In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, November 23, 2025, at 2:00pm

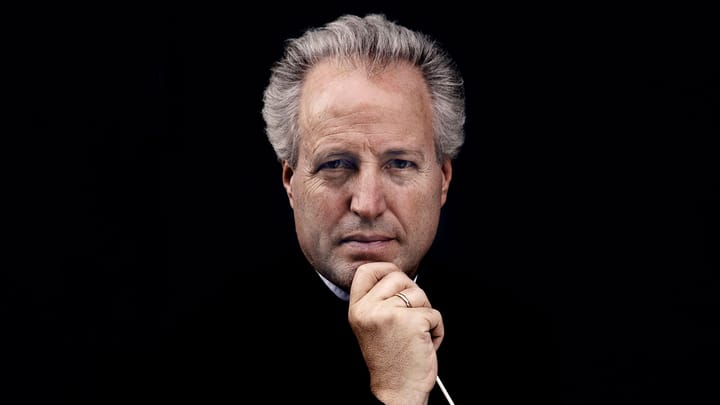

Radu Paponiu conducting

Wattis Foundation Music Director

Gabriela Ortiz

Kauyumari (2021)

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, Opus 64 (1844)

Allegro molto appassionato

Andante–

Allegretto non troppo–Allegro molto vivace

Aaron Ma

Intermission

Johannes Brahms

Academic Festival Overture, Opus 80 (1880)

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 8 in G major, Opus 88 (1889)

Allegro con brio

Adagio

Allegretto grazioso

Allegro ma non troppo

Program Notes

Kauyumari

Gabriela Ortiz

Born: December 20, 1964, in Mexico City

Work Composed: 2021

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (tambourine, suspended cymbal, tam-tam, snare drum, bongo drums, log drum, bass drum, claves, metal guiro, jawbone, shaker, seed pod rattle, sistrum, glockenspiel, and xylophone), harp, and strings

Duration: About 7 minutes

Gabriela Ortiz was commissioned by Gustavo Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 2021 to write a piece to reflect on the orchestra’s return to the stage following the pandemic. Ortiz writes that she immediately thought of Kauyumari, a mythical blue deer that serves as a spirit guide for the Huichol people of Nayarit and Jalisco, Mexico. Each year, Huichols embark on a spiritual pilgrimage, guided by the hallucinogenic cactus peyote. They hunt Kauyumari and make offerings to show gratitude for finding their way to the spiritual world.

Ortiz’s inspiration for Kauyumari came from an album by the De La Cruz family of Huichol singers. In Huichol music, a melody can be repeated hundreds of times. Ortiz likens this to a mantra or a ritual. Her piece, too, repeats itself over and over again, but each repetition has a slightly different accompaniment, orchestration, register, and character.

The piece opens with two muted offstage trumpets playing a quiet murmur of the melody. Grace notes in the piccolo lend a folk vocality to the melody when it takes over from the trumpets. Each iteration has a slightly different set of grace notes and melody which makes it sound more improvisatory and exciting. The accompaniment in the final few minutes of the piece is almost all continuous eighth notes, building in intensity and motion. The melody eventually speeds up over the course of the piece, building to a vibrant climax.

There were few more joyful moments than returning to work to play music with friends and colleagues after the pandemic lockdown. Ortiz notes that she wants Kauyumari to be fun for the musicians to play. It is exactly that: an unending groove that reminds us of why we love to play music together. The ineffable joy of being around other musicians who are all working together to create something magical is the spiritual journey. Peyote or not, this piece puts listener and musician alike in a ritualistic trance, together.

Violin Concerto in E minor, Opus 64

Felix Mendelssohn

Born: February 3, 1809, in Hamburg

Died: November 4, 1847, in Leipzig

Work Composed: 1838–44

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 27 minutes

Felix Mendelssohn’s love of classical forms, his desire to write a serious piece of music for the violin, and his consideration for his place in the canon all helped lead him to compose his violin concerto. This contrasted with the “showpiece concertos” by composer-performers such as Niccolò Paganini, who were more concerned with virtuosic pyrotechnics. In addition, Mendelssohn’s friend and colleague Ferdinand David was an important inspiration for the work. David was one of the most important violinists of his time: he was a soloist, the leader of his string quartet, and the concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, where Mendelssohn was music director. He was also a teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory, which Mendelssohn founded in 1843. Mendelssohn and David collaborated on the concerto, and it is likely that David helped with the writing of the cadenza.

Mendelssohn’s violin concerto is innovative in several ways. First, audiences at this time would not always sit in rapt attention. Therefore, Mendelssohn eschews a long, drawn-out orchestral introduction in favor of only a bar and a half of a static E-minor chord. The audience would have sat straight up in their seats to listen to the soloist play in their high register, soaring out over the low-lying strings and winds. Mendelssohn utilizes the full range of the instrument, from the lowest G to the highest reaches of the instrument.

Another interesting innovation in the concerto is that it is through-composed. In other words, Mendelssohn does not stop between the movements, but composes straight from one movement into the next. This was likely to prevent the audience from applauding between the movements and to keep their attention from wandering. He ensured that the premiere with his home orchestra at the Leipzig Gewandhaus would have proceeded the way he wanted it to. Finally, Mendelssohn wrote out the concerto’s cadenza, likely with the help of David, who was the soloist at the premiere. Usually, composers would allow the soloist to improvise the cadenza, but it is likely that Mendelssohn was hoping to avoid seeing someone showboat the cadenza in a way that did not align with his own compositional sensibilities.

Academic Festival Overture, Opus 80

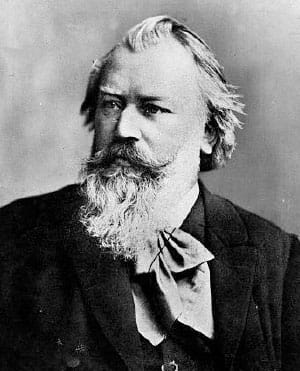

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1880

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 10 minutes

Johannes Brahms’s Academic Festival Overture was written as a musical thank-you note to the University of Breslau (today, Wrocław, Poland) for granting him an honorary doctorate. He had wanted to write a regular thank-you note, but the director of music there, Bernard Scholz, intimated that they expected some sort of musical recompense. So, Brahms obliged. The “academic” elements of the music here can be found in student songs (usually sung while enjoying beverages together) placed throughout the work. It could be said that the emphasis of this piece should be placed more on the word “festival” than “academic.”

There are several popular tunes quoted throughout the overture. The opening is based on the Rákóczi March, a Hungarian piece that Brahms had loved since he was a child. It is also found in Berlioz’s Hungarian March from The Damnation of Faust. Later, three trumpets play the chorale, “Wir hatten gebauet ein stattliches Haus” (we have built a stately house). This Thuringian folk song was turned into a student protest song, and any student would have recognized it. Then the Rákóczi melody returns, albeit slightly differently. After that is “Der Landesvater,” (The father of our country), a lyrical, beautiful melody from the violins and the violas.

Not all of the music is serious, of course. Soon, the bassoons play the rollicking tune from “Was komm dort von der Höh” (What comes from afar). Brahms has a little fun, bringing out the silly character only a bassoon can evoke. At the end, “Gaudeamus igitur” (Therefore, let us be merry) resounds throughout the orchestra, making a joyful noise to conclude the piece.

Symphony No. 8 in G major, Opus 88

Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died: May 1, 1904, in Prague

Work Composed: 1889

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

Antonín Dvořák composed his Eighth Symphony in under one month during the summer of 1889. Thirty-five minutes of music composed over the course of a month may not seem extraordinary until one considers that Dvořák had to write 14 lines of music out all by hand, then edit and correct it. He found deep inspiration from his summer home in Vysoká, and in the Czech and Slavonic folk music he heard around him. The composer wanted to develop a new musical language that felt truly like him, not the music that was expected of him.

Importantly, Dvořák didn’t want to have to write the music that his publisher, Simrock, demanded. Simrock, one of the most famous music publishers of the time, pushed Dvořák to publish shorter, easier-to-sell works for piano and chamber groups. Dvořák refused and instead wrote a symphony that was influenced by pastoral sounds, fanfares (as in the opening of the finale), a quasi-funeral march, and folk music. When the composer submitted the manuscript for publication, the publisher offered him half of what he was expecting. In contrast, Johannes Brahms had been paid five times as much for his recent symphony. Rather than accept this low offer, Dvořák published the symphony with an English publishing house, Novello.

While this may seem a small detail, it illustrates how Dvořák felt his music was not appreciated the way it should have been because of the hierarchy of Austro-Germanic composers. Thankfully, Dvořák is now one of the most famous symphonists within the canon. And for good reason; this symphony pushes the boundaries of forms and expectations in favor of a more rhapsodic, naturalistic work. Dvořák develops motives and melodies with free expression, rather than focus mainly on following forms.

The Music

The first movement of the symphony opens with a beautiful, somber melody in the cellos, clarinets, bassoons, and horns. Interestingly, this melody was actually written after the rest of the symphony was completed. Dvořák finds ways to reintroduce this theme later in the movement but it shows how this symphony is guided by feel rather than by form.

Many symphonic works during the 19th century were inspired by Beethoven’s symphonic works. His symphonies represented the pinnacle of achievement against which all other subsequent symphonies were to be judged. Unsurprisingly, the second movement bears a striking resemblance to the slow movement of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, with its motivic triplets, moving from C minor to C major, and back again. Dvořák, however, stays in major at the end of the movement, signifying perhaps a more hopeful outlook than his predecessor.

The third movement is a beautiful scherzo movement with a melancholic waltz. Finally, the trumpets herald the arrival of the fourth movement, a theme and variations. After almost lulling itself to sleep with a trick ending, Dvořák shakes the orchestra awake with a jolt and they race toward the finish line.

—Alicia Mastromonaco

About the Artists

Radu Paponiu

Radu Paponiu was appointed Wattis Foundation Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra in fall 2024. Before that, he completed a five-year tenure as associate conductor of the Naples Philharmonic and a seven-year tenure as music director of the Naples Philharmonic Youth Orchestra. He has also served as music director of the Southwest Florida Symphony, assistant conductor of the Naples Philharmonic, and as a member of the conducting faculty of the Juilliard Pre-College.

As a guest conductor, Paponiu has appeared with the Romanian National Radio Symphony, Teatro Comunale di Bologna Orchestra, Transylvania State Philharmonic, Banatul Philharmonic, Louisiana Philharmonic, Rockford Symphony, Colorado Music Festival Orchestra, North Carolina Symphony, California Young Artists Symphony, and National Repertory Orchestra. He has collaborated with soloists such as Evgeny Kissin, Yefim Bronfman, Emanuel Ax, Gil Shaham, Midori, Vladimir Feltsman, Robert Levin, Charles Yang, Nancy Zhou, Stella Chen, and the Ébène Quartet.

Born in Romania, Paponiu began his musical studies on the violin at age seven, came to the United States at the invitation of the Perlman Music Program, and later completed two degrees in violin performance at the Colburn School. He went on to earn a master's degree in orchestral conducting at New England Conservatory, where he studied with Hugh Wolff.

Aaron Ma

Aaron Ma began his musical journey at the age of three under the guidance of his mother, pianist Hang Li. He started learning violin at five with Zhao Wei, with whom he continues to study at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music Pre-College. From 2019 to 2022, he studied piano with William Wellborn at SFCM. Additionally, Ma works with Ian Swensen and is coached by David Chernyavsky from the San Francisco Symphony. He has been a member of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra since 2022 and joined Young Chamber Musicians in the 2024–25 season. He is currently a junior at the Harker School.

Ma has received top prizes from various competitions. In addition to winning the 2024–25 SFSYO Concerto Competition, he was the first prize winner of the 2023 Pacific Musical Society & Foundation Annual Competition. Ma has played for distinguished musicians including Alexander Barantschik, Nancy Zhou, Stella Chen, Soovin Kim, Simon James, and Arnaud Sussman. He has been coached in chamber music by the Alexander String Quartet, Telegraph Quartet, Calidore String Quartet, Ying Quartets, and Trio Karenine.

In the summer of 2025, Ma was invited to the Young Artist Institute of Chamber Music Northwest, and he toured East Asia with the National Youth Orchestra of the USA. During the summer of 2024, at the Meadowmount School of Music, Ma studied under Gerardo Ribeiro from Northwestern University. In the summer of 2023, he participated in Music@Menlo and the Bowdoin International Music Festival.

San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra

The San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra is recognized internationally as one of the finest youth orchestras in the world. Founded by the San Francisco Symphony in 1981, the SFSYO’s musicians are chosen from more than 200 applicants in annual auditions. The SFSYO’s purpose is to provide an orchestral experience of preprofessional caliber, tuition-free, to talented young musicians. The more than 100 musicians, ranging in age from 12 to 21, represent communities from throughout the Bay Area. The SFSYO rehearses and performs at Davies Symphony Hall under the direction of Radu Paponiu, who joined the San Francisco Symphony as Wattis Foundation Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra in the 2024–25 season. Jahja Ling served as the SFSYO’s first Music Director, followed by David Milnes, Leif Bjaland, Alasdair Neale, Edwin Outwater, Benjamin Shwartz, Donato Cabrera, Christian Reif, and Daniel Stewart.

As part of the SFSYO’s innovative training program, musi-cians from the San Francisco Symphony coach the young play-ers each Saturday afternoon in sectional rehearsals, followed by full orchestra rehearsals with Radu Paponiu. Youth Orchestra members regularly meet and work with world-renowned artists: Esa-Pekka Salonen, Michael Tilson Thomas, Herbert Blomstedt, Kurt Masur, John Adams, Yo-Yo Ma, Valery Gergiev, Isaac Stern, Yehudi Menuhin, Wynton Marsalis, Midori, Joshua Bell, Mstislav Rostropovich, Simon Rattle, and many others have worked with the Youth Orchestra. Of equal importance, Youth Orchestra members are able to speak with these prominent musicians about their professional and personal experiences, and about music. The ensemble has toured Europe and Asia, given sold-out concerts in such legendary halls as Berlin’s Philharmonie, Vienna’s Musikverein, Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater, and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, and won first prize in Vienna’s International Youth and Music Festival.

San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra

First Violins

Euisun Hong, Co-Concertmaster

Lawrence V. Metcalf Chair

Andrew Zhang, Co-Concertmaster

Lawrence V. Metcalf Chair

Ethan Chang

Christina Hong

Hyesun Hong

Maximilian Huang

Kayla Hwang

Constance Kuan

Aaron Ma

Magdalena Masur

Henry Miller

Carolyn Ren

Yujin Shin

Calliope Smith

Jenna Son

Henry Stroud

Kate Vo

Lucas Wang

Lucy Wang

Second Violins

Asher Cupp, Co-Principal

Lisa Saito, Co-Principal

Léopoldine Bréard

Maggie Cai

Janet Chan

Dylan Chua

Udo Funke

Brandon Gao

Evelyn Holmes

Katherine Jang

Sarah Kumayama

William Liang

Veronica Qiu

Serena She

Oliver Spivey

Braden Wang

Yihe Wang

Junnosuke Yanagisawa

Katherine Yoo

Riona Zhu

Violas

Bryan Im, Co-Principal

Yufei Shen, Co-Principal

Rebekah Sung, Co-Principal

Harper Berry

Colin Breshears

Jamie Cheung

Timothy Cheung

Olivia Haddick

Jaydon Li

Haoching Liu

Olivia Park

Galen Russell

Rohan Sangani

Laurelin Stroh

Nicole Targosz

Cellos

Melissa Lam, Co-Principal

Ethan Lee, Co-Principal

Claire Topper, Co-Principal

Ya-Ching Chan

Timothy Huang

Anthony Jung

Donghu Kim

Blanche Li

Lukas Masur

Yoonsa Park

Cara Wang

Double Bass

Rouyan Lechner, Co-Principal

Allison Prakalapakorn, Co-Principal

Alec Blair

Haku Homma

Hani Khayatei Houssaini

Vera Kolodko

Yoav Konig

Rudie Sheehy

Raiden Tan

Eric Zhang

Flutes

Diego Fernandez

Esther Kim

Wanruo Zhang

Oboes

Gabriel Chodos

Jesse Spain

Liam Ta

Asher Wong

Clarinets

Ryan Beiter

Subin Kim

Hanting Liu

Adam Thyr

Bassoons

Matthew Chan

Adam Erlebacher

Stuthi Jaladanki

Aya Watanabe

Horns

Daniel Cooper

Elinor Cooper

Owen Ellis

Violet MacAvoy

Owen Sheridan

Trumpets

James Lee

Julian Moran

Brady Phan

Ivan Sokolenko

Trombones

Harvy Chang

Ethan Moran

Tuba

Cameron Strahs

Percussion & Timpani

Garrett Guo

Jeffrey Lee

Derick Shu

Alexander Xie

Aeneas Yu

Harps

Jessica Cheung

Camille Chu

Keyboard

Dylan Hall

Radu Paponiu,

Wattis Foundation Music Director

Coaching Faculty

David Chernyavsky, Violin

In Sun Jang, Violin

Chen Zhao, Violin

Adam Smyla, Viola

Jill Brindel, Cello

David Goldblatt, Cello

Stephen Tramontozzi, Bass

Catherine Payne, Flute

Russ de Luna, Oboe

Brooks Fisher, Oboe

Matthew Griffith, Clarinet

Jerome Simas, Clarinet

Justin Cummings, Bassoon

Jack Bryant, Horn

Jeff Biancalana, Trumpet

Jonathan Seiberlich, Trombone & Tuba

Jacob Nissly, Percussion & Timpani

Marty Thenell, Percussion & Timpani

Katherine Siochi, Harp

Marc Shapiro, Keyboard

Youth Orchestra Administration

Daniel Hallett, Associate Director,

Youth Orchestra Program

Katie Lee, Youth Orchestra

Administrative Apprentice

Hung-Yu Lin, Youth Orchestra

Administrative Apprentice

Charlotte Lopez, Youth Orchestra

Library Apprentice

Lily Wang, Youth Orchestra

Library Apprentice