In This Program

- The Concert

- At a Glance

- Program Notes

- Alban Berg: Seven Early Songs

- About the Artists

- About San Francisco Symphony

The Concert

Friday, September 26, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, September 27, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, September 28, 2025, at 2:00pm

Preconcert Talk with David H. Miller, UC Berkeley Department of Music

On stage Friday and Saturday at 6:30pm, Sunday at 1:00pm

Donald Runnicles conducting

Alban Berg

Seven Early Songs (1908, orch. 1928)

Nacht (Night)

Schilflied (Reed Song)

Die Nachtigall (The Nightingale)

Traumgekrönt (Dream-Crowned)

Im Zimmer (In the Room)

Liebesode (Love Ode)

Sommertage (Summer Days)

Irene Roberts mezzo-soprano

Intermission

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 1 in D major (1888, rev. 1906)

Langsam. Schleppend. (Slow. Dragging.)

Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (With powerful movement, but not too fast)

Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen (Solemn and measured, without dragging)

Stürmisch bewegt (With violent movement)

Irene Roberts’s performance is made possible through the generosity of the Mrs. Geoge J. Otto Memorial Vocalist Fund.

Preconcert talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half of the program is Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, which Mahler labored over and frequently revised over a period of years. In the end, it established his distinctive orchestral style and set him on course to be the last great Romantic symphonist.

Mahler, Berg, and Fin-de-siècle Vienna

May 16, 1906. Gustav Mahler, principal conductor of the Vienna Court Opera, is in Graz with his wife Alma to see the Austrian premiere of Salome, Richard Strauss’s incendiary new opera. Mahler, who had previously played and sung through the score with Strauss in a piano shop in Strasbourg—to the amazement of passers-by, who pressed their faces to the window in an attempt to hear what was happening—already considers Salome to be a work of genius. He had tried to secure the premiere for Vienna, but the imperial censors had shut down his proposal, balking at Strauss’s depictions of biblical characters expressing incestuous lust and committing acts of extreme violence. Mahler had been furious, so much so that he began hinting that his tenure at the Court Opera might be coming to an end. In a letter to Strauss, he had written, “You would not believe how vexatious this matter has been for me, or (between ourselves) what consequences it may have for me.” But where the city of Vienna had seen only difficulty, Graz had recognized an opportunity. And so, the much smaller provincial capital has taken a chance on Salome—and the bet has paid off. The city is heaving. The hotels are full to bursting; the public houses are abuzz with chatter about the work; the three-night run has more than sold out.

As the sun begins to set, Mahler and Strauss travel to the opera house together. The lobby is already packed. Somewhere in this crowd is 21-year-old composition student Alban Berg, who has travelled to Graz from Vienna in the company of his teacher Arnold Schoenberg, along with five of Schoenberg’s other apprentices. Berg would later tell friends about the “feverish impatience and boundless excitement” that he and his company all felt as the performance drew near. The crowd files expectantly into the auditorium, Strauss strides to the podium, the curtain goes up—and when the show is finished, the crowd erupts in exultant praise. As Strauss would later tell his wife Pauline, who had stayed at home in Berlin, the ovation lasted a full 10 minutes, stopping only when the fire curtain came down.

On the train back to Vienna, as Alma later recounted, Mahler’s head was still spinning. He was at a loss to understand how a work as challenging and brilliant as Salome should be met with rapturous acclaim by the general public. Mahler was convinced that genius and popularity were incompatible: this, at least, had been the lesson of his fraught tenure at the helm of the Vienna Court Opera. We tend to view fin-de-siècle Vienna as an enlightened, open-minded city, eager to cast off the shackles of tradition in pursuit of new artistic ideas—but while some Viennese did match this description (Schoenberg and Berg, to mention two), the reality was that many did not. Mahler’s failed bid to stage Salome hadn’t been the first new idea of his to be met with resistance by conservative factions in Vienna. His production of Smetana’s Czech nationalist opera Dalibor, in which the finale is rejigged to leave the hero alive, had caused outrage: extremist Viennese German nationalists had accused Mahler of “fraternizing with the anti-dynastic, inferior Czech nation.” Even Mahler’s own music—which, with its deep Romanticism, was far more palatable to a conservative ear than some other new music of the time—presented a problem in the eyes of the Viennese press: far from encouraging Mahler’s composition projects, the papers excoriated him for (as they saw it) neglecting his duties to the Opera in order to conduct his own music elsewhere. In 1907, this criticism reached fever pitch. Mahler resigned his post, leaving Vienna for New York. Four years later, he was dead.

Seven Early Songs

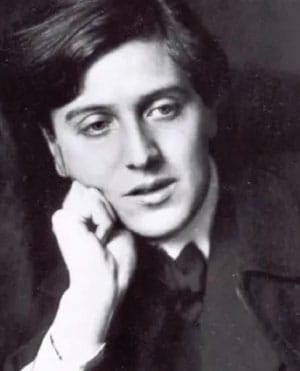

Alban Berg

Born: February 9, 1885, in Vienna

Died: December 24, 1935, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1905–08 (orch. 1928)

SF Symphony Performances: First—May 1995. Herbert Blomstedt conducted with Solveig Kringelborn as soloist. Most recent—November 2018. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Susanna Phillips as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo voice (soprano or mezzo-soprano), 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 1 trumpet, 2 trombones, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, snare drum, and bass drum), harp, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 16 minutes

Fast forward just over 20 years, to 1928. Times have changed. The horrors of the First World War have cast the earnest raptures of late Romanticism, as embodied by Mahler’s music in particular, in a dubious light. It is in this new, more bracing cultural atmosphere that Alban Berg, the wide-eyed neophyte who had been so dazzled by Salome, has surged to prominence on the Viennese musical scene. His opera, Wozzeck—a clear-eyed depiction of the callousness and sadism of military life that is as musically exhilarating as it is brutal—had been a sensation at its Berlin premiere three years before, and had shown in no uncertain terms that Berg was a composer to be reckoned with.

The path to recognition hadn’t been smooth for Berg. When he began his studies with Schoenberg in 1905, Berg had been an ardent writer of songs—but Schoenberg had seen this as an affliction to be cured. As Schoenberg later wrote, “In the condition in which [Berg] came to me, it was impossible for him to imagine composing anything but songs… He was incapable of writing an instrumental movement, of finding an instrumental theme… I corrected the deficiency.”

But now, with Wozzeck having firmly established his bona fides, Berg is free to return to the songs he had been writing 20 years before, when he took that exhilarating trip to Graz in the early days of his apprenticeship to Schoenberg. He selects seven of these, revises them for high voice (having previously written them for medium voice and piano), and gives them a lush, subtle orchestration that clearly expresses his own indebtedness to, and admiration of, the music of Mahler and Strauss in particular. The result is Seven Early Songs, wherein Berg shows that the fundamental elements of Mahler’s musical language—the surging climaxes, the ever-present longing, the sheer beauty of the sound—are not after all incompatible with the unease of 1920s Vienna. Even in an austere climate like that of the interwar years, with its swirling currents of doubt, anxiety, and feelings of impending disaster, the heart continues to want what it wants.

The Music

With the first ambiguous stirrings of “Nacht” (Night), we find ourselves in darkness, unsure of our footing. The soprano sings, “Clouds darken over night and the valley” as pizzicato strings tiptoe through a dense orchestral undergrowth. A glorious melodic flourish on “A distant wonderland opens” arrives like a shaft of moonlight piercing the cloud, a shining moment of Mahlerian ecstasy. Throughout, the sense of a tonal center comes and goes, as though glimpsed through shifting veils of mist. A more subdued mood characterizes “Schilflied” (Song of the Reed), whose softly swaying waltz rhythms evoke the movement of reeds by a pond. The orchestral colors swirl gently around the voice as she sings of seeming to hear her lover’s voice, first in the air, then in the rippling of the pond, as though he is drowning in the still water.

The wind sections fall silent for “Die Nachtigall” (The Nightingale), whose flowing string accompaniment and traditional A-B-A structure are reminiscent of Brahms. The lyrics summon images of a woman wandering in the heat of the sun, lost in thought, holding her summer hat in her hand. The wind section returns in “Traumgekrönt” (Dream-Crowned), a setting of a Rainer Maria Rilke poem, whose opening imagery of white chrysanthemums and bright sunshine immediately gives way to something much darker: a dead lover coming in a dream to take the sleeper’s soul. The languorous movement of the opening measures evoking the drowsy confusion of the central character. The orchestra accelerates slightly, falters, and then swells to another Technicolor bloom of Mahlerian rapture as the soprano sings, “Then you came deep in the night / to take my soul.” The shifting time signatures heighten the nebulous, dreamlike atmosphere.

“Im Zimmer” (In the Room) finds two lovers resting together by the fireside on an Autumn evening. Pizzicato strings suggest the dancing flames as the soprano sings, “A small red fire / crackles in the oven.” The tempo ebbs and flows in gentle sighs as the soprano tells of her tranquil happiness. The blissful mood continues into “Liebesode” (Love Ode), as great washes of dense harmony echo the swells of feeling expressed in the lyrics: “Dreams of ecstasy, filled with yearning.” “Sommertage” (Summer Days) brings a sense of greater urgency, and the song cycle comes to a close with a cymbal crash punctuating the ecstatic final cadence.

Symphony No. 1 in D major

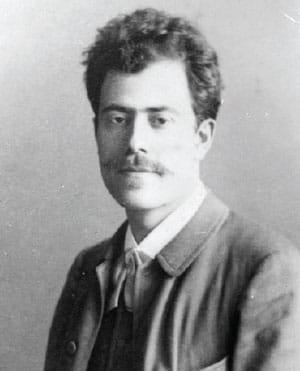

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1885–88 (rev. 1906)

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1921. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—January 2022. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 4 flutes (2nd, 3rd, and 4th doubling piccolos), 4 oboes (3rd doubling English horn), 4 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet and E-flat clarinet and 4th doubling 2nd E-flat clarinet), 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), 7 horns, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani (2 players), percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 50 minutes

In Berg’s Seven Early Songs, we see Romanticism through a glass darkly, as it were: it comes to us refracted by the lens of 1920s modernism. But in Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, we see Romanticism unfiltered. Completed in the winter of 1887–88, while Mahler was second conductor at the Leipzig Opera, the work’s dramatic character places it firmly within the Romantic tradition: Mahler conceived the whole symphony as a hero triumphing over forces that threaten to annihilate him. Though the work received a mixed response at its premiere (held in Budapest in 1889), it has come to be regarded as one of the most impressive and audacious first symphonies ever written. The work bears many of what would turn out to be Mahler’s stylistic hallmarks: a vast orchestral palette, the incorporation of folk music, allusions to extramusical sources (the work was initially inspired by Jean Paul’s novel Titan, though Mahler later downplayed the connection), and rich musical depictions of the natural world.

The Music

The first movement begins with an almost inaudible A-natural, spread over seven octaves. The harmonics played by the divided strings create the impression that the music is enveloped in a haze. Against this brumous backdrop, little melodic fragments evocative of cuckoo calls begin to stir, evoking the awakening of nature at dawn. Military signals and tattoos begin to sound from afar to welcome the new day. (The reveille is initially given to the clarinet rather than to the trumpet: the clarinet’s mellower timbre creates the impression of distance.) After a prolonged introduction, the first theme enters softly on cellos: this merry melody is a direct quote from “I went this morning over the field,” the second song from Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer cycle. The theme is passed through the orchestra, growing as it goes, before eventually being played by the entire brass section. Elements of the introduction follow—the sustained A returns, as do the clarinet’s cuckoo calls—before a new fanfare on French horn heralds the recapitulation. Again the momentum builds, and the movement comes to a close brimming with youthful exuberance.

The atmosphere of rural joy continues into the second movement, a modified minuet and trio, with the minuet replaced by a Ländler. The Ländler—a partner dance in triple time that traditionally featured hopping and stamping—was a more bucolic, and rather more raucous, precursor of the waltz. The tempo waxes and wanes a little as the theme moves around the orchestra, suggesting the humor and (perhaps) mild inebriation of peasants at their revels. The trio section is more meditative in tone: the tempo is slower and more measured, the tone more refined. One is put in mind of the hero having stepped out of the village hall for a breather, thinking perhaps of a different, more refined kind of life. A modified version of the Ländler theme returns, and the movement ends in happy chaos.

The transition to the third movement is abrupt and unexpected. Such sudden changes in mood and texture would, in later works, be revealed as emblematic of Mahler’s symphonic style. The opening melody here is the familiar folk tune Frère Jacques (which Mahler knew as “Bruder Jakob”), played in a minor key, and scored—most unusually for the time—for solo double bass. The ensuing funeral march was inspired by Moritz von Schwind’s woodcut The Hunter’s Funeral, well-known to Austrian children in Mahler’s day, in which a procession of animals bear a dead hunter to his grave. There is, of course, a deep irony to the solemnity of this ritual: the animals should surely be celebrating the demise of the hunter, not mourning his passing. This latent irony becomes more explicit as the funeral march slows to a stop, allowing what sounds like a klezmer band to saunter insouciantly through the procession. The march resumes briefly, before being interrupted again by a more contemplative section, featuring elements from the fourth song in Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer. Finally, Mahler puts all three elements on top of each other; the texture gradually falls apart, and the movement ends in uneasy silence.

The hush is broken by a jump-scare, as with a hair-raising shriek, the final movement begins. This is the most musically complex and extended movement, incorporating several elements from the beginning of the symphony. The strings whirl and dive overhead as fragments of a theme in F minor appear in the brass, before being taken up by the majority of the wind section. A lyrical theme in the strings eventually calms the storm—but the opening brass fragments reappear, and the energy begins once more to accumulate, as though heading to a climax. Mahler diverts the music here, however, and the momentum wanes again as more quotes from the first movement appear. Eventually, an expansive brass fanfare emerges from the orchestra like a beam of light, and the symphony comes to a triumphant, exultant close.

—Jenny Judge

Alban Berg: Seven Early Songs

Nacht

Dämmern Wolken über Nacht und Tal,

Nebel schweben, Wasser rauschen sacht.

Nun entschleiert sich’s mit einemmal:

O gib acht! Gib acht!

Weites Wunderland ist aufgetan.

Silbern ragen Berge traumhaft gross,

Stille Pfade silberlicht talan

Aus verborgnem Schoss;

Und die hehre Welt so traumhaft rein.

Stummer Buchenbaum am Wege steht

Schattenschwarz, ein Hauch vom fernen Hain

Einsam leise weht.

Und aus tiefen Grundes Düsterheit

Blinken Lichter auf in stummer Nacht.

Trinke Seele! Trinke Einsamkeit!

O gib acht! Gib acht!

—Carl Hauptmann (1858–1921)

Night

Clouds darken over night and the valley,

mists drift, waters murmur.

Suddenly, it is unveiled.

Give heed! Give heed!

A distant wonderland opens.

Silver mountains rise, huge as in a dream,

silent paths, silver-lit,

head from the valley’s hidden bosom;

And the world is sublime, pure as in a dream.

A silent beech tree stands along the way,

dark as a shadow. A lonely breath from the distant grove

stirs softly.

And from the canyon’s deep gloom

lights begin to twinkle in the mute night.

Drink, oh soul! Drink solitude!

Give heed! Give heed!

Schilflied

Auf geheimem Waldespfade

Schleich’ ich gern im Abendschein

An das ode Schilfgestade,

Mädchen, und gedenke dein!

Wenn sich dann der Busch verdüstert,

Rauscht das Rohr geheimnisvoll,

Und es klaget und es flüstert

Dass ich weinen, weinen soll.

Und ich mein’, ich höre wehen

Leise deiner Stimme Klang,

Und im Weiher untergehen

Deinen lieblichen Gesang.

—Nicolaus Lenau (1802–50)

Reed Song

On a hidden forest path

I like to steal away in the evening glow

along the desolate reedy shore,

my girl, and think of you!

When the trees darken,

the reeds murmur their secrets,

lamenting and whispering,

so that I want to weep.

And I think I hear

The soft sound of your voice,

and your lovely song

sinking in the pond.

Die Nachtigall

Das macht, es hat die Nachtigall

Die ganze Nacht gesungen;

Da sind von ihrem süssen Schall,

Da sind in Hall und Widerhall

Die Rosen aufgesprungen.

Sie war doch sonst ein wildes Blut;

Nun geht sie tief in Sinnen,

Trägt in der Hand den Sommerhut

Und duldet still der Sonne Glut,

Und weiss nicht, was beginnen.

Das macht, es hat die Nachtigall

Die ganze Nacht gesungen;

Da sind von ihrem süssen Schall,

Da sind in Hall und Widerhall

Die Rosen aufgesprungen.

—Theodor Storm (1817–88)

The Nightingale

It’s because the nightingale

has sung throughout the night;

the sweetness of her sound,

pealing and echoing,

made the roses bloom.

She had always been so wild.

Now she is thoughtful,

carries her summer hat in hand

and bears the summer heat

and knows not where to begin.

It’s because the nightingale

has sung throughout the night;

the sweetness of her sound,

pealing and echoing,

made the roses bloom.

Traumgekrönt

Das war der Tag der weissen Chrysanthemen,

Mir bangte fast vor seiner Pracht . . .

Un dann, dann kamst du mir die Seele nehmen

Tief in der Nacht . . . . .

Mir war so bang, und du kamst lieb und leise,

Ich hatte grad’ im Traum an Dich gedacht.

Du kamst — und leis wie eine Märchenweise

erklang die Nacht . . . . .

—Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926)

Dream-Crowned

It was the day of the white chrysanthemums,

their glory was almost frightening.

And then, then you came deep in the night

to take my soul.

I was so afraid, and you came, beautiful and quiet.

I had just been dreaming of you.

You came, and the night was filled with

the soft sound of a fairy-tale song.

Im Zimmer

Herbstsonnenschein.

Der liebe Abend blickt so still herein.

Ein Feuerlein rot

Knistert im Ofenloch und loht.

So! — Mein kopf auf deinen Knie’n. —

So ist mir gut;

Wenn mein Auge so in deinem ruht.

Wie leise die Minuten zieh’n! . . .

—Johannes Schlaf (1862–1941)

In the Room

Autumn sunshine.

The dear evening looks in so calmly.

A small red fire

crackles in the oven.

So! My head on your knee,

and all is well.

While my gaze rests in yours,

how quietly the minutes pass.

Liebesode

Im Arm der Liebe schliefen wir selig ein.

Am offnen Fenster lauschte der Sommerwind,

und unserer Atemzüge Frieden

trug er hinaus in die helle Mondnacht. —

Und aus dem Garten tastete zagend sich

ein Rosenduft an unserer Liebe Bett

und gab uns wundervolle Träume,

Träume des Rausches — so reich an Sehnsucht.

—Otto Erich Hartleben (1864–1905)

Love Ode

Happily, we fell asleep in the arms of love.

The summer wind listened at the open window

and drew our peaceful breaths out

into the bright moonlit night.

And from the garden the scent of roses

made its wavering way to our bed of love

and gave us wonderful dreams.

Dreams of ecstasy, filled with yearning.

Sommertage

Nun ziehen Tage über die Welt,

gesandt aus blauer Ewigkeit,

Im Sommerwind verweht die Zeit.

Nun windet nächtens der Herr

Sternenkränze mit seliger Hand

über Wander- und Wunderland.

O Herz, was kann in diesen Tagen

dein hellstes Wanderlied denn sagen

von deiner tiefen, tiefen Lust:

Im Wiesensang verstummt die Brust,

nun schweigt das Wort, wo Bild um Bild

zu dir zieht und dich ganz erfüllt.

—Paul Hohenberg (1885–1956)

Summer Days

Now days pass over the world,

sent out of blue eternity.

Time passes in the summer wind.

At night, the Lord

winds starry garlands happily

over wander- and wonderlands.

Oh heart, these days

what can your brightest wander-song say

about your deep, deep happiness?

The breast falls silent as the meadows sing.

Words fail as image after image

appears before you and fills you.

Translations: Larry Rothe

About the Artists

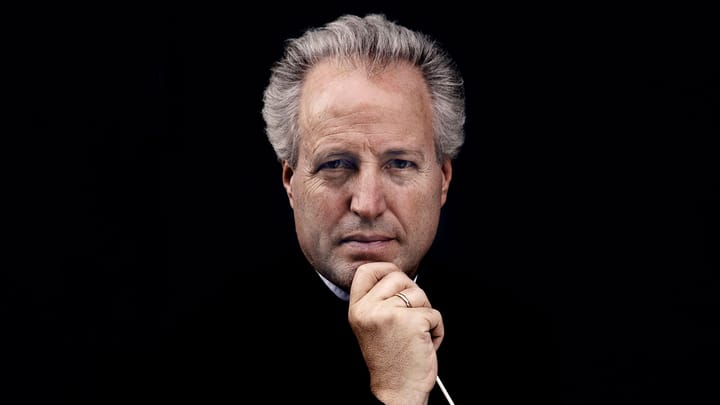

Donald Runnicles

Over a career spanning 45 years, Donald Runnicles has built his reputation on enduring relationships with several of the world’s most significant opera companies and orchestras. He is especially celebrated for his interpretations of the Romantic and post-Romantic repertoire which are core to his musical identity.

The 2025–26 season marks both his final season as music director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin as well as his first season as chief conductor of the Dresden Philharmonic. He also continues to serve as music director of the Grand Teton Music Festival and as principal guest conductor of the Sydney Symphony. Highlights this season include a 10-city tour to Asia with the Dresden Philharmonic; new productions at the Deutsche Oper of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and Korngold’s Violanta, along with two cycles of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen in a Stefan Herheim production that he premiered with the company; and guest engagements with the BBC Scottish Symphony in Mahler’s Second Symphony, and his debut with the Philharmonia Orchestra in Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony.

Runnicles’s chief artistic leadership roles have included the San Francisco Opera from 1992 to 2008, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra from 2009 to 2016, and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s from 2001 to 2007. He was also principal guest conductor of the Atlanta Symphony from 2001 to 2023.

Born and raised in Edinburgh, Scotland, Runnicles was appointed OBE in 2004, and was made a Knight Bachelor in 2020. He holds honorary degrees from the University of Edinburgh, the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in January 1995.

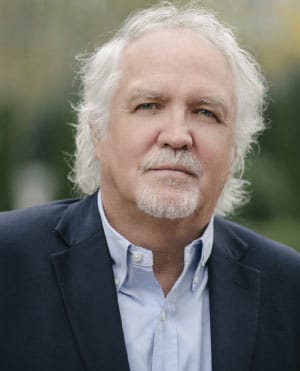

Irene Roberts

This season, Irene Roberts makes her role debut as Sieglinde in Die Walküre in Munich, appears as Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde and Kundry in Parsifal at Deutsche Oper Berlin, and also sings Brangäne in Amsterdam and Wiesbaden. Last season she appeared at San Francisco Opera as Offred in The Hand-maid’s Tale and returned to Deutsche Oper Berlin as Brangäne, Carmen, and in her role debut as Eboli in Don Carlo. Other recent highlights include a highly praised debut as Kundry at the Bavarian State Opera and as Venus in Tannhäuser at the Bayreuth Festival.

Guest appearances have taken her to opera houses in Hanover, Palermo, Venice, Tokyo, Lyon, Atlanta, the Macerata Opera Festival, and the Metropolitan Opera. On the concert stage, she has performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre National d’Île-de-France, Orchestra Sinfonica Siciliana, and Swedish Radio Symphony. She makes her San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

From 2015 to 2024, Roberts was a member of the ensemble at Deutsche Oper Berlin, where she built a versatile repertoire spanning Mozart, Rossini, Offenbach, Strauss, Wagner, and contemporary opera. Prior to that, she was a member of Palm Beach Opera’s Young Artist Program and a winner of its vocal competition. A native of Sacramento, California, she studied voice at the University of the Pacific and the Cleveland Institute of Music.

David H. Miller is an assistant professor of practice in music and American studies at UC Berkeley. His research focuses on modernist music, particularly that of Anton Webern, and its performance and reception in the United States. At Cal, he has taught courses on J.S. Bach, interwar American music, and postwar American experimentalism. As a performer, he focuses on Baroque double bass and viola da gamba, and directs the University Baroque Ensemble. He holds a BA in music from Harvard University and a PhD in musicology from Cornell University.