In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, October 19, 2025, at 7:30pm

Marc-André Hamelin piano

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, Opus 106, Hammerklavier (1817)

Allegro

Scherzo: Assai vivace

Adagio sostenuto: Appassionato e con molto sentimento

Largo–Allegro risoluto (Fuga a tre voci)

Intermission

Robert Schumann

Waldszenen (Forest Scenes), Opus 82 (1849)

Eintritt (Entry)

Jäger auf der Lauer (Hunters Lying in Wait)

Einsame Blumen (Lonely Flowers)

Verrufene Stelle (Haunted Place)

Freundliche Landschaft (Friendly Landscape)

Herberge (Wayside Inn)

Vogel als Prophet (Bird as Prophet)

Jagdlied (Hunting Song)

Abschied (Farewell)

Maurice Ravel

Gaspard de la nuit (1908)

Ondine

Le Gibet

Scarbo

The Music for Families Series is supported by

Program Notes

Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, Opus 106, Hammerklavier

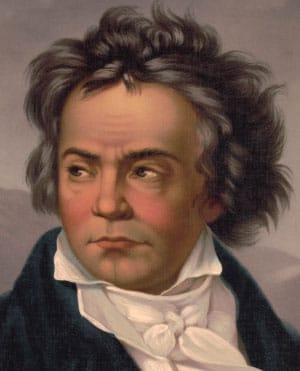

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1817

“Now there you have a sonata that will keep the pianists busy when it is played 50 years hence,” Ludwig van Beethoven reportedly told publisher Domenico Artaria in 1819 in reference to his just-finished Opus 106. For once Beethoven actually underestimated one of his creations. At the cusp of its third century, the Hammerklavier still keeps pianists busy as they embark on an arduous journey marked by inspiration, invigoration, intimidation, frustration, headache, heartbreak, and repetitive strain injury.

Even that nickname Hammerklavier breathes of challenge, of confrontation—despite being merely the German word for pianoforte and indicative of Beethoven’s determination to promote German nomenclature over Italian. It could just as easily apply to the preceding sonata Opus 101, also indicated as being written für das Hammerklavier on its title page. But the name is a particularly apt description of Opus 106, described by biographer Jan Swafford as “Beethoven’s ultimate hammer thrown at the pleasing, popular, amateur tradition of the piano sonata.”

This massive and herculean sonata required a two-year gestation. It dates from a relatively fallow period during Beethoven’s career, between the miraculous middle period of 1803–13 and the 1820s of the Ninth Symphony, Missa solemnis, and the final string quartets. As of January 1816 Beethoven had emerged victorious—at least in his opinion—after a tension-wracked year-long battle with his widowed sister-in-law Johanna for the custody of her son Karl. Even if the grinding rounds of legal briefs and court appearances were over for the time being, Beethoven’s productivity had dwindled precipitously. He was not malingering by any means; he kept up a busy schedule supervising performances of his works and still managed to play the (very) occasional piano recital, despite his hearing being almost gone. But he wasn’t writing very much.

Beethoven completed his Opus 101 in late 1816. He produced nothing substantial for almost an entire year, but towards the end of 1817 his creative force asserted itself anew. By April 1818 he had not only completed the first two movements of the Hammerklavier but had also begun preliminary sketches on what would become the Ninth Symphony. By the autumn of 1818 the Hammerklavier was complete—all four movements of it, all nearly 1,200 measures of it, all 45 some-odd minutes of it.

That abundance establishes itself from the get-go; whereas most sonata-form movements make do with a single primary theme, or perhaps two under special circumstances as established by the arbiters of formal structure, the Hammerklavier gives us at least three. The first theme doesn’t consist of much, just a rising third followed by an upper neighbor tone and completed by a descending third. Counting the vaulting left-hand leap that sets things going, it consists of eight notes that outline three discrete pitches: B-flat–D–E-flat, punching out a tocsin to Beethoven’s patron the Archduke Rudolph: Vivat, vivat Rudolph! That tocsin is repeated a third higher, on D–F–G.

And in that repetition we find a compelling clue to Beethoven’s ultimate strategy: the interval of a third. The very opening of the sonata outlines a third (albeit stretched over more than two octaves); the theme falls by a third at the end; the repetition of the theme is by thirds; some of the critical key changes move by thirds. All in all, thirds will prove to be the germinating force not only in this movement but throughout the sonata in general; the themes of both Scherzo and Adagio, and even the subject of the massive concluding fugue, all deal in leaps of a third. This is not to say, however, that the listener will hear a progression of similar-sounding, thirds-outlining themes throughout the sonata; to the contrary, each theme is strongly individualized and there is no sense of an idée fixe running through the work like a trail of breadcrumbs. All those thirds do their stuff behind the scenes, as it were. As ace commentator Donald Francis Tovey quips so amusingly and perceptively, “the separate movements of a sonata lose their own momentum and achieve but a flaccid and precarious unity if they try to live by taking in each other’s thematic washing.”

The remaining primary themes traffic in that underlying interval of a third, each in its own way, after which multiple secondary themes and a pair of closing themes round out the exposition. An extensive development even includes a fugal passage; the recapitulation proceeds more or less according to established principles but gives way to a marvelous coda during which the Vivat drumbeat dies away gradually.

The second-place Scherzo, that minuet-on-steroids that Beethoven had made so uniquely his own since his early days, contrasts a jittery, nervous reprise with a galumphing Trio that gives way to an unexpected cadenza-like transition before resuming its initial high-strung skittishness. The following Adagio sostenuto–Appassionato e con molto sentimento, in the wholly unexpected key of F-sharp minor (it sounds a third down from the home key of B-flat major), unfolds as an extended lament, the longest slow movement in all Beethoven, once described as “a mausoleum of collective suffering of the world.”

Such a majestic sonata requires an appropriately imposing ending, and after an extended introductory Largo we enter the realm of fugue—and what a fugue it is! Propulsive, complex, and rhythmic, it employs the full gamut of learned contrapuntal devices and techniques to create an affirmation of the sheer power of music in a thrilling dramatic debate that seems to take for its topic nothing less than a full-scale confrontation with the cosmos itself.

Waldszenen, Opus 82

Robert Schumann

Born: June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony

Died: July 29, 1856, Endenich, near Bonn

Work Composed: 1848–49

Into the woods: since antiquity European culture has maintained a strong connection to the forest as an idealized realm and a primal source of spiritual essence. Consider Shakespeare’s forest of Arden in As You Like It or its cousins in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Two Gentlemen of Verona. The Germans, ever partial to forest idylls, refer to Waldeinsamkeit, alone-time in the woods. It’s not a coincidence that the first German Romantic opera, Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz, takes place in a forest with all its allure, magic, and dark mystery.

Robert Schumann was at his best when channeling his surging emotional currents through his compositions, and nowhere does he do that more than in his works for solo piano. Personal, intimate, and confessional, they can seem well-nigh autobiographical or even psychotherapeutic. In the Waldszenen of 1849, Schumann allowed his imagination free rein in a series of contemplations about the woods as metaphor for our internal selves and our relationship with the larger world. The individual pieces may be short and made up of thematic fragments, but they pack a bevy of associations and resonances. This is no humdrum foray into the woods, in other words: it is a journey into the psyche, comforting and beautiful on the one hand, unknowable and mysterious on the other.

The nine Waldszenen, written over a mere three days, explore Romantic forest symbolism at its most evocative while often edging into chaotic disruptions, formal ambiguities, and seeming non-sequiturs. At first, all is peaceful with Eintritt (Entry), our first steps into the wood characterized by soothing harmonies and engaging melodies. But we’re not alone: Jäger auf der Lauer (Hunters Lying in Wait) pursue their prey with noisy enthusiasm. After all that excitement, a pair of flower pieces: Einsame Blumen (Lonely Flowers), disarmingly simple and yet occasionally jarred by fleeting wrong-note dissonances, followed by Verrufene Stelle (Haunted Place), in which we enter the realm of the Gothic via a poem by Friedrich Hebbel describing a dark red flower that takes its color not from the sun, but from the earth “which drank human blood.” Nota bene: Clara Schumann refused to play Verrufene Stelle in public, finding it just too grim.

The darkness is dispelled soon in Freundliche Landschaft (Friendly Landscape), chummy and roly-poly, its aura of well-being only intensified by the well-cushioned coziness of Herberge (Wayside Inn).

Vogel als Prophet (Bird as Prophet) encapsulates the essence of Schumann’s thoughts. To describe it as a mere imitation of birdsong (although Schumann does a pretty good job with that) is to ignore the apparent incongruity of the middle section, a gravely lovely chorale-like affair reminiscent of the lyric musings of the song-cycle Dichterliebe. Thus human consciousness is juxtaposed with a flittering aural fantasy, shunning both explanation and justification.

Apparently those hunters from the second piece had a good day, given their hunting song Jagdlied, all hail-fellow-well-met jollity and ruddy good cheer. Then it’s time to say Abschied (Farewell) to the woods, hopefully renewed and reinvigorated by the experience, but perhaps a bit reluctant to return to the real world after the woodland realm’s enchantment.

Gaspard de la nuit

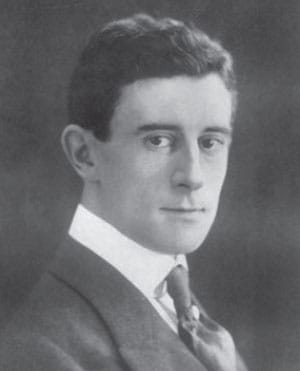

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1908

It is a general rule of thumb that the great piano composers were themselves great pianists. Consider Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, Debussy, and Rachmaninoff, all of them superlative performers whose piano writing reflects their acute awareness of the interaction between body and keyboard. Maurice Ravel stands apart as an undisputed master piano composer who was himself only a middling pianist. But one needn’t look very far to understand why that would be so. Ravel was not only the son of an inventor and clockmaker, but he was himself fascinated by the logistics of moving objects, as witnessed by his collection of whirring mechanical toys. Thus it makes sense that he would write intricate piano music that is built around the capabilities and limitations of two hands and ten fingers as they move around both the keyboard and each other, joined by the two feet on the pedals.

With Gaspard de la nuit, Ravel aimed to extend his pianistic ingenuity to the breaking point. That makes for a supreme test of a pianist’s technique, and it is not for nothing that French pianist Alfred Cortot described it as “one of the most astonishing examples of instrumental ingenuity ever contrived.” Ravel himself couldn’t play Gaspard, and for some time it was restricted to a tiny circle of pianists, particularly super-virtuoso Ricardo Viñes, who played the premiere in 1909. That didn’t last, and nowadays Gaspard is universally embraced by virtuosos as pianistic catnip.

If the three pieces making up Gaspard de la nuit were only fancy finger-benders, they probably wouldn’t justify the trouble. But there’s far more to them than that. Consummate realizations of poetic vision in sound, they’re worth it and then some. Ravel based the suite on an eponymous 1830 set of fantastical prose poems by a sickly and bohemian young writer named Aloysius Bertrand, born in 1807 and dead in 1841 at age 34. The sketches cover a wide range of topics and characters, echoing writers as diverse as Rabelais, Byron, Hugo, and Chaucer.

Ravel chose three of Bertrand’s pieces for his piano suite, starting with the mythological water nymph Ondine, seductress who seeks a human male. “Listen! Listen! It is I, it is Ondine who grazes with these drops of water the sonorous diamond-shaped panes of your window made resplendent by the mournful rays of the moon,” she cries. Ravel’s setting is appropriately aqueous, conjuring up dazzling sprays of pianistic figurations around an elusive, languid melody.

Ondine is followed by the stark horror of Le gibet, which the theorist Charles Rosen has described as “a creation of tension through insistence, like … water torture.” A single repeated note resounds throughout the movement, representing the “bell that sounds at the walls of some town, beyond the horizon, and it is the carcass of a hanged man that reddens the setting sun.”

To conclude, the dazzling Scarbo, portraying the sinister dwarf who haunts us in the night: “How many times have I heard his laugh humming in the shadows of my bedroom alcove, and his nail grinding along the silk of the curtains around my bed!” Ravel’s hallucinogenic and quicksilver setting ends precisely as Bertrand’s sketch does: “his countenance turned pale, like the wax at the candle’s end, and all at once he vanished away.”

—Scott Foglesong

About the Artist

Marc-André Hamelin

Marc-André Hamelin’s 2025–26 season began with a tour of Australia and Asia, featuring concerto and recital appearances with the Sydney Symphony, concerto engagements with the Wuxi, Ningbo, and Shenzhen symphonies, and solo recitals in Adelaide, Xiamen, and Shenzhen. In North America, he appears this season with the Philadelphia Orchestra, San Diego Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and on tour with Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. European appearances include the Bavarian State Orchestra, Tonkünstler Orchestra, Bremen Philharmonic, Wigmore Hall, Schubertiade, MDR Wartburg, and Chipping Campden Festival. Further recitals take place in Italy, the Netherlands, and Berlin, along with an extensive duo tour with pianist Maria João Pires.

An exclusive recording artist for Hyperion Records, Hamelin has released 92 recordings including a broad range of solo, orchestral, and chamber repertoire. This month, Hyperion releases Found Objects / Sound Objects, a recording of contemporary works. Recent recordings include Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata as well as Dvořák and Price quintets with the Takács Quartet. Also a noted composer, Hamelin has written more than 30 works, many of which are published by Edition Peters.

Hamelin is the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the German Record Critics’ Association, as well as more than 20 of its quarterly awards. Other honors include eight Juno Awards, 11 Grammy nominations, the 2018 Jean Gimbel Lane Prize from Northwestern University, and the Paul de Hueck and Norman Walford Career Achievement Award from the Ontario Arts Foundation. Hamelin is an Officer of the Order of Canada, a Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Québec, and a member of the Royal Society of Canada. Born in Montreal, Hamelin lives in the Boston area with his wife, Cathy Fuller, a producer and host at Classical WCRB. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in November 2006.