In This Program

The Concert

Friday, October 24, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, October 25, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, October 26, 2025, at 2:00pm

Preconcert Talk with Alicia Mastromonaco

On stage Friday and Saturday at 6:30pm, Sunday at 1:00pm

David Afkham conducting

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 35 (1878)

Allegro moderato–Moderato assai

Canzonetta: Andante

Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

Sergey Khachatryan

Intermission

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Opus 65 (1943)

Adagio–Allegro non troppo

Allegretto

Allegro non troppo

Largo

Allegretto

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Preconcert talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, played here by Sergey Khachatryan, suffered from one of the most famous musical invectives by the hands of Eduard Hanslick, a top music critic in Vienna. Dmitri Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony was censured from performance for close to a decade. Both are now accepted parts of the repertoire: the Violin Concerto as a crowd-pleasing classic, and the Eighth Symphony as a still-troubling work that presents an unromanticized view of war.

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 35

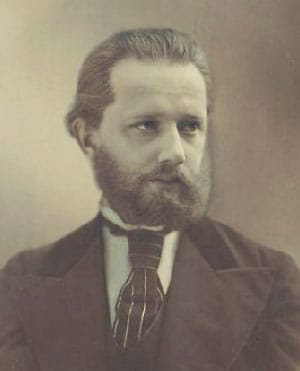

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1878

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1912. Henry Hadley conducted with Efrem Zimbalist as soloist. Most recent—July 2025. Stephanie Childress conducted with Blake Pouliot as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 33 minutes

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote his Violin Concerto during a complex period of his life, a time of deep reflection and remembrance. Although they never officially divorced, his 1877 marriage to Antonia Ivanovna Milyukova fell apart within two months. Tchaikovsky’s sexuality as a gay man has been extensively researched and written about, and he married Milyukova only under duress in the first place. The dissolution had a deep and lasting impact on the composer’s psyche, causing (among other things) depression, impaired creativity, and an insatiable wanderlust. In particular, the following eight years, from 1877–85, were a time of constant travel throughout Europe.

The failure of his marriage was somewhat ameliorated by a new and more lasting epistolary relationship between the composer and his longtime patroness, Nadezhda von Meck. She first wrote to the composer in 1877, and although they never met in person, as was their agreement, her patronage spanned 13 years and 1,200 letters. It is thanks to these letters that we know so much about Tchaikovsky’s inner life.

It was due to von Meck’s largesse that Tchaikovsky spent the summer of 1878 in Clarens, Switzerland, a small resort near Lake Geneva (incidentally, Clarens was also where Stravinsky later wrote The Rite of Spring and Pulcinella). Tchaikovsky wanted to retreat from the world following his marriage fiasco, and try to find his musical voice once again. During this time, a former student, violinist Iosif Kotek, came to visit. Kotek, who was studying in Berlin with the famous violinist Joseph Joachim, had been an intermediary between Tchaikovsky and von Meck. The two played through many violin pieces together, including Eduoard Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole. Tchaikovsky was enormously inspired by this “Spanish symphony” and decided to begin work on a violin concerto himself.

The concerto famously endured one of the most brutal invectives in music history from Eduard Hanslick, a famously opinionated Viennese critic, aestheticist, and historian. Hanslick was a champion of Brahms, whose own violin concerto had been premiered in Vienna just a few years earlier. Hanslick wrote that after Tchaikovsky’s inoffensive opening, “soon vulgarity gains the upper hand and asserts itself to the end of the first movement. The violin is no longer played; it is pulled, torn, made black and blue.” This is likely regarding the emphatically virtuosic triple stops that can indeed sound belabored in certain hands. Hanslick continued that the Adagio is on its best, “winning” behavior. But the finale is another story. He wrote:

[It] breaks off to make way for a finale that transfers us to a brutal and wretched jollity of a Russian holiday. We see plainly the savage vulgar faces, we hear curses, we smell vodka. Friedrich Vischer once observed, speaking of obscene pictures, that they stink to the eye. Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto gives us for the first time the hideous notion that there can be music that stinks to the ear.

It is unclear whether Hanslick ever revisited this concerto or expressed changing opinions of the piece as it gained traction among the violinists of the day. What is clear is that this review deeply affected Tchaikovsky, who is said to have quoted it from memory for the rest of his life.

The composer was also upset that several Russian authorities on violin music refused to play the piece, including its dedicatee, Leopold Auer. Tchaikovsky wrote that Auer had “played all manner of dirty tricks” on him by calling the piece unplayable and claiming it made a “mockery of the public.” Similarly, Kotek refused to play the piece in public, despite having advised on its composition and having helped to compose the first movement cadenza. Tchaikovsky wrote in a letter how grateful he was to Adolf Brodsky for being the “heroic” violinist to premiere the work, four years after its composition. In another he stated, “I don’t fare well with the critics,” and noted how deeply touched he was by Brodsky’s valiant premiere.

Thankfully for today’s audiences, the violin concerto has become one of the most standard pieces of the repertoire, often played and much beloved. Far from being unplayable, precocious violinists learn it at a young age and perform it regularly.

The Music

The first movement begins with a short, gentle introduction, then the violin enters with a quasi-improvisatory passage that transitions into the first theme of the movement. One of the main transition motifs is the use of chromatic scales to move from one passage to the next. The violinist plays several expository iterations of this first theme and the second theme, which builds into a massive orchestral reprisal of the first theme. The violin leads the orchestra through a short development (with many similarities to the first movement of the Fourth Symphony, which the composer would soon complete), until the orchestra takes back over with the first theme again, cueing up a massive cadenza. Interestingly, Tchaikovsky wrote out the whole cadenza, shifting away from the practice of letting the soloist perform their own. The orchestra returns with a duet between the soloist and flute. Finally we arrive at the coda, which was written at a time when silent audiences were not the common practice. It is all but impossible to sit quietly in one’s seat at the end of this thrilling race to the end.

The second movement opens with a wind chorale, tinted by melancholy and nostalgia. This sets the tone for the more introverted movement, and meanders from one theme to the next and back again. Rather than ending decisively as in the first movement, the second movement transitions slowly, portentously, to the final movement. Again, the orchestra leads the charge to the violinist’s entrance. As soon it takes off, Tchaikovsky incorporates elements of Russian folk music, including open drones and folk-like melodies. The movement has a more nostalgic middle section, but ends heroically with the first theme, capped off by a quintessential Tchaikovsky-length coda.

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Opus 65

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1943

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1994. Herbert Blomstedt conducted. Most recent—June 2019. Juraj Valčuha conducted.

Instrumentation: 4 flutes (3rd and 4th doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, snare drum, bass drum, and xylophone), and strings

Duration: About 65 minutes

It seems impossible to discuss the symphonic works of Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich without discussing them within their political context, or at the very least, within their politicized reception. Shostakovich is often viewed as a political figure, even an activist, who used his music to flout the rules within his socialist umwelt. But as a composer living in the Soviet Union during both world wars, and one of the few composers of his time equally known internationally as in his homeland, Shostakovich was subjected to immense scrutiny from the socialist regime. Like Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony had a complicated reception at its premiere and has fallen in and out of favor in the 82 years since its first performance.

After the rapturous reception of his Seventh Symphony, the Leningrad, Shostakovich intended to write an opera, a ballet, and an oratorio. But he put those aside to instead begin work on his Eighth Symphony, another of his “War Symphonies,” written during and about World War II. The Seventh Symphony addressed the siege of Leningrad, which lasted almost 900 days and killed nearly half the population of the city. It was immensely popular at its premiere and soon was performed across the Allied countries to show solidarity against the Axis powers.

Shostakovich wrote his Eighth Symphony very quickly, composing the 65-minute work in just over two months during the summer of 1943. He wrote the first movement in Moscow in the beginning of July and spent much of August working on it in Ivonovo, a retreat for Soviet composers away from the dangers and distractions of the war. While he was there, Shostakovich resided and worked in a converted henhouse. Perhaps not the pinnacle of luxury, but it served as an ideal contemplative space for him to rest and compose. He finished the symphony by September 9.

The Music

There are many unusual elements in the Eighth Symphony, unsurprising for Shostakovich given the enormous expectations in the wake of the Seventh’s popularity. The Eighth has five movements, the first of which is longer than the next three movements combined. The two fast movements are scherzo-like, but skew toward mock-militarism and anxiety rather than humor, followed by an oddly unmusical slow movement and a pastoral finale. The symphony starts in C minor and ends in C major, evincing the trope of the “heroic symphony” as found in Beethoven’s Fifth and Mahler’s Second. However, far from evoking joy, triumph, and ascension as in those, Shostakovich’s finale sounds almost like a sigh of resignation—not a propagandistic triumph of the Soviets over the Nazis, but the banal return to quotidian life, as if the war had never happened in the first place.

Evgeny Mravinsky, the symphony’s dedicatee, conducted the premiere on November 4, 1943, in the Great Hall at the Moscow Conservatory. Mravinsky wrote that “the daring orchestration matches the innovation of the symphony,” noting that “Shostakovich had perfect orchestral hearing. He heard everything … both in his head and in the real sounding.” Unfortunately the audience at the premiere did not find as much clarity in the symphony as had the composer.

It seems that many of the listeners found the work confusing, maybe even a bit obtuse. Some, like Shostakovich’s dear friend Ivan Sollertinsky, declared the Eighth even better than the Seventh. The composer Boris Asafyev compared its impact to that of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth. But months after the premiere, at the Plenum of the Organizing Committee of the Union of Composers (which surveyed the works of Soviet composers during the war), Sergei Prokofiev was more typical in criticizing what he saw as its excessive length and weak melodic material.

Shostakovich, like many other composers from the Soviet era, was at times deemed a degenerate, at others lauded for his socialist realist masterworks, all according to the political will of the Soviet Union. Shostakovich scholar Laurel Fay writes, “Shostakovich’s failure to limn the psychological climate—to provide an optimistic, even triumphant finale—was a letdown to those inclined to read the symphony, like its predecessor, as an authentic wartime documentary.” In 1948, Shostakovich saw his favor with the Soviet leadership sour. During the war, Soviet leadership had focused all its energies on the Eastern Front, rather than on enforcing its desire for “socialist realism” in the arts. In “socialist realism,” composers were expected to write music that portrayed the idealism of socialism and performed a didactic role in encouraging listeners to adhere to socialist expectations. Any music that authorities believed did not follow these maxims by authorities was labeled “formalism,” and deemed unfit to perform. Andrei Zhdanov, an important acolyte of Stalin’s, was tasked with rooting out all formalist composers. Shostakovich found himself among them as part of the Zhdanov Decree. Not only was his Eighth Symphony among the pieces banned from performance, but he was also dismissed from the Moscow Conservatory, an important source of income. Thankfully, Shostakovich’s reputation was rehabilitated during Krushchev’s post-Stalin thaw in 1958, and his Eighth Symphony found a place on concert hall stages again.

The lukewarm reviews, composers’ plenum debate, and Zhdanov decree probably tell us more about the effects of state oversight and control than about the Eighth Symphony itself. It is impossible to know what Shostakovich’s output would have been if the Stalin regime had not put such pressure on him to compose in a certain way. Even so, it is important to remember that Shostakovich was censured—and on multiple occasions came close to enduring far worse—for composing music that he must have known would be provocative.

Despite being a piece that follows the “heroic journey” of minor to major key, the Eighth Symphony is not, and perhaps, should not be a joyful experience. It is not written as a piece for leisurely listening, but rather a white-knuckled ride through the depths of despair, condemnation, mockery, anger, grief, and eventually, an exhausted, cathartic sigh. It can be interpreted as a political act against the expectations of socialist realism, against valorizing war and the victories on the Eastern Front, and evoking the pain, suffering, and misery that war inflicts on ordinary citizens. Experiencing music like this can feel like work. That is perhaps exactly how it should feel.

—Alicia Mastromonaco

About the Artists

David Afkham

David Afkham is chief conductor and artistic director of the Spanish National Orchestra and Chorus, a position he has held since September 2019, after serving as the orchestra’s principal conductor beginning in 2014. Highlights of his 2025–26 season include a Japanese tour with the NHK Symphony, his debut with the Lucerne Symphony, and appearances with the Minnesota Orchestra, Tonkünstler Orchestra, Deutsche Oper Berlin, and Seattle Opera. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Other appearances include the Cleveland Orchestra, Boston Symphony at Tanglewood, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Staatskapelle Berlin, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, and Orchestre National de France, among many others.

Born in Freiburg, Germany, Afkham began piano and violin lessons at an early age. He went on to study piano, music theory, and conducting at the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, before continuing his studies at the Hochschule für Musik “Franz Liszt” Weimar. Afkham was the first recipient of the Bernard Haitink Fund for Young Talent and assisted Haitink on several projects, including complete symphonic cycles with the Chicago Symphony, Concertgebouw Orchestra, and London Symphony. From 2009–2012, Afkham was assistant conductor of the Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester. He won first prize at the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition in London in 2008 and was the inaugural recipient of the Nestlé and Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award in 2010.

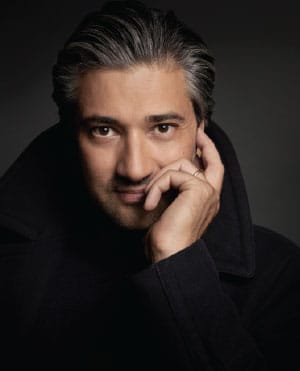

Sergey Khachatryan

This season, Sergey Khachatryan performs with the Cleveland Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Lucerne Symphony, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, Barcelona Symphony and National Orchestra of Catalonia, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, and Taipei Symphony. His recent appearances include the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Seattle Symphony, Toronto Symphony, and Montreal Symphony. He also toured Japan with the Nippon Foundation and performed Beethoven’s Violin Concerto at the Lucerne Festival with the Vienna Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel as the recipient of the Credit Suisse Young Artist Award. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut on a Great Performers Series concert with the touring London Philharmonic in March 2006, and made his debut with the SF Symphony itself in November 2007 as a Shenson Young Artist.

With his sister, pianist Lusine Khachatryan, he released the album My Armenia on the Naïve label, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. That album was awarded an Echo Klassik Award. As a duo, they have also recorded the Brahms violin sonatas, and Sergey’s discography also includes the Sibelius and Khachaturian violin concertos with Sinfonia Varsovia and Emmanuel Krivine and both Shostakovich violin concertos with the Orchestre National de France and Kurt Masur.

Born in Yerevan, Armenia, Khachatryan won first prize at the VIII International Jean Sibelius Competition in Helsinki in 2000, becoming the youngest winner in the history of the competition. In 2005 he claimed first prize at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels. He plays the 1724 “Kiesewetter” Stradivarius violin on a kind loan from the Stretton Society.

Alicia Mastromonaco is a Contributing Writer, Preconcert Speaker, and frequent guest horn for the San Francisco Symphony. She is a member of the California Symphony, Monterey Symphony, and Marin Symphony, and is a horn lecturer at Sonoma State University. She studied at Boston University, UCLA, and earned a PhD in musicology from the University of California, Santa Barbara.