In This Program

- The Concert

- At a Glance

- Program Notes

- Text and Translation

- About the Artists

- About San Francisco Symphony

The Concert

Thursday, June 12, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, June 13, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, June 14, 2025, at 7:30pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 2 in C minor (1894)

Allegro maestoso

Andante moderato

In ruhig fliessender Bewegung (In quietly flowing motion)

Urlicht (Primal Light)

Im Tempo des Scherzos (In the tempo of the Scherzo)

Heidi Stober soprano

Sasha Cooke mezzo-soprano

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

This program is performed without intermission.

Lead support for the San Francisco Symphony Chorus this season is provided through a visionary gift from an anonymous donor.

Sasha Cooke’s and Heidi Stober’s performances are generously sponsored by Anderson Norby.

Program Notes

At a Glance

The fourth movement introduces a mezzo-soprano to sing Urlicht (Primal Light), based on Des Knaben Wunderhorn (a collection of German folk poems), and the fifth movement adds a soprano and chorus for a setting of a hymn by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, elaborated on by Mahler himself.

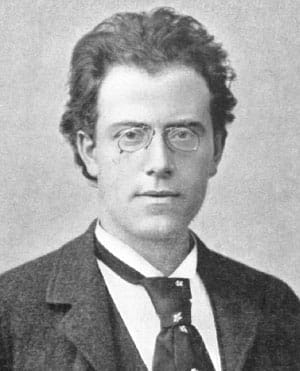

Symphony No. 2 in C minor

Gustav Mahler

Born: July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, Bohemia

Died: May 18, 1911, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1888–94

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1924. Alfred Hertz conducted with Claire Dux and Merle Alcock as soloists and the Spring Festival Chorus. Most recent—October 2022. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted with Golda Schultz and Michelle DeYoung as soloists and the San Francisco Symphony Chorus.

Instrumentation: soprano and alto (mezzo-soprano) soloists, chorus, 4 flutes (doubling piccolos), 3 oboes (3rd doubling 2nd English horn), English horn, 4 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet and 4th doubling 2nd E-flat clarinet), E-flat clarinet, 4 bassoons (4th doubling contrabassoon), 11 horns (4 offstage), 8 trumpets (4 sometimes offstage), 4 trombones, tuba, timpani (2 players), percussion (triangle, cymbals, bells, chimes, tam-tam, snare drum, and bass drum), 2 harps, organ, and strings

Duration: About 80 minutes

In one sense, death is the most familiar thing in the world. It comes at us sidelong almost every day in the news: the deaths of public figures, the victims of crime, the numbered casualties of war. More rarely, it makes a full frontal assault in the form of the death of someone we love. And finally, of course, it comes for us.

We know all of this. Death and taxes, as the old quip goes: the only certainties in life. And yet for all its familiarity, there is something so monstrous, so wrong about death as to render it almost unthinkable. The moment when a loved one dies—when they go from being there to not being there; when their body suddenly becomes just that, a mere thing among things; when their belongings, previously given meaning and unity by the life at their center, are abruptly revealed as so much random junk—is felt as a rupture in the fabric of your world. And your own death: well. It’s hard to know how to even begin to think about that. So many of us don’t. To have the knowledge break over you like a fever that not just you, nor just the ones you love, but almost everyone currently living on earth will be in the ground a hundred years from now is to realize that most of the time, we live as though we were immortal.

Not Gustav Mahler, though. Mahler was never allowed to forget either his own mortality, or that of those closest to him. He was the second of 14 children; the first, a boy named Isidor, died in infancy. When Mahler was not yet 15, his younger brother Ernst died of a long illness, a loss that marked Mahler deeply. (In the end, only five of his 13 siblings would live past childhood.) Mahler, who was already something of a musical wunderkind at this point, set about expressing the weight of his grief through music. Though the opera he began drafting in memory of his brother has not survived, music would remain for Mahler a mirror in which he could confront the horrors of death. In his colossal Second Symphony, Mahler presents a feature-length musical depiction of the paradoxes of living in the shadow of mortality. In the music, we encounter death now as scourge, now as salvation: as both the source of our deepest pain, and the ultimate relief from it. We see death as an unstoppable, ungovernable force; we see too the rituals by means of which we seek to domesticate that force. We see the unfairness of a world in which the best of us perish and the worst survive, and at the same time, we see death as the supreme democratic power, the one playing field where beggar and king can meet as equals.

Mahler began what would become the first movement of his Second Symphony in 1888. He initially conceived this as a single-movement symphonic poem called Todtenfeier (Funeral Rites) illustrating the funeral of the hero of his First Symphony. From the beginning, Mahler appears to have considered that Todtenfeier might in fact be destined to be the first movement of a symphony—the early sketches of the second movement also date from 1888—but he wavered on this for five years, eventually composing most of the material for the remaining movements in 1893. But even then, Mahler was unsure about the symphony project. His mentor Hans von Bülow had hated Todtenfeier, for one thing: when Mahler played the piano reduction to him in 1891, von Bülow reportedly covered his ears in protest, saying, “If what I have just heard is music, I understand nothing about music.” And for another, Mahler couldn’t come up with a suitable finale. It wasn’t until von Bülow’s funeral in 1894 that inspiration suddenly struck. (That the dislodging of Mahler’s creative block should have coincided with the demise of a revered but critical advisor would, one suspects, not be surprising to a psychoanalyst.) Describing this moment, Mahler wrote: “Then the choir, up in the organ-loft, intoned Klopstock’s Resurrection chorale. It flashed on me like lightning, and everything became plain and clear in my mind! It was the flash that all creative artists wait for—‘conceiving by the Holy Ghost!’” He got to work immediately. The symphony premiered the following year, in 1895, with Mahler himself at the podium of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Mahler was deeply ambivalent about the value of programs that describe music in terms of a story that it purportedly tells. In a program that he wrote for a performance of the Second Symphony, he himself gave such a narrative description of the music, before dismissing what he’d just written as “a crutch for a cripple.” He went on: “It gives only a superficial indication, all that any program can do for a musical work, let alone this one, which is so much all of a piece that it can no more be explained than the world itself.” At most, he thought, programs should seek precisely to describe not the narrative content supposedly possessed by the music, but the feeling being expressed by it. And yet, Mahler was again and again compelled to set out in words the story of the Second Symphony in particular. Of the first movement, he wrote:

We stand by the coffin of a well-loved person. His life, struggles, passions and aspirations once more, for the last time, pass before our mind’s eye. And now in this moment of gravity and emotion which convulses our deepest being. . . our heart is gripped by a dreadfully serious voice. . .

What now? What is this life—and this death? Do we have an existence beyond it? Is all this only a confused dream, or do life and this death have a meaning?

We must, thought Mahler, attempt to answer this question if we are to live on—and the Symphony itself presents an answer to it, in the form of the massive finale the outlines of which Mahler had glimpsed at von Bülow’s funeral. This is a vivid, and frankly terrifying, musical depiction of the Last Judgment: a titanic struggle against death itself that culminates in an ecstatic, exhilarating moment of transcendence. We can all be redeemed, Mahler is saying: all of us, not just the rich, nor just the powerful, nor even just those who dedicate themselves to virtue and sobriety. Every one of us can get to heaven. But we have to go through hell first.

The Music

The first movement (Allegro maestoso) bristles to life with a fearful shudder on tremolo strings. Almost immediately, the cellos and basses erupt. The ensuing stampede is eventually quelled by the oboe, entering with the movement’s first theme. Mahler sets this melody low in the oboe’s register, which gives it a muted, constricted quality. The fragility of the oboe’s composure is further highlighted by the rumblings of the lower strings which, one feels (and soon discovers), have been only temporarily tamed. When the second theme eventually arrives on high strings, we are transported to an entirely different place—here is bliss, peace, reconciliation—but it’s a false dawn, because the low strings burst once more into frenzied life, and the initial themes return in extended and developed form. The story of this movement is, in a sense, the funeral procession of the hero—but more than that, it’s the story of grief itself. For Mahler articulates, in precise and heartbreaking musical detail, the emotional turbulence of losing someone you love: the despair, the dread, the unquenchable longing; the merciful spells of serenity that arrive unbidden, and the hope that tentatively dawns in such moments; and inevitably, the resurgence of agonies that are all the more paralyzing for the stirrings of optimism that they quench.

The second movement (Andante moderato), a delicate, sweet Ländler that rarely raises its voice above a whisper, could hardly be more dissimilar to the first. Mahler described this movement as an intermezzo, “like an echo of long past days from the life of him whom we carried to the grave in the first movement, while the sun still smiled at him.” He was aware, however, that it might appear incongruous given the tumult of the first movement. And so, he stipulated that conductors should take a pause of five minutes between the end of the first movement and the beginning of the second, so that the audience should have time to adjust. Five minutes is a very long time in a silent concert hall—so much so that the pause Mahler requested is rarely observed in full today. Still, in a world where cinematic “jump cuts” between scenes of wildly contrasting character and mood are second nature to us, the need for the pause is arguably less stark than it was in Mahler’s day. And besides, the abrupt mood swing between first and second movements is in itself apt given the subject matter. As anyone who has lost a loved one knows, the suddenness and unpredictability with which such memories can assail one are part of what makes grief so destabilizing.

At the beginning of the third movement (In ruhig fliessender Bewegung), the scene changes yet again, and we are at the edge of a river where St. Anthony of Padua is preaching Christianity to the fish. There is a religious seriousness here, but a note of comedy, too, or even of farce. Mahler once joked that if the sinuous character of the music could express the movement of the river and the creatures it contained, it could also imply that St. Anthony was drunk, bobbing and weaving on the riverbank as he sermonized to the unheeding fish. It’s tempting to read this movement as a wry acknowledgment of the doubts that may plague even the most fervent religious believer. (After all, the religious are those that have faith—but having faith is in part a matter of acknowledging, however inchoately, that decisive proof is not on the cards.) And more particularly, one may well wonder what significance this note of religious doubt has, in light of what is to follow in the rest of the symphony. Perhaps Mahler is suggesting (however unconsciously) that the triumphant vision of universal redemption he will present in the finale may itself be a mere fantasy, borne of an inability to accept the finality of death.

However, the mood of ironic detachment is soon dispelled by the fourth movement (Urlicht), a solemn and heartfelt song in which the alto soloist pleads for relief from the suffering of life. The music leads without pause into the final movement (Im Tempo des Scherzos), in which the alto’s plea finds an answer. Echoes of themes presented in the previous movement recur, before the immense mass of the orchestra gathers itself for what Mahler described as the “march of the dead,” a vision of resurrected bodies advancing together in pursuit of eternal life. The choir enters, hushed at first but soon gaining in force and dramatic power; the alto and soprano soloists sing of the desire that suffering should not be in vain. An almost unbearable tension builds, which only finds complete resolution in the final moments of the symphony, as the tolling of church bells gives way to one last fortissimo flourish. The cumulative dramatic weight of this massive finale overwhelmed even Mahler himself. He wrote, “The increasing tension, working up to the final climax, is so tremendous that I don’t know myself, now that it is over, how I ever came to write it.”

—Jenny Judge

Text and Translation

Urlicht

O Röschen rot!

Der Mensch liegt in grösster Not!

Der Mensch liegt in grösster Pein!

Je lieber möcht’ ich im Himmel sein!

Da kam ich auf einen breiten Weg,

Da kam ein Engelein und wollt’ mich abweisen.

Ach nein! Ich liess mich nicht abweisen!

Ich bin von Gott und will wieder zu Gott!

Der liebe Gott wird mir ein Lichtchen geben,

Wird leuchten mir bis in das ewig selig Leben!

—from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Auferstehung

Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du,

Mein Staub, nach kurzer Ruh!

Unsterblich Leben! Unsterblich Leben

Wird der dich rief dir geben!

Wieder aufzublüh’n wirst du gesät!

Der Herr der Ernte geht

Und sammelt Garben

Uns ein, die starben!

—Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

O glaube, mein Herz, o glaube:

Es geht dir nichts verloren!

Dein ist, dein, ja dein, was du gesehnt!

Dein, was du geliebt, was du gestritten!

O glaube:

Du wardst nicht umsonst geboren!

Hast nicht umsonst gelebt, gelitten!

Was entstanden ist, das muss vergehen!

Was vergangen, auferstehen!

Hör auf zu beben!

Bereite dich zu leben!

O Schmerz! Du Alldurchdringer!

Dir bin ich entrungen!

O Tod! Du Allbezwinger!

Nun bist du bezwungen!

Mit Flügeln, die ich mir errungen,

In heissem Liebesstreben

Werd’ ich entschweben

zum Licht, zu dem kein Aug’ gedrungen!

Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben!

Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du,

Mein Herz, in einem Nu!

Was du geschlagen,

Zu Gott wird es dich tragen!

—Gustav Mahler

Primal Light

Oh, dearest red rose:

humankind suffers such privation,

humankind suffers such anguish,

that I would rather be in heaven.

As I came upon a wide-open path

a sweet angel came and wanted to turn me away.

But no, I would not let myself be turned away!

I am from God, and want to return to God.

The good Lord will give me a glimmering light

that will shine upon me into eternal blessed life!

Resurrection

Arise! Yes, you will arise

my dust—after a brief rest!

The one who called you forth

will give you immortal life.

You are sown to bloom again!

The lord of the harvest

gathers, like sheaves,

those who have died.

Believe, my heart, believe:

you shall lose nothing!

Yours, yes yours is what you longed for!

Yours: what you loved, what you fought for!

Indeed, believe:

You were not born in vain!

Nor have you lived or suffered in vain!

What has arisen, must pass away!

What has passed away, must arise!

Behold! Cease trembling!

Prepare yourself to live!

Anguish: you who pervades all,

from you I am wrested!

Death: you who conquers all,

now you are vanquished!

On wings I have gained

in fervent striving for love

I will soar toward that light

which no eye has seen beyond!

I will die, so to live!

Arise! Yes, you will arise

my heart—in a mere instant!

Through what you have wrought,

to God shall you be carried!

Translation: Noam Cook

© 2024

About the Artists

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

Read our Salonen feature “In Good Time,” SF Symphony Musicians’ Salonen remembrances, and more:

Heidi Stober

This season, Heidi Stober debuts at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, singing Gretel in Hansel und Gretel. She also appears at the Deutsche Oper Berlin as Zdenka in Arabella and as Pat Nixon in Nixon in China; at Semperoper Dresden as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; and in the title role of Thea Musgrave’s Mary, Queen of Scots with the English National Opera. In concert, she performs Mozart’s Requiem with the Musikkollegium Winterthur in Switzerland, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Indianapolis Symphony, and gives recitals at the Oxford International Song Festival, New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, and with the Collaborative Arts Institute of Chicago.

Stober’s operatic highlights include a long relationship with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, as well as multiple roles at the Metropolitan Opera and San Francisco Opera, where she most recently appeared as Blanche de la Force in Dialogues of the Carmelites and was a soloist at the 100th Anniversary Concert. She has also appeared with Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Santa Fe Opera, Opera Philadelphia, Hamburg State Opera, Vienna State Opera, Dutch National Opera, among other companies. In concert, she has performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Houston Symphony, Berlin Radio Symphony, and Grand Teton Music Festival. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut on New Year’s Eve 2012 and returns next December for Handel’s Messiah.

Originally from Waukesha, Wisconsin, Stober attended Lawrence University and New England Conservatory. She continued her professional training as a member of the Houston Grand Opera Studio and now resides in Berlin.

Sasha Cooke

Two-time Grammy Award–winning mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke has sung at the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, English National Opera, Seattle Opera, Opéra National de Bordeaux, and Gran Teatre del Liceu, among others, and with more than 80 symphony orchestras worldwide.

Cooke began the 2024–25 season with a return to the Bard Music Festival as Marguerite in La Damnation de Faust followed by Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde at the Gstaad Festival. On the operatic stage, she debuted at La Monnaie de Munt as Emilie Ekdahl in the world premiere of Mikael Karlsson and Royce Vavrek’s Fanny and Alexander, and returned to Houston Grand Opera in her role debut as Venus in Tannhäuser. On the concert stage, she appears this season with the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Vienna Radio Symphony, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Cologne Philharmonic, London Philharmonia, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and St. Louis Symphony.

Cooke made her San Francisco Symphony debut in June 2009 and became a Shenson Young Artist in January 2010. She toured Europe with Michael Tilson Thomas and the Symphony, premiered MTT’s Meditations on Rilke (captured on a Grammy-winning SFS Media release), and recorded two of MTT’s songs on Grace: The Music of Michael Tilson Thomas. She most recently appeared on MTT’s 80th Birthday Concert in April.

Cooke is a graduate of Rice University and the Juilliard School. She also attended the Music Academy of the West, Aspen Music Festival, Ravinia Festival’s Steans Music Institute, Wolf Trap Foundation, Marlboro Music Festival, and the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance. She has also prepared choruses for the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and Music Academy of the West.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011.

About the SF Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8), Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8), and most recently Best Opera Recording (for Saariaho’s Adriana Mater).

Lead support for the San Francisco Symphony Chorus this season is provided through a visionary gift from an anonymous donor.

To learn more about their generous gift, a new Chorus endowment, and ways to support it, please contact Jay Auslander, Director of Legacy Giving, at 415.503.5404 or jauslander@sfsymphony.org.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

SOPRANOS

Elaine Abigail

Naheed Attari

Sylvia V. Baba

Alexis Wong Baird

Arlene Boyd

Olivia T. Brown

Helen J. Burns

Laura Canavan

Sarita Nyasha Cannon

Rebecca Capriulo

Sara Chalk

Phoebe Chee*

Mun-Wai Chung

Francielle De Barros

Lauren Diez

Andrea Drummond

Tonia D’Amelio*

Elizabeth Emigh

Cara Gabrielson*

Tiffany Gao

Nina Groleger

Julia Hall

Elizabeth Heckmann

Hyun Suk Jang

Betsy Johnsmiller

Kate Juliana

Anna Keyta*

Jocelyn Queen Lambert

Becky Lau

Ellen Leslie*

Lane McKenna*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Diana Pray

Laura Stanfield Prichard

Bethany R. Procopio

Shroothi P. Ramesh

Hallie Randel

Kelly Ryer

Rebecca Shipan

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Sarah Vig

Lauren Wilbanks

ALTOS

Carolyn Alexander

Terry A. Alvord*

Emily Pantaleoni Bernier

Melissa Butcher

Celeste Camarena

Carol Copperud

Corty Fengler

Stacey L. Helley

Amy L. Hespenheide

Emily (Yixuan) Huang

Kelsey M. Ishimatsu Jacobson

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen Josaitis

Gretchen Klein

Katherine M. Lilly

Joyce Lin-Conrad

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Kimberly J. Orbik

Tiffany Ou-Ponticelli

Lindsay Marie Rader

Leandra Ramm*

Linda J. Randall

Meredith Riekse

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Kathryn Schumacher

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Sandy Sellin

Dr. Meghan Spyker*

Kyle S. Tingzon*

Mayo Tsuzuki

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

Hannah J. Wolf

TENORS

Paul Angelo

Carl A. Boe

Alexander P. Bonner

Todd Bradley

Seth Brenzel*

Dean Christman

Daniel J. Costa

Scott Dickerman

Thomas L. Ellison

Christian Emigh

Elliott JG Encarnación*

Patrick Fu

Ron Gallman

Kevin Gibbs*

Edward Im

Alec Jeong

Drew Kravin

James Lee

Benjamin Liupaogo*

Benjamin S. Lorenzoni

Andrew P. McIver

Jack O’Reilly

Ryan S. Peterson

David Kurtenbach Rivera*

Darita Seth*

Tetsuya Taura

Troy Turriate*

John A. Vlahides

David von Bargen

Nicholas Weininger

Jack Wilkins*

Weichen Winston Yin

John Paul Young

Jakob Zwiener

BASSES

Matthew Ahn

Simon Barrad*

Sean Brooks

Phil Buonadonna

Robert Calvert

Sean Casey

Adam Cole*

Noam Cook

James Radcliffe Cowing III

Malcolm Gaines

Rick Galbreath

Richard M. Glendening

Bradley A. Irving

Roderick Lowe

Tim Marson

Hugo Mendel

Richard Mix*

Clayton Moser*

Case Nafziger

Julian Nesbitt

Chengrui Pan

Bradley C. Parese

Jess Green Perry

Matthew C. Peterson*

Michael Prichard

Mark E. Rubin

Timothy Echavez Salaver

Chung-Wai Soong*

Storm K. Staley

Michael Taylor*

Connor Tench

David Varnum*

Julia Vetter

Goangshiuan Shawn Ying

Jenny Wong,

Chorus Director

John Wilson,

Rehearsal Accompanist

*Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists

FRIENDS OF THE CHORUS

The San Francisco Symphony gratefully acknowledges the following donors who have made a recent contribution of $100 or more to the San Francisco Symphony Chorus through March 28, 2025.

Ms. Lois Aldwin

Carolyn Alexander

Paul Angelo

Ms. Catherine Atcheson & Mr. Christian Fritze

Ms. Naheed Attari

Bruce Beron & Diane Wexler

Arlene Boyd

Seth Brenzel & Malcolm Gaines

Mr. Michael Coleman

Ms. Wendy Cook

David^ & Maggie Cooke♪

Carol Copperud

Dandelion/Tampopo

Ms. Paul M. Emmert

Ms. Susan M. Fandel

Corty & Alf Fengler

Sally Galway

Mr. Richard M. Glendening

Mr. James Haas

Mr. David Hammer

Michael A. Harrison & Susan Graham Harrison

Dr. Robert Haxo

Ms. Ashley Hecht

Ms. Amy L. Hespenheide

Mr. Robert Hicks

Michele Fromson

Elizabeth L. Hobson

Al Hoffman & David Shepherd

Mr. Robert Huber

Insperity, Inc.

Ms. Mary R. Jackman

Judith Jones

Ms. Ann Jorgensen

Cathleen Josaitis

The Keyes-Sulat Family Fund

Joyce Lin-Conrad & Mark Conrad

Yi & Chris Polczynski

Brian P. McCune

Mr. David Meders

Ms. Courtney Miller

Dr. Scott Mitchell & Dr. Vicki Coe

Mr. & Mrs. Robert Mueller

Mr. Kenneth R. Noyes

Mrs. Nancy Philippine

Mr. Karl Pribram

Dr. David R. Priest & Rev. Eric M. Nefstead

Nancy Reist

Ms. Julene S. Rhoan

Meredith Riekse & Jack Zepp

San Francisco Choral Music Fund

Ms. Nina D. Schwartz

Dr. Sandra C. Sellin

Ms. Jeanette Shinsako

Cherrill M. Spencer♪

Mrs. Karen Streicher

Tricia Swift

Tom & Rosemary Tisch

Dan & Lauren Wilkins

Ms. Arden Wong

Mr. Goangshiuan Shawn Ying

Anonymous (2)

♪Pierre Monteux Society member

^Deceased