In This Program

The Concert

Friday, September 12, 2025, at 7:00pm

Jaap van Zweden conducting

John Adams

Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986)

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 23 (1875)

Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso–Allegro con spirito

Andantino semplice–Prestissimo

Allegro con fuoco

Yuja Wang

Ottorino Respighi

Pines of Rome (1924)

The Pines of the Villa Borghese

Pines Near a Catacomb

The Pines of the Janiculum

The Pines of the Appian Way

This program is presented without intermission.

The Opening Gala concert is generously sponsored by the William and Gretchen Kimball Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 has Yuja Wang enter with a series of now-iconic chords, but the piece was initially rejected by Tchaikovsky’s intended soloist, who advised him to throw it all out. Instead, the composer stuck with it. The ensuing music interweaves Slavic folk songs and orchestral splendor.

Ottorino Respighi’s Pines of Rome is a vivid postcard from the Eternal City. Look out for its innovative use of a recording to portray a real nightingale.

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

John Adams

Born: February 15, 1947, in Worcester, Massachusetts

Work Composed: 1986

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1986. Edo de Waart conducted. Most recent—January 2025. Mark Elder conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 piccolos, 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 4 clarinets, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion (woodblocks, pedal bass drum, snare drum, large bass drum, suspended cymbal, sizzle cymbal, large tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, glockenspiel, xylophone, and crotales), 2 synthesizers, and strings

Duration: About 4 minutes

The relationship between the San Francisco Symphony and John Adams spans nearly half a century, beginning in 1979 with his appointment as an adviser on contemporary music. It was in the early years of this collaboration—especially during his tenure as the Symphony’s first composer in residence from 1982 to 1985—that Adams was launched on the path to becoming one of the most influential and widely performed living composers. The residency championed his orchestral voice just as he was beginning to shape it, and also helped pioneer a new model for composer residencies at American orchestras.

Short Ride in a Fast Machine is a compact, adrenaline- charged concert opener, composed the year after Adams’s residency had culminated in the epic Harmonielehre, whose resoundingly successful premiere in 1985—performed in this very hall—marked a decisive breakthrough. Commissioned for the 1986 opening of the Great Woods Center for the Performing Arts—a new outdoor amphitheater in Mansfield, Massachusetts, now known as the Xfinity Center—Short Ride was taken on its inaugural spin by the Pittsburgh Symphony under the baton of none other than Michael Tilson Thomas. Decades later, MTT paired Short Ride with Harmonielehre on a San Francisco Symphony recording (on SFS Media) that won the 2013 Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance.

The Music

Short Ride in a Fast Machine should be enjoyed as a boisterously in-your-face, virtuoso roller coaster ride of orchestral sonorities. Adams offered a wry comment on the title when first introducing the piece: “You know how it is when someone asks you to ride in a terrific sports car, and then you wish you hadn’t?”

The immediacy of this music’s impact belies the ingenious craft behind its construction. Short Ride offers a high-voltage snapshot of how Adams minted a powerfully original musical language drawing from the building blocks of minimalism as well as other American styles he had internalized from his early years—all transmogrified by an irrepressibly exuberant imagination.

Like a metronome gone rogue, the woodblock’s steady, insistent pulse collides with overlapping patterns—first in the trumpets—that create thrilling tension and rhythmic dissonance through their simultaneity. The swirling patterns of repeated, tight motifs gain added energy from hints of big-band brass and swing, channeling the presence of Duke Ellington. In the final section, the woodblock suddenly drops out, as if the motor driving the music has finally broken loose—leaving momentum to carry the piece, unhinged, to its breathless conclusion.

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Opus 23

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1874–75

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1912. Henry Hadley conducted with Tina Lerner as soloist. Most recent—November 2024. Nicholas Collon conducted with Conrad Tao as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

In a deliciously ironic twist of music history, one of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s best-loved works received its world premiere not in his Russian homeland, but in Boston—introducing the then-35-year-old composer’s music to the United States for the first time. Even more astonishing is that the now-iconic First Piano Concerto was, at first, flatly rejected by the very virtuoso Tchaikovsky had hoped would bring it to life.

That pianist was Nicolai Rubinstein, one of the most influential musical figures in 19th-century Russia and the cofounding director of the Moscow Conservatory, who had invited the promising young composer to join the faculty at the institution’s inception. Acclaimed as a dazzling virtuoso and piano lion of the era, Rubinstein was an obvious authority to consult, and Tchaikovsky hoped his feedback would lend practical insights and pave the way to a premiere. Instead, he was met with a tirade.

According to Tchaikovsky’s own account, shared a few years later with his patron, Nadezhda von Meck, he visited Rubinstein on Christmas Eve in 1874 to play through the score in an empty classroom at the Conservatory. Tchaikovsky had drafted the concerto in a mere six weeks and had only the orchestration left to complete, which he did by early February 1875. “Worthless, utterly unplayable,” thundered Rubinstein in response to the play-through. At best, he conceded, “two or three pages were worth preserving”; otherwise, the rest “must be thrown away or completely rewritten.”

Tchaikovsky proudly recalled his reply: “I shall not alter a single note; I shall publish the work exactly as it stands!” In reality, he did make some alterations before the premiere and still more for the edition published in 1879. An even later edition, prepared in 1889 but not printed until after the composer’s death, introduced further changes, the authenticity of which remains the subject of spirited debate. Still, it is this final edition that became the standard version of the concerto performed by generations of pianists.

Following Rubinstein’s rejection, Tchaikovsky found a willing advocate in Hans von Bülow, the eminent German pianist and conductor, who embraced the new concerto with enthusiasm. Thus it was that Bülow introduced Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto to the world in the fall of 1875 at the Boston Music Hall, accompanied by a pickup orchestra comprising music students mostly from Harvard (the Boston Symphony would not be founded for another six years). Tchaikovsky himself could not attend the premiere, which proved much more successful than the concerto’s first Russian performance the following month, in Saint Petersburg. Meanwhile, Rubinstein had a change of heart and not only agreed to conduct the Moscow premiere in December but also went on to become one of the work’s early champions in Russia as a soloist.

The Music

A four-note motif, proclaimed with theatrical flair by the horns, sets the stage for the piano’s early, grand entrance. Just how grand that entrance should be is a key point in the debate over authenticity. Tchaikovsky’s original version called for sweeping rolled chords, but the now-standard “hammered” approach of percussive block chords was codified in the posthumous edition. These emphatic chords accompany a passionately soaring melody first presented by the orchestra, which unfolds in a lengthy introduction but is then abandoned, never to be repeated—though aspects of the material return in subtler ways later in the work.

The “real” first theme of the opening movement slips in furtively, like a change of scene, and was adapted from a Ukrainian tune Tchaikovsky reportedly heard whistled by a beggar in the marketplace. This is the first of several folk elements Tchaikovsky weaves into the concerto—a strategy that has a parallel in the way composers like John Adams recast vernacular references within classical contexts. A poetic, delicately lyrical second theme initially resembles a dreamy reverie but is transformed in the course of the movement. The long solo cadenza toward the end emerges as a play within a play—a microcosm of the piano’s far-ranging personality in the concerto.

The ensuing Andantino semplice fuses the calming lyricism of a traditional slow movement with a playful, scherzo-like interlude—

a whirring detour that bursts in at the center. Ignited by a catchy, folk-tinged theme of fiery spirit, the finale once again taps into Ukrainian song, this time one associated with spring. A lyrical second theme enters modestly, but at the culmination of the movement it is magnified into a moment of neon-bright splendor—a transformation that recalls the grandeur of the lush, soaring melody heard at the very start of the concerto.

Pines of Rome

Ottorino Respighi

Born: July 9, 1879, in Bologna, Italy

Died: April 18, 1936, in Rome

Work Composed: 1923–24

SF Symphony Performances: First—October 1926. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—May 2025. Giancarlo Guerrero conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 6 offstage Roman buccine (2 trumpets and 4 trombones), timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, bells, tambourine, ratchet, and bass drum), harp, celesta, piano, organ, recorded birdsong (nightingale), and strings

Duration: About 23 minutes

Although he came of age in Bologna, Ottorino Respighi spent his formative years abroad. He arrived in Russia in 1900, seven years after Tchaikovsky’s untimely death, to take up a post as violist with the orchestra of the Russian Imperial Theatres in Saint Petersburg. It was during this impressionable period that he came under the influence of Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov. A brief period of study in Berlin followed, deepening the itinerant Italian’s understanding of structure and symphonic form.

Respighi studied with Rimsky-Korsakov privately, later recalling “a few, but for me very important, lessons in orchestration.” The influence was profound. The Russian’s principles of vivid instrumental color, the bold use of contrasts, and the establishment of fantastical atmospheres found a lasting home in Respighi’s imagination. Nowhere is this legacy more amply on display than in his brilliant Roman soundscapes.

Resettling in Rome in 1913, Respighi accepted a position as professor of composition at the storied Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. Its resident orchestra had been founded just five years earlier, becoming the first Italian ensemble to focus exclusively on symphonic repertoire, and it was the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia that gave the world premiere of Pines of Rome (Pini di Roma). Though opera had become the traditional domain for Italian composers, Respighi’s enduring reputation rests on his symphonic works—above all Pines of Rome, which remains the best-known work from his prolific output.

Composed between 1923 and 1924, Pines of Rome stands at the center of a triptych of symphonic poems inspired by various facets of the Eternal City, from its natural beauty and ancient grandeur to its vibrant popular traditions—with a particular focus on its classical past and mythic lore. Its composition followed that of Fountains of Rome (Fontane di Roma), the work that first brought Respighi international acclaim, which was completed in 1916. Later, in 1928, came Roman Festivals (Feste Romane).

The Music

For Pines of Rome, Respighi turned to the unifying image of Rome’s signature umbrella pine trees. Like its companion works, it unfolds in four sections, evoking the shape of a symphony, but the effect is closer to a series of cinematic tableaux than to traditional symphonic architecture.

The first movement depicts the innocent play of children in the pine grove of the lavish Villa Borghese gardens, which Cardinal Scipione Borghese had laid out on the grounds of former vineyards. The children, as Respighi wrote in his commentary on the work, dance “the Italian version of ‘Ring around-a-rosy,’ mimic marching soldiers and battles, and twitter and shriek like swallows at evening, coming and going in swarms.”

A scene change whisks the listener to a dark, shadowy soundscape, where pines stand sentinel over the entrance of a catacomb. “From the depths rises a chant that echoes solemnly, sonorously, like a hymn, and is then mysteriously silenced,” Respighi wrote. His command of orchestral color is combined with an unerring sense for structuring a climax.

The Janiculum Hill, located just outside the boundaries of ancient Rome, offers sweeping views over the city. Its pines inspire a nocturne of hushed lyricism, featuring a solo clarinet, a glowing piano cadenza, and—most striking of all—the singing of a nightingale. In a remarkable innovation without precedent in the concert hall, Respighi calls for a phonograph recording of an actual nightingale’s song to be played alongside the live orchestra—an early and poetic anticipation of multimedia in the concert hall.

Set to a stirring martial tempo, the final movement is devoted to the “Pines of the Appian Way” and leads from the full moon imagined in the previous movement to a “misty dawn” over the “tragic country,” where soldier-like solitary pines guard the grand military avenue that symbolized and ensured Roman power. “Indistinctly, incessantly, the rhythm of unending steps,” as the composer put it. “The poet has a fantastic vision of past glories. Trumpets blare, and the army of the Consul bursts forth in the grandeur of a newly risen sun toward the Sacred Way, mounting the Capitoline Hill in triumph.”

—Thomas May

About the Artists

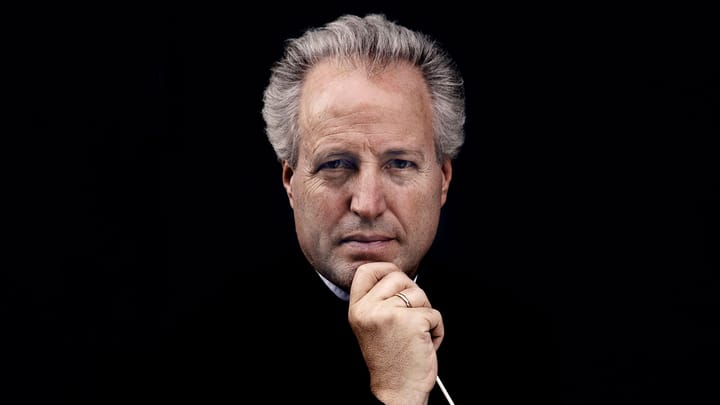

Jaap van Zweden

Jaap van Zweden is music director of the Seoul Philharmonic and music director designate of Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. Among his past music directorships are the New York Philharmonic, where his tenure included 31 premieres and the reopening of David Geffen Hall, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which was named Gramophone’s Orchestra of the Year under his leadership. He has conducted the Vienna Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Berlin Staatskapelle, London Symphony, Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among many others. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in October 2012 and will lead the Orchestra in a three-season cycle of Beethoven’s nine symphonies beginning in February 2026.

This season, van Zweden undertakes European and Asian tours with Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and rejoins the Royal Concert-gebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, and Antwerp Symphony, where he is conductor emeritus. In the United States, he returns to the Chicago Symphony and leads his first US tour with the Seoul Philharmonic. In Asia, he returns to the NHK Symphony Orchestra and the Hong Kong Philharmonic.

Van Zweden’s discography includes acclaimed releases on Decca Gold and Naxos. With the New York Philharmonic, he recorded David Lang’s prisoner of the state and Julia Wolfe’s Grammy-nominated Fire in my mouth. With the Hong Kong Philharmonic, he conducted the first full Ring cycle ever staged in Hong Kong, and his performance of Parsifal received the 2012 Edison Award for Best Opera Recording.

Born in Amsterdam, van Zweden was appointed the youngest-ever concertmaster of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at age 19, and began his conducting career in 1996. A winner of the Concertgebouw Prize and Musical America’s 2012 Conductor of the Year, he founded the Papageno Foundation with his wife, supporting young people with autism through music, housing, research, and innovation.

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang is celebrated for her charismatic artistry, emotional honesty, and captivating stage presence. She has performed with the world’s most venerated conductors, musicians, and ensembles, and is renowned not only for her virtuosity, but her spontaneous and lively performances.

Recent highlights include a European and South American play-direct tour with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, where she has been artist in residence, as well as her return to the United States where she is in residence with the New York Philharmonic. Her skill and charisma were demonstrated in a marathon Rachmaninoff performance at Carnegie Hall with the Philadelphia Orchestra, including all four of his concertos plus the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. In 2022, she gave the world premiere of Magnus Lindberg’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the San Francisco Symphony.

Wang was born into a musical family and began studying the piano at the age of six. She received advanced training in Canada and at the Curtis Institute of Music with Gary Graffman. Her international breakthrough came in 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich as soloist with the Boston Symphony. Two years later, she signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon and has since established her place among the world’s leading artists, with a succession of critically acclaimed performances and albums. Her recordings have garnered multiple awards, including five Grammy nominations and her first Grammy win for Best Classical Instrumental Solo with her 2023 release The American Project. For this she also won an Opus Klassik award in the concerto category.

As a chamber musician, Wang has developed long-lasting partnerships with several leading artists. She recently embarked on an international duo recital tour with pianist Víkingur Ólafsson. In addition to tonight’s SF Symphony Opening Gala, she opens Carnegie Hall’s season next month. Wang made her San Francisco Symphony debut in February 2006 and became a Shenson Young Artist later that year. She will return to Davies Symphony Hall next April for a Great Performers Series concert with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

Print Edition