In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, June 6, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, June 7, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, June 8, 2025, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Richard Strauss

Don Juan, Opus 20 (1888)

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 7 in C major, Opus 105 (1924)

Adagio–Vivacissimo–Adagio–Allegro moderato–Adagio

Intermission

Gabriella Smith

Rewilding (2025)

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Richard Strauss

Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Opus 28 (1895)

This concert is presented in partnership with

Lead support for these performances of Gabriella Smith’s Rewilding is provided by the Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for New Works of Music.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Jean Sibelius’s one-movement Symphony No. 7 is relatively brief, but structurally complex and hugely concentrated in effect. It was his last symphony—while other composers ended their symphonic careers with ever-grander works, Sibelius grew more austere.

Gabriella Smith’s Rewilding is a San Francisco Symphony commission and world premiere, inspired by the composer’s climate activism and work restoring natural ecosystems. Listen for how the orchestra creates the sounds of a frog chorus, insects, and bicycle wheels.

Don Juan, Opus 20

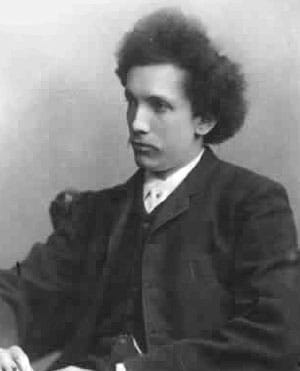

Richard Strauss

Born: June 11, 1864, in Munich

Died: September 8, 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany

Work Composed: 1888–89

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1912. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—April 2024. Karina Canellakis conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbal, and bells), harp, and strings

Duration: About 18 mins

The genre of the symphonic poem was molded into its classic form by Franz Liszt, who released a stream of them in the 1840s and ’50s—single-movement orchestral pieces that drew inspiration from, or were somehow linked to, literary or other extra-musical sources. The concept proved popular and the repertoire quickly expanded thanks to impressive contributions by such composers as Smetana, Saint-Saëns, Franck, and, most impressively of all, Richard Strauss, who carried the precepts of Romanticism through to the middle of the 20th century, stubbornly and gloriously.

Symphonic poems (or “tone poems”) stood at the crux of the aesthetic conflict between absolute music and program music, a deeply partisan issue at the time. Absolutists held to the belief that compositions should be worked out according to strictly musical logic, like Brahms symphonies, while the program faction championed illustrative pieces like symphonic poems. Strauss fell under the spell of the latter, and from the late 1880s on he produced nine symphonic poems. He recalled in his memoirs that he was drawn to the concept that “new ideas must search for new forms; this basic principle of Liszt’s symphonic works, in which the poetic idea was really the formative element, became henceforward the guiding principle for my own symphonic work.”

The Story and Music

Don Juan was an early entry among Strauss’s tone poems, composed in 1888-89 and premiered the latter year in Weimar, where Liszt had formerly reigned supreme. The extramusical impetus for this work was the infamous womanizer of legend, whose libertine exploits were apparently born in popular literature of the 16th century and then elaborated through generations of poets, playwrights, and novelists. Strauss based his piece on a versified version of the tale by Nikolaus Lenau, an Austro-Hungarian poet born in what is now Romania. Lenau wrote it in 1844, not completing it before he was institutionalized for his six remaining years following a mental breakdown. His friend and biographer Ludwig August von Frankl attributed this observation to the poet: “My Don Juan is no hot-blooded man eternally pursuing women. It is the longing in him to find a woman who is to him incarnate womanhood, and to enjoy in the one, all the women on earth, whom he cannot as individuals possess.”

And yet he does pursue them. He woos them—and possibly goes beyond mere wooing, if we take Strauss’s tone poem as testimony, since it includes two episodes of passionate love music involving different women. Don Juan is portrayed as heroic—a real swashbuckler at the piece’s opening, where the strings suggest his leaping into action, then later when a quartet of horns emphasizes his noble bearing, fortissimo and in unison. The musical storytelling is carried out with clarity: seductions and interruptions, a masked ball, his inevitable death. At the end, a violent crash in the orchestra represents the thrust of a sword being run through him by a young aristocrat avenging his father, who was murdered by the Don. His life slips away via a discordant note from the trumpets and the piece evaporates in its final tableau.

Program music aficionados found much to admire in this work, but even the absolute music faction might have taken consolation in that fact that Strauss plots his work in a way that makes musical sense of a rather conventional sort; the entire tone poem is laid out in a more-or-less traditional sonata form—exposition, development, recapitulation—and in that sense it would stand on its own even without its underlying plot.

—James M. Keller

Read a reminiscence from James M. Keller.

Symphony No. 7 in C major, Opus 105

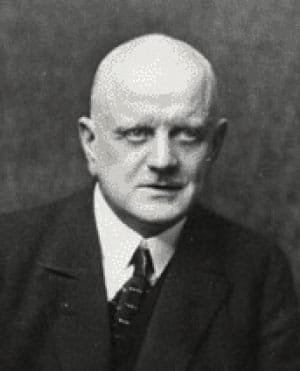

Jean Sibelius

Born: December 8, 1865, in Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died: September 20, 1957, in Järvenpää, Finland

Work Composed: 1924

San Francisco Symphony Performances: First—January 1941. Thomas Beecham conducted. Most recent—June 2018. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

Jean Sibelius’s Seventh Symphony begins with a soft triple rap on a drum. It is a summons to which the strings respond with a scale that rises mysteriously from the depths of the orchestra. The scale arrives on a chord that is strange both in sonority and harmonic implication. The quiet matter-of-factness of the triple drum beat, the nature of the response and its quickness, the range of conversational possibilities suggested—all these features make this seem not like the beginning of a discourse but like the resumption of one long in progress and but briefly interrupted. So in a sense it is. Sibelius is one of those artists whose life work is of a piece, whose major statements are in conversation with one another, extending, confirming, contradicting, but always continuing.

Plans for the last three symphonies grew simultaneously. And as early as May of 1918 Sibelius wrote this description: “The Seventh Symphony. Joy of life and vitalité with appassionata passages. In three movements—the last a ‘Hellenic Rondo.’” Very little of what Sibelius imagined about the Seventh Symphony in 1918 was realized in the score he completed six years later. The Seventh is intensely, frighteningly appassionata music, though not in any sense wild. Its amazing close does not grow out of a “Hellenic Rondo”; it is, rather, a musical gesture that should leave a witness bereft of speech and to which one responds with concert-hall applause only in order not to explode.

The Music

The Seventh did not, as Sibelius had projected, turn out to be in three movements; rather, it is a single movement. Almost up to the day of the first performance the composer called it Fantasia sinfonica. Within its span, tempo and character change often. The sequence reads this way (with boldface and line breaks added to show grouping around the most prominent sections):

Adagio–

Vivacissimo–Adagio–Allegro molto moderato–

Allegro moderato–Vivace–Presto–

Adagio–Largamente molto–Affettuoso–Tempo I

These changes are not of equal weight, and we do not hear all of them as structural or expressive markers. The Allegro molto moderato, for example, is only a brief transitional upbeat to the Allegro moderato, which is a “real” tempo (if you like, a real movement). Vivace and Presto are simply successive intensifications of that Allegro moderato. Similarly, Largamente molto and Affettuoso are intensifications of the Adagio, and the final Tempo I is only four measures long.

The twice-recurring Adagio is the same music. This suggests that after all something does remain of Sibelius’s original three-movement plan. Or, elaborating a bit, we can say Sibelius gives us an Adagio, which is the symphony’s single biggest section; a scherzo-like Vivacissimo; a sonata-like Allegro moderato, reached by way of a brief reappearance of the Adagio; and a spacious and weighty coda, which actually begins with a brief (and immediately decelerating) Presto, but most of which consists of a final return to the Adagio.

What makes this arresting and powerful is how Sibelius has made these three movements plus coda into a single piece. Robert Layton has written: “The Seventh consummates the 19th-century search for symphonic unity.” That search for a formal principle which enables a composer to write one movement that is at the same time several movements—or, if you prefer, several movements that function as the parts of a single movement—is usually reckoned to have begun with Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy. Liszt was one of the bold explorers, and the symphonic poems of Richard Strauss are in this tradition.

In the Seventh Symphony, changing tempos are not merely a condition of Sibelius’s task; his control of speed is the key to his awesome mastery of transition both on the grandest as well as on the minutest scale. To quote a fancifully evocative paragraph by Donald Tovey:

If [the listener] cannot tell when or where the tempo changes, that is because Sibelius has achieved the power of moving like aircraft, with the wind or against it. . . . [He] moves in the air and can change his pace without breaking his movement. The tempi in his Seventh Symphony range from a genuine adagio to a genuine prestissimo. Time really moves slowly in the adagio, and the prestissimo arouses the listener’s feeling of muscular movement instead of remaining a slow affair written in the notation of a quick one. But nobody can tell how or when the pace, whether muscular or vehicular, has changed.

Though several conductors claimed to have had an Eighth Symphony promised to them, the Seventh was Sibelius’s last. After 1926, Sibelius, who lived until 1957, wrote no major composition that survives. Perhaps he felt that, while he had left room for that darkly elusive postscript, the great tone poem Tapiola, he could not add another symphony. He was, almost incomparably, a master of final cadences, the handsomely satisfying ones and the deeply disturbing, and in that crunch of instruments converging on a chord of C major in his Seventh Symphony he had said, and has said beyond recall, The End.

—Michael Steinberg

This program note has been edited for length.

Rewilding

Gabriella Smith

Born: December 26, 1991, in Berkeley, California

Work Composed: 2025

SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (doubling piccolos), 3 oboes, 3 clarinets (1st and 2nd doubling clarinet in E-flat and 3rd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion (used bicycles, walnuts, mixing bowls, twigs and branches, found metal objects), and strings

Duration: About 23 minutes

Gabriella Smith’s music takes us outside the concert hall and into the natural world. Through evocative soundscapes inspired directly by her own experiences in wild places, she invites listeners to join her in discovering what she calls “the joys of climate action” while connecting deeply with our planet and its inhabitants.

Growing up in Berkeley, Smith’s passions for music and nature ran parallel to one another. When she wasn’t composing, she was volunteering for local conservation projects or backpacking—the John Adams Young Composers Project and a songbird research project in Point Reyes were particularly formative. After leaving the Bay Area to attend the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, she found herself longing for her wild West Coast home and began writing more and more about nature. Over time, her music and her life outdoors have become inextricably entwined.

The grandeur and sonic inventiveness of Smith’s music lends itself naturally to the orchestra. Recently, she has had pieces performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic. Her work Tumblebird Contrails has been played throughout the world, most notably at the 2023 Nobel Prize Concert by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, and by the San Francisco Symphony that same year. Local concertgoers may also remember her organ concerto last season, Breathing Forests. Rewilding is her first San Francisco Symphony commission. In a recent interview, she talked about how meaningful it is to have the SF Symphony perform her work: “it feels incredibly special to work with the orchestra because I grew up hearing them perform.” (She will return to curate a SoundBox program in April 2026.)

Smith described what drives her most recent compositions: “We are up against this narrative driven for decades by fossil fuel companies that tells us environmentalism is only about sacrifice and individual action. Our job in the climate movement is to show people that climate action is actually about joy and community.”

The Music

Rewilding is inspired by Smith’s work in ecological restoration, specifically rewilding, an approach that turns areas transformed by humans back into functioning natural ecosystems. She writes:

Throughout my life, I’ve worked on many different rewilding projects around the world, the most recent being on a former airplane runway in Seattle. There are so many beneficial environmental results of rewilding, but the thing that keeps me coming back is pleasure: the pleasure of getting my hands in the dirt, of hearing northern flickers and Bewick’s wrens, of biking to and from the site (another climate solution that consistently brings me joy), and the pleasure of being part of something bigger.

To musically evoke the sounds of the outdoors, Smith calls for unusual uses of traditional instruments. Some of these techniques are part of the standard toolbox of extended techniques used by many contemporary composers, but some are entirely of her own invention. She also extends the orchestra’s timbral possibilities into our everyday world through playful uses of found objects. Tea strainers, chopsticks, mixing bowls—nothing is off limits as a potential musical instrument. In Rewilding, she prominently employs bicycle parts and asks for bulk foods like walnuts to be swirled in metal bowls by the percussionists.

As she always does when beginning work on a new piece, Smith recorded herself improvising on the violin to build a palette of musical ideas. One of her improvisations became a track with eight different layers of recorded violin sounds. The result could easily be mistaken for a live frog chorus. It was a perfect fit for Rewilding because the sound of frogs is particularly poignant and joyful in the context of habitat restoration—a healthy amphibian population is one of the strongest signs of a thriving ecosystem.

Rewilding begins with the playful yet meditative sound of bicycle wheels, evoking Smith’s bicycle commute to and from the rewilding site. The music swells in joyful waves. We hear frantic activity in the winds, sometimes whirring, sometimes pointillistic like a chorus of insects. Frog-like sounds in the strings set the scene (she instructs the musicians to “be a frog”). As we descend from these ecstatic heights, the music gradually evaporates until we are left with nothing but the gentle clicking and singing-bowl-resonance of the bicycle wheels.

Smith writes, “Getting through the climate crisis will take everything we have—courage, persistence, dedication, hard work, but also imagination and creativity, community and love.” Rewilding envelopes us in this vision.

—Allegra Chapman

Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, Opus 28

Richard Strauss

Work Composed: 1895

San Francisco Symphony Performances: First—February 1914. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—January 2018.

Michael Tilson Thomas conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes, piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, 6 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and ratchet), and strings

Duration: About 16 minutes

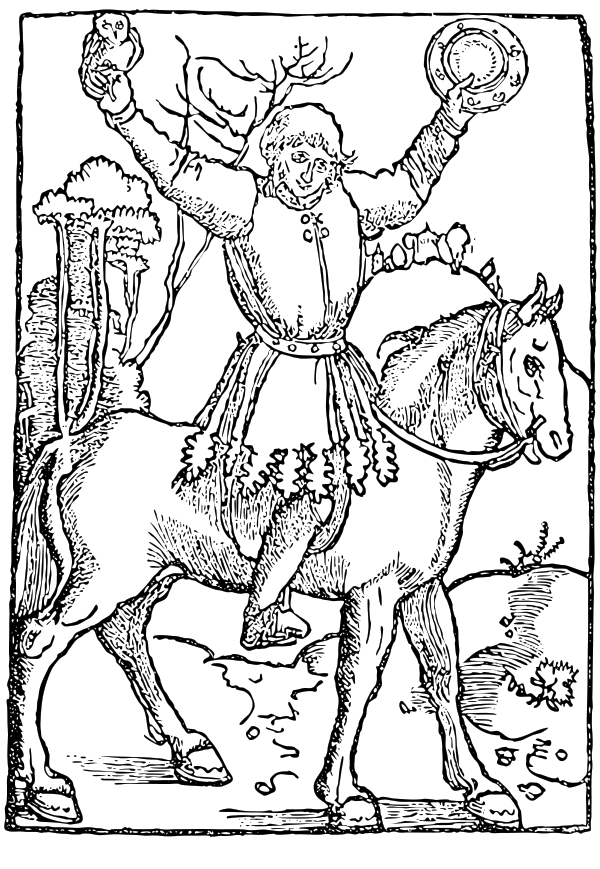

There was an actual Till Eulenspiegel, born early in the 14th century near Braunschweig and gone to his reward—in bed, not on the gallows as in Strauss’s tone poem—in 1350 at Mölln in Schleswig-Holstein. Stories about him have been in print since the beginning of the 16th century, the first English version coming out around 1560 under the title Here beginneth a merye Jest of a man that was called Howleglas (Eule in German means “owl” and Spiegel, “mirror,” or “looking-glass”). The consistent and serious theme behind his jokes and pranks, often in themselves distinctly coarse and even brutal, is that of an individual getting back at society, specifically, the shrewd peasant more than holding his own against a stuffy bourgeoisie and a repressive clergy. The most famous version of Till Eulenspiegel is the one published in 1866 by the Belgian novelist Charles de Coster.

Richard Strauss knew de Coster’s book, and it seems also that in 1899 in Würzburg he saw an opera called Eulenspiegel by Cyrill Kistler, a Bavarian composer whose earlier opera Kunihild had a certain currency in the 1880s and early ’90s, and for which he was proclaimed Wagner’s heir. Strauss’s first idea was to compose an Eulenspiegel opera. He sketched a scenario and later commissioned another, but somehow the project never got into gear. “I have already put together a very pretty scenario,” he wrote in a letter, “but the figure of Master Till does not quite appear before my eyes.”

But if Strauss could not see Master Till, he could hear him, and before 1894 was out, he had begun the tone poem that he finished the following May. As always, he could not make up his mind whether he was engaged in tone painting or “just music.” To Franz Wüllner, who conducted the first performance, he wrote:

I really cannot provide a program for Eulenspiegel. Any words into which I might put the thoughts that the several incidents suggested to me would hardly suffice; they might even offend. Let me leave it, therefore, to my listeners to crack the hard nut the Rogue has offered them. By way of helping them to a better understanding, it seems enough to point out the two Eulenspiegel motifs [Strauss jots down the opening of the work and the virtuosic horn theme], which, in the most diverse disguises, moods, and situations, pervade the whole up to the catastrophe when, after being condemned to death, Till is strung up on the gibbet. For the rest, let them guess at the musical joke a Rogue has offered them.

On the other hand, for Wilhelm Mauke, the most diligent of early Strauss exegetes, the composer was willing to offer a more detailed scenario—Till among the market women, Till disguised as a priest, Till paying court to pretty girls, and so forth—the sort of thing guaranteed to have the audience anxiously reading the program book instead of listening to the music and missing most of Strauss’s dazzling invention in the process. It is probably useful to identify the two Till themes, the very first violin melody and what the horn plays about 15 seconds later, and to say that the opening music is intended as a “once-upon-a-time” prologue that returns after the graphic trial and hanging as a charmingly formal epilogue with a rowdily humorous “kicker.” For the rest, Strauss’s compositional ingenuity and orchestral bravura, plus your attention and fantasy, will see to the telling of the tale.

—M.S.

About the Artist

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

Read our Salonen feature “In Good Time,” SF Symphony Musicians’ Salonen remembrances, and more: