwhile, Peter Sellars and choreographer Alonzo King returned to the Symphony for a striking double bill of dance and theater—Ravel’s Mother Goose and Arnold Schoenberg’s haunting monodrama Erwartung.

2024–25

The 2024–25 season has brought both artistic milestones and celebration. Salonen and the Symphony marked a historic first together—winning a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording for Saariaho’s Adriana Mater. Salonen the composer took center stage as Principal Cello Rainer Eudeikis performed his Cello Concerto under the composer’s own baton. Salonen’s deep exploration of Stravinsky’s music continued with performances of The Firebird and The Rite of Spring. The season now culminates in a powerful finale as Salonen closes his tenure with Mahler’s Symphony No. 2.

The Annotator Looks Back

By James M. Keller

After 25 years as the San Francisco Symphony’s Program Annotator, James M. Keller is retiring at the end of the season. Over the course of his tenure, he has written the majority of the Symphony’s program notes and SFS Media liner notes, covering nearly 2,000 orchestral, chamber, and solo works. Our concerts and recordings have been enriched by his knowledge and insight, and he will remain a contributor to the program book.

One of the great boons for a music lover coming of age in the 1960s was that classical recordings took the form of LP records packaged in cardboard sleeves, the ample backsides of which were mostly filled with program notes. The sleeve was sealed by some sort of transparent plastic, but—and this is important—you could nonetheless read the program note in the store without buying the record. The hands-down coolest label was budget-priced Nonesuch Records, which disseminated a vast variety of music, from the middle ages to the latest piece by George Crumb. More often than not, their program notes were by Edward Tatnall Canby. I practically memorized some of his sleeve notes, including for pieces I would not actually hear until years afterward. Many eminent professors would enlighten or confuse me later on, but they were all building on a foundation laid in the ’60s by Edward Tatnall Canby’s writings. As a teenager, I viewed them as an exalted literary genre of their own: novels, plays, poems, program notes.

I did most of my growing up on the outskirts of Reading, Pennsylvania, a city of diminishing population that was past its glory days as an industrial powerhouse but nonetheless boasted a respectable symphony orchestra. I convinced my parents that I needed to avail myself of this resource, so my father, who had shown no previous interest in classical music but ended up falling head over heels for it, shepherded me on five Sunday afternoons each year to the balcony of the theater downtown. The orchestra was supported in no small part by the city’s cultural doyenne, heiress to one of Reading’s manufacturing fortunes, and her largesse extended to writing not only checks but also program notes. The second half of one program included The Unanswered Question by Charles Ives (1874–1954)—a milestone work by America’s modernist pioneer. I read her program note during intermission:

Charles Ives, born at Ware in 1600 (baptized July 20), was a vicar choral of St. Paul’s Cathedral. In 1633 he was engaged, together with Henry and William Lawes, to compose the music for Shirley’s masque, “The Triumph of Peace,” performed at Court by the gentlemen of the Four Inns of Court on Candlemas Day, 1633–34, for his share in which he received £100.

It continued through to his death in 1662 and a striking conclusion: “The Unanswered Question is Ives’ most famous composition.”

Then they played the piece. Something smelled off, even to a ninth-grader (though one schooled in the essays of Edward Tatnall Canby). Later that week I headed to the Reading Public Library and made a beeline to Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians—the third edition (1927), which was the most recent they owned. I found no entry for Charles Ives, but there was one for Simon Ives, who was “born at Ware in 1600 (baptized July 20), was a vicar choral of St. Paul’s Cathedral” . . . and so on, word for word, except for the conclusion about The Unanswered Question being his most famous composition—the only original prose in the whole program note. From this I learned important lessons: (a) writers should make an effort to get facts right, and (b) plagiarism is not a good look. In my 14-year-old perfection, I thought I could do better than that.

The opportunity arrived the following year, when my high school chorus and orchestra optimistically performed Part One of Handel’s Messiah. I pressed the director to let me contribute a program note. I enjoyed writing it, and I think it wasn’t awful. I had started down a primrose path that led me through college, conservatory, and graduate school, writing all the way. One opportunity led to another, and eventually I began working my way up as the annotator for orchestras in New York, where I was living: first the Brooklyn Philharmonic for a few years (directed by Lukas Foss, followed by Dennis Russell Davies), then the Orchestra of St. Luke’s (Roger Norrington, Charles Mackerras), finally the New York Philharmonic (Kurt Masur). In fact, I began at the New York Philharmonic as half of a team hired in 1995—Michael Steinberg as Program Annotator and me as Program Editor plus Annotator for all their chamber concerts. That meant I was learning at the knee of the profession’s master. Michael was already well loved for his work with the San Francisco Symphony, where he served as Program Annotator from 1979 to 2000.

We worked as hand to glove for five years, and by the end of that time he was running out of steam, which afforded me more opportunities to serve as the de facto annotator. By 2000, he felt ready to relinquish his daily duties at both orchestras. Writing this, I realize that he was then the age that I am now—and I really do understand!

I was invited to succeed him as Program Annotator of the New York Philharmonic, and days later the San Francisco Symphony asked me to assume the same position here. The SF Symphony and I were already acquainted. I had been lightly involved with the American Festival, which, in 1996, capped off Michael Tilson Thomas’s first year as Music Director, and then in ensuing seasons I had provided occasional program essays and had given preconcert lectures, of which I would deliver some 350 until things shut down during COVID times.

It was, for me, a dream job. My work days unrolled with predictable sameness, but they were never really the same. I would spend them hobnobbing with cherished friends like Mozart, Mendelssohn, or Ives (Charles, not Simon), researching whatever piece was on the docket, reading the score, listening‚ and then distilling everything into an essay of predetermined word-count to inform and entertain concertgoers, and, in the best of cases, inspire them to explore further on their own. I hope my program notes will continue to do that even as I withdraw from active duty after 25 years, perhaps even spurring the interest of some musically inclined Bay Area teenager who is just embarking on the exploration of a lifetime.

Community Connections

Yerba Buena Gardens Festival

Yerba Buena Gardens Festival enhances the vitality and quality of life in the parks and open spaces of Yerba Buena Gardens in downtown San Francisco through the curated presentation of admission-free music, dance, circus, poetry, theater, children’s programs, and cultural celebrations reflecting the rich cultures and creativity of the region. Artistic excellence, inclusion, diversity, and innovation are at the heart of YBGF’s mission. Its programs strive to provide audiences with a greater understanding of diverse art forms and cultural heritages. Everyone—regardless of circumstance or ability to pay—needs and deserves the joy, inspiration, and communal experience that only live performance offers. Presenting over 100+ programs each summer, Yerba Buena Gardens Festival is always free, outdoors, and fresh! For more information on its landmark 25th Anniversary Season, visit ybgfestival.org.

Meet the Musicians

Matthew Griffith • Associate Principal and E-flat Clarinet

Matthew Griffith joined the San Francisco Symphony as Associate Principal and E-flat Clarinet in 2022. He previously served as acting assistant principal clarinet with the North Carolina Symphony and the Nashville Symphony, and was a member of TŌN (The Orchestra Now), a graduate-level training orchestra based at Bard College. A native of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, he holds degrees from Yale University and New England Conservatory, and was a Tanglewood Music Center Fellow.

Do you remember the first concert you played with the San Francisco Symphony?

The first full concert I played was Star Wars: Episode IV, which was also the first time I’d done a movie with a big screen in a professional orchestra. There’s a lot of pressure playing in a new hall, so it was nice that it was a little bit more of an informal setting, as well as such an exciting feature in the first week of the season.

How did you begin playing clarinet?

I started with a plastic toy recorder. My parents bought me one when I was really young, and after school I would try to play my favorite melodies from video games and TV shows. I think that naturally led to clarinet in fifth grade.

Did you have some especially influential teachers?

My first teacher was Dr. Jill Hanes in the Sheboygan area. She got me going and was part of the reason I stuck to it through middle and high school. To this day she is very supportive. Later I also studied with Todd Levy, who is the principal clarinet of the Milwaukee Symphony, and he transformed my sound to the next level and introduced me to this whole world of professional orchestras and auditions. My most recent teacher was Michael Wayne. He was wonderful about bringing me back to the basics and guiding me all the way into the most advanced stages of my career. I am incredibly grateful that I was able to have such amazing mentorship.

You play E-flat clarinet, which is the small, soprano member of the family. Did you intend to specialize in it?

I’ve had to play a lot of bass clarinet and E-flat over the years in school and beyond, but when it comes to auxiliary instruments, I think I always had a little more of an affinity for E-flat—I enjoy playing it, and over time that has made me a specialist.

Which pieces use E-flat clarinet?

The E-flat and D clarinets gained traction in the 19th century, starting with Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, and ever since they have been used in many of the major works that everyone recognizes. One of the first pieces I played in San Francisco that showcased this type of clarinet was Stravinsky’s The Firebird. The instrument’s also commonly found in Mahler, Shostakovich, Richard Strauss, Bartók, Ravel. . . a lot of pieces we did in my first season here.

I understand you’re also a computer programmer.

That’s right! I started getting into computers growing up, because my brother would find cool software to install, like RPG Maker for making role-playing games. I didn’t quite realize I was falling into computer programming from these applications, but eventually I was learning C++ and winning national competitions. I did a double major in college with music and computer science.

Was there a moment when you had to decide on clarinet over programming?

I’ve always wanted to do both to the fullest extent that I can. The window of opportunity for a career in classical music is generally much smaller, so I’ve had to put more time and focus on that to find the right balance. But I still keep going with programming—I make video games with a team of people online, and my daily routine and practicing methods are largely run by computer programs I’ve made.

Photo: Kristen Loken

Print Edition