In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, May 15, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, May 16, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, May 17, 2025, at 7:30pm

Preconcert talk by Principal Timpani Edward Stephan: on stage at 6:30pm

Dalia Stasevska conducting

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis (1910)

Anna Thorvaldsdottir

Before we fall (2024)

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Johannes Moser cello

Intermission

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Opus 82 (1915)

Tempo molto moderato–Allegro moderato–Presto

Andante mosso, quasi allegretto

Allegro molto–Misterioso

Dalia Stasevska’s appearance is supported by the Louise M. Davies Guest Conductor Fund.

The San Francisco Symphony premiere of Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s Before we fall for Johannes Moser is made possible by a generous gift from Elizabeth and Justus Schlichting.

These concerts are supported in part by the Mr. and Mrs. George J. Otto Sibelius Fund, the Barbara Brookins Young Artist Fund, and the Joan L. Danforth Guest Artist Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

This is followed by the world premiere of Icelandic composer Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s Before we fall, a cello concerto and San Francisco Symphony commission performed by the German-Canadian soloist Johannes Moser. Thorvaldsdottir grew up studying cello herself, giving her firsthand insight into how its rich tenor voice could be worked into her elemental, boundary-blurring music.

On the second half is Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 5, written after a successful tour of America but also at the start of the First World War. He jotted in his notebook: “In a deep valley again. But I already begin to see dimly the mountain that I shall certainly ascend. . . . God opens His door for a moment and His orchestra plays the Fifth Symphony.” Listen for the noble “Swan theme” as it emerges in the brass and moves through the strings in the finale.

Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis

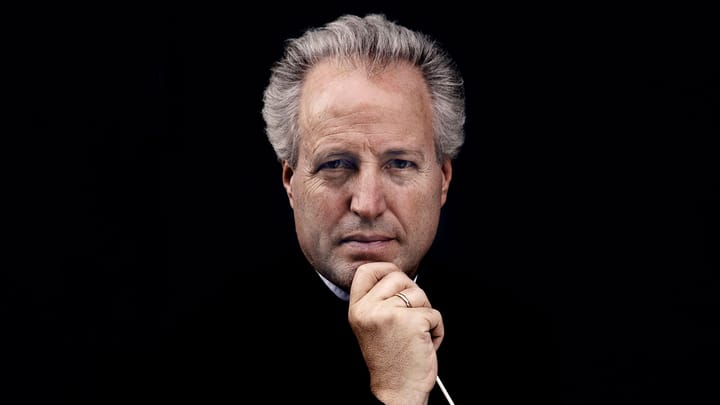

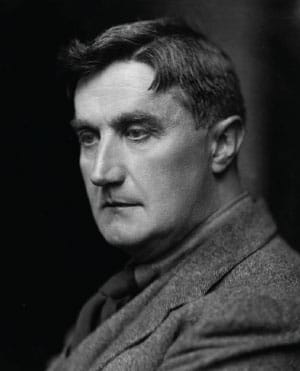

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: October 12, 1872, in Down Ampney, England

Died: August 26, 1958, London

Work Composed: 1910

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1939.

Pierre Monteux conducted. Most Recent—December 2006.

Yan Pascal Tortelier conducted.

Instrumentation: strings

Duration: About 15 minutes

A vicar’s son turned cheerful agnostic, Ralph Vaughan Williams retained a deep appreciation for sacred music. He knew that music was a form of worship, a glimpse of transcendence available to believers and skeptics alike. In 1904 he agreed to edit The English Hymnal, and he dedicated the better part of two years to the project, immersing himself in the obscure musical forms of the distant past. He did more than compile: He adapted folk-song arrangements and even composed new music when necessary. But the time he devoted to the hymnal wasn’t a sacrifice; it was an investment in his art. “I wondered if I was wasting my time,” the composer later wrote, “but I know now that two years of close association with some of the best (as well as some of the worst) tunes in the world was a better musical education than any amount of sonatas and fugues.”

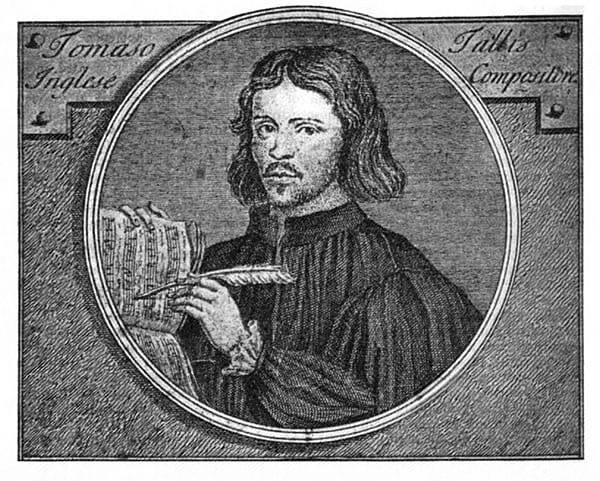

Four years after his revisions to the Hymnal were finished, Vaughan Williams composed his Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. Tallis (ca. 1505–85), whose music figured prominently in the collection, served four English monarchs, starting with Henry VIII and ending with Elizabeth I. The theme Vaughan Williams chose for the Fantasia derives from the music Tallis set to the following phrase from Psalm 2: “Why fum’th in fight the Gentiles spite, in fury raging stout.”

The Music

Completed in 1910, when Vaughan Williams was 38 years old, the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis was his first decisive masterpiece. At once intimate and otherworldly, its trembling reverence approaches the ecstatic. This is 16th-century vocal polyphony by way of a 20th-century double string orchestra: destabilizing on numerous levels. You’ll notice that the strings are divided into three parts of different sizes: a large orchestra, a smaller one, and a quartet. The Fantasia sounds lushly orchestrated despite the absence of winds, brass, and percussion. One striking effect is the halo created by the second, smaller orchestra, which mimics the acoustical reverberation of a vaulted cathedral.

To listen closely is to come unstuck in time. Glimmering in that magical middle distance—somewhere in the ancient future—the sacred comes alive.

—René Spencer Saller

This note originally appeared in the program book of the Dallas Symphony.

Before we fall

Anna Thorvaldsdottir

Born: July 11, 1977, in Reykjavík, Iceland

SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: solo cello, 2 flutes, alto flute, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trombones, tuba, percussion (2 thunder sheets, large tam-tams, 2 large bass drums), and strings

Duration: About 25 minutes

The sonic ecosystems in Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s music are often inspired by principles like proportion and flow, which are rooted in the natural world. In an episode of WNYC’s Meet the Composer podcast, violist Nadia Sirota described: “Anna often favors massive ensembles, writing delicate and detailed parts for every player . . . [she] summons these massive sonorities—detailed, elegant tapestries with a seductive gravity, which pull the listener in.” And according to Gramophone, Thorvaldsdottir’s music embodies a “combination of power and intimacy.”

Now based in London, Thorvaldsdottir was raised in the small Icelandic town of Borgarnes, studied at what is now the Iceland University of the Arts in Reykjavík, and went on to earn a PhD from the University of California San Diego in 2011. Since then, her music has been commissioned and performed by many of the world’s leading orchestras, ensembles, and presenters, including the Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Gothenburg Symphony, Munich Philharmonic, International Contemporary Ensemble, Ensemble Intercontemporain, Danish String Quartet, BBC Proms, and Carnegie Hall. Her most recent orchestral works include ARCHORA, premiered in 2022 at the BBC Proms, and CATAMORPHOSIS, premiered in 2021 by the Berlin Philharmonic. This season she is the Tonhalle Orchestra’s creative chair, and was composer in residence with the Iceland Symphony from 2018 through 2023. The San Francisco Symphony and Esa-Pekka Salonen performed her METACOSMOS in January 2019, and two of her works also appeared on a 2018 SoundBox program curated by Christian Reif.

Portrait concerts with Thorvaldsdottir’s music have been featured at Wigmore Hall, the Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music, Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival, Miller Theatre at Columbia University, the Phillips Collection, Knoxville’s Big Ears Festival, and Brooklyn’s National Sawdust. Albums of Thorvaldsdottir’s works have appeared on Deutsche Grammophon, Sono Luminus, and Innova, with Sono Luminus having released recordings of all of her orchestral works to date.

The Music

The cello concerto Before we fall was commissioned in 2022 by the San Francisco Symphony, Iceland Symphony, Helsinki Philharmonic, Odense Symphony, and BBC Proms. In her own program note, Thorvaldsdottir (a cellist herself by training) writes:

The core inspiration behind the cello concerto Before we fall centers around the notion of teetering on the edge, of balancing on the verge of a multitude of opposites. The musical structure flows between lyricism and a sense of distorted energy—two main forces that stabilize this entropic pull. Driven by the strong sense of lyricism that permeates the piece, the work also orbits a forward-moving energy that connects and balances the opposites in different ways. The stable fundament—a grounding power of sustained harmonic presence—communicates with ethereal and distorted sounds, together providing the earth for the essence of the solo cello, the structure upon which it stands and within which it moves. The cello, both alone and deeply connected to the orchestral elements in its expression, generates the atmospheric progression of the world it inhabits, yet continuously on the verge of falling outside the reality it is building for itself.

A roiling opening statement in the full orchestra gives way to the cello’s lyric and declamatory entrance, supported by the strings. Increasing atmospheric agitations in the wind and brass—by way of liminal halting breaths, rasps, and evaporating clicks—foreshadow the trajectory of the cello, switching from lyricism to growling furor low in its range, one which slowly rises in register towards the section’s conclusion.

After a pause, in Part Two, the keening solo line and chorale-like string textures are complemented by further ethereal interjections in the brass and wind. Part Three’s cadenza, after seeing the cello’s most prolonged exploration of extended techniques and “distorted sounds,” returns to highly forward-driven material, partly anticipated in Part One, now buttressed by the double basses. The final section and epilogue see the cellist return to deeply lyrical material, the epilogue summing up the journey as the cello carries on with pleading insistence, even as the fluttering horns and sustained strings fall away.

Thorvaldsdottir adds the following comment about her creative process:

As with my music generally, the inspiration is not something I am trying to describe through the music or what the music is “about,” as such. Inspiration is a way to intuitively tap into parts of the core energy, structure, atmosphere and material of the music I am writing each time. It is a fuel for the musical ideas to come into existence, a tool to approach and work with the fundamental materials, the ideas and sensations, that provide and generate the initial spark to the music—the various sources of inspiration are ultimately effective because I perceive qualities in them that I find musically captivating. I do often spend quite a bit of time finding ways to articulate some of the important elements of the musical ideas or thoughts that play certain key roles in the origin of each piece but the music itself does not emerge from a verbal place, it emerges as a stream of consciousness that flows, is felt, sensed, shaped and then crafted. So inspiration is a part of the origin story of a piece, but in the end the music stands on its own.

—Lev Mamuya

Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Opus 82

Jean Sibelius

Born: December 8, 1865, in Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died: September 20, 1957, in Järvenpää, Finland

Work Composed: 1915 (rev. 1916, 1919)

SF Symphony Performances: First—December 1940.

Pierre Monteux conducted. Most Recent—June 2022.

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

On the evening of his 50th birthday, an event celebrated in Finland as a national holiday, Jean Sibelius led the Helsingfors Municipal Orchestra in a program of his own music—the two Serenades for violin, the symphonic poem called The Oceanides that he had written for his visit to the United States the year before, and the new and eagerly anticipated Fifth Symphony. His position as a cultural hero at home had been established 24 years earlier, with the performance of Kullervo, a massive work for voices and orchestra based on the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic. The success of his Second Symphony, first heard in 1902, had given him a name abroad. He had been granted a government pension designated to keep him in Finland and that allowed him to concentrate wholly on composition. Until Paavo Nurmi made his debut at the Antwerp Olympic Games in 1920, Sibelius was the only Finn whose name was familiar throughout the world, and his compatriots were fiercely proud of him.

Sibelius’s visit to America, where the festivities included the conferral of an honorary doctorate at Yale, was the zenith of international recognition for him. Coming home, he heard in mid-Atlantic the news of the assassination at Sarajevo of the heir to the Austrian throne. He had scarcely settled into his life again when, to his horror and disbelief, virtually all Europe was at war. “I have always hated all empty talk on political questions, all amateurish politicizing,” he had written some years earlier. “I have tried to make my contribution another way.” And now Sibelius concentrated on the new symphony he had promised to deliver in time for his birthday celebrations.

Most of his music was with a German publisher, which meant that he was cut off from his royalties for the duration of the war. Trying to deal with the resulting financial hardship, he produced some potboilers for the Danish house of Hansen; moreover, he had commitments to conduct in Sweden and Norway. With professional and public distractions, work was not easy, but the score was completed. He revised it twice before he was satisfied, pulling the original four movements into three, striving ever for concentration. Not until the spring of 1919 did political stability return to Finland, and it was only in the fall of that year that the Fifth Symphony attained its final and present form.

At the end of September 1914, Sibelius had jotted these words in his notebook: “In a deep valley again. But I already begin to see dimly the mountain that I shall certainly ascend. . . . God opens His door for a moment and His orchestra plays the Fifth Symphony.” God’s orchestra begins with an E-flat major chord so idiosyncratically voiced and scored that it says “Sibelius Five” as unmistakably as certain other E-flat chords say Emperor Concerto or Eroica Symphony. This one is built of a soft timpani roll, and the sound of French horns. Two more horns add their voices, and one of them detaches itself to play a softly musing call. This, in turn, elicits a three-note echo in flutes and oboes. Sibelius offers a few more ideas—a slowly whirling figure played by various woodwind couples, leading directly into a slower phrase for flute and clarinet; an exclamation, also with woodwinds; a sequence of chords in crescendo, cutting across the prevailing meter in cross-rhythm; and yet another exclamation.

This gives Sibelius plenty with which to generate a movement whose originality is as remarkable as its clarity. First, he lets us hear all this music again, but with the harmonic perspective realigned. That is, the first “exposition,” like its counterpart in every classical symphony, modulates to a new key; the repeat, however, stays in the original key. Now Sibelius transforms the material with wonderful diversity. Donald Tovey has described the first phase: The flute and clarinet phrase “is worked up into a wonderful mysterious kind of fugue which quickens . . . into a cloudy chromatic trembling, through which its original figure moans in the clarinet and bassoon.” In the second phase, the exclamation makes its presence known again, at a broader tempo than before and with new passion. Suddenly the tempo quickens, and the first theme is made part of a dance tune. This is in effect the symphony’s scherzo, accelerating as it unfolds. The trumpet begins a trio for this scherzo, whose recapitulation then serves as recapitulation for the entire movement. The last, obsessively repeated chord that whirls the orchestra into dizziness consists of the four notes of the horn call that emerged as the symphony’s first thematic idea.

What Sibelius does in the second movement is best described as variations on a rhythm, the thematic rhythm being nothing more complicated than two groups of five even quarter notes separated by a quarter rest. Six different tunes occur, all variants of this twice-five-note rhythm. Before the five-note figures begin, we hear some sustained introductory woodwind chords. More than preparing the appearance of the theme, they are a constant presence here, and we feel the contrast—which becomes tension—between their leisure and the gentle but persistent energy of the thematic rhythm. Twice, the variations are supported by a broadly swinging bass. Of this we shall hear more.

The finale begins in a tremendous whir. When the agitation subsides, the two pairs of French horns set up a kind of antiphonal tolling that is, in fact, the swinging bass from the previous movement. Much-divided strings accompany, playing the same music slightly out of phase. Woodwinds and cellos turn the horn theme itself into an accompaniment by superimposing a new melody of their own. Sibelius traverses this territory once more, with new harmonic perspectives revealed. The thicket of dissonance becomes ferocious and is resolved by an imperious command for silence. Then four chords and two unisons enforce order. Their sound and their timing can never cease to stun.

—Michael Steinberg

About the Artists

Dalia Stasevska

Dalia Stasevska is chief conductor of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra, artistic director of the International Sibelius Festival, and principal guest conductor of the BBC Symphony. This season, she guest conducts the Orchestre de Paris, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Oslo Philharmonic, Dresden Philharmonic, Swedish Radio Symphony, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Helsinki Philharmonic, and Finnish Radio Symphony. In North America, she returns to the Philadelphia Orchestra and Montreal Symphony, and debuts with the New World Symphony. Recent engagements have included the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and Glyndebourne Opera. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in April 2023.

Last summer, she released her debut feature album, Dalia’s Mixtape, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, featuring genre-bending composers such as Anna Meredith, Caroline Shaw, Andrea Tarrodi, Noriko Koide, Judith Weir, and Julius Eastman. With the Lahti Symphony, she also released two albums on BIS.

Stasevska studied violin and composition at the Tampere Conservatory and went on to study violin, viola, and conducting at the Sibelius Academy. In December 2018, she conducted the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic at the Nobel Prize Ceremony. In 2023, she was named one of The New York Times “Breakout Stars” and received BBC Music Magazine’s Personality of the Year Award. She was previously awarded the Alfred Kordelin Prize and the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Conductor Award. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy named her to the Order of Princess Olga, Third Class, and since 2022, she has actively supported Ukraine by raising donations and delivering supplies.

Johannes Moser

German-Canadian cellist Johannes Moser has performed with the Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic at the Proms, London Symphony, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, and Tokyo NHK Symphony. His recordings have earned the Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik and the Diapason d’Or.

Renowned for his efforts to expand the reach of the classical genre, as well as his passionate focus on new music, Moser has commissioned works from Julia Wolfe, Ellen Reid, Thomas Agerfeld Olesen, Johannes Kalitzke, Jelena Firsowa, and Andrew Norman. In 2011 he premiered Enrico Chapela’s Magnetar for electric cello with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and brought it on tour with Gustavo Dudamel and the LA Phil at Davies Symphony Hall. Throughout his career, Moser has been committed to reaching out to all audiences, from kindergarten to college and beyond.

Born into a musical family in 1979, Moser began studying the cello at the age of eight. He was the top prize winner at the 2002 Tchaikovsky Competition, in addition to being awarded the Special Prize for his interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. In 2014 he was awarded the prestigious Brahms Prize. Moser plays on an Andrea Guarneri Cello from 1694 from a private collection, and holds a professorship at the Cologne Hochschule für Musik und Tanz. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in January 2019.

Learn more about Johannes Moser in our feature “James Moser’s Playbook.”