In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, July 10, 2025, at 7:30pm

Frost Amphitheater

Friday, July 11, 2025, at 7:30pm

Davies Symphony Hall

Stephanie Childress conducting

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Selections from The Sleeping Beauty Suite, Opus 66a (1889)

Introduction: The Lilac Fairy (La Fée des lilas)

Adagio: Pas d’action

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 35 (1878)

Allegro moderato–Moderato assai

Canzonetta: Andante

Finale: Allegro vivacissimo

Blake Pouliot

Intermission

Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture (1869/80)

1812 Overture (1880)

Lead sponsorship for the San Francisco Symphony’s performances at Frost Ampitheater provided by The Sakurako & William Fisher Family.

The July 10 performance at Frost Amphitheater is presented as part of Stanford Live’s Summer@Live concert series.

Program Notes

At A Glance

The second half opens with Tchaikovsky’s dramatically sensitive interpretation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, cast as a tragic Fantasy-Overture. This contrasts with his 1812 Overture, now a staple of summer fireworks shows, but originally meant as a sonic monument to Napoleon’s defeat—complete with a Russian prayer, strains of French and Tsarist anthems, and, of course, cannons.

Selections from The Sleeping Beauty Suite, Opus 66a

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1888–89

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1931. Issay Dobrowen conducted the complete suite for the Standard Hour Radio Broadcast. Most recent—July 2009. James Gaffigan conducted the complete suite.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 cornets, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, bass drum, glockenspiel, and tam-tam), harp, and strings

Duration: About 10 minutes

When Ivan Vsevolozhsky, director of Saint Petersburg’s Imperial Theater, approached Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky about writing a ballet, he suggested that the subject be Undine, the doomed water-sprite. Tchaikovsky reported to his publisher in November 1886 that he had agreed to the Undina commission and that it would figure in the next ballet season, but in the end it came to naught. Vsevolozhsky got a masterpiece nonetheless: The Sleeping Beauty, which he proposed once he sensed that Undina was not likely to happen. When Tchaikovsky received Vsevolozhsky’s draft of a libretto, derived from Charles Perrault’s famous 17th-century fairy tale La belle au bois dormant, he responded: “I am pleased to tell you that I am charmed, delighted beyond all description. It suits me perfectly, and I could ask for nothing better to set to music.”

So great was the excitement about the new ballet that the tsar himself attended the dress rehearsal; at the end, his only comment to the composer was “Very nice.” The next day, the audience responded with similar tepidity, but before long, The Sleeping Beauty became rightly regarded as not only the most substantial of Tchaikovsky’s three ballets, but indeed as the work that most perfectly defines the essence of classical ballet.

The Introduction is the brief overture to the ballet. The Adagio: Pas d’action is the finale of the Suite: in the original production, the princess Aurora hands roses to four princes who are courting her, which is why it became known as the “Rose Adagio.”

—James M. Keller

Violin Concerto in D major, Opus 35

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Work Composed: 1878

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1912. Henry Hadley conducted with Efrem Zimbalist as soloist. Most recent—September 2023. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted with Leonidas Kavakos as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 33 mins

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto is as indispensable to violinists as his B-flat minor piano concerto is to the keyboard lions. Each work got off to a dismaying start. The piano concerto, completed early in 1875, was rejected by Nicolai Rubinstein in the most brutal terms and had to travel to faraway Boston for its premiere. Three years later, the painful episode repeated itself with the violin concerto, which was turned down by its dedicatee, the influential concertmaster of the Imperial Orchestra in Saint Petersburg, Leopold Auer.

From the beginning, Tchaikovsky had intended the concerto for Auer. Here is the story as Auer told it to The Musical Courier, writing from Saint Petersburg on January 12, 1912:

When Tchaikovsky came to me one evening, about thirty years ago, and presented me with a roll of music, great was my astonishment on finding that this proved to be the Violin Concerto, dedicated to me, completed, and already in print. My first feeling was one of gratitude for this proof of his sympathy toward me, which honored me as an artist. On closer acquaintance with the composition, I regretted that the great composer had not shown it to me before committing it to print. . . . It is incorrect to state that I had declared the concerto in original form technically unplayable. What I did say was that some of the passages were not suited to the character of the instrument, and that, however perfectly rendered, they would not sound as well as the composer had imagined.

Nicolai Rubinstein had eventually come around in the matter of the piano concerto, and Auer not only became a distinguished exponent of the violin concerto but taught it to his remarkable progeny of pupils—Jascha Heifetz, Efrem Zimbalist, and others. But his initial rejection was a practical nuisance. His verdict, wrote Tchaikovsky, “had the effect of casting this unfortunate child of my imagination into the limbo of the hopelessly forgotten.” And hence the delayed premiere in a far-off and unsympathetic place.

The first performance went to Adolf Brodsky, who turned 30 in 1881, was of Russian birth, but trained chiefly in Vienna. He had already tried to place Tchaikovsky’s concerto with the orchestras of Pasdeloup and Colonne in Paris before he managed to persuade Hans Richter and the Vienna Philharmonic. The performance must have been awful. Brodsky himself was prepared, but Richter had not allowed enough rehearsal time, and most of the little there was went into correcting mistakes in the parts. The orchestra, out of sheer timidity, accompanied everything pianissimo. Brodsky was warmly applauded, but the music itself was hissed. What is best remembered about the premiere is Eduard Hanslick’s review:

The violin is no longer played; it is tugged about, torn, beaten black and blue. . . . We see a host of savage, vulgar faces, we hear crude curses, and smell the booze. In the course of a discussion of obscene illustrations, Friedrich Vischer once maintained that there were pictures which stink to the eye. Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto for the first time confronts us with the hideous idea that there may be music that stinks to the ear.

The Music

It is impossible to please everybody. But Tchaikovsky pleases us right away with a gracious melody, minimally accompanied, for the violins of the orchestra. Indeed, we had better enjoy it now, because he will not bring it back. But as early as the ninth measure, a few instruments abruptly change the subject and build up suspense with a quiet pedal tone. The violins at once get into the spirit of this new development, and they have no difficulty running over those few woodwinds who are still nostalgic about the opening melody. And thus the soloist’s entrance is effectively prepared. What he plays at first is the orchestral violins’ response to the pedal tone, but set squarely into a harmonic firmament and turned into a “real” theme. Later, Tchaikovsky introduces another theme for the solo violin, quiet but con molto espressione. The transitional passages provide the occasion for the fireworks for which the concerto is justly famous. The cadenza is Tchaikovsky’s own, and it adds interesting new thoughts on the themes and provides further technical alarums and excursions.

At the first run-through in April 1878, everybody, Tchaikovsky included, sensed that the slow movement was not right. He quickly provided a replacement in the form of the present canzonetta. It is lovely indeed, both in its melodic inspiration and in its delicately placed, beautifully detailed accompaniments.

Perhaps with his eye on the parallel place in Beethoven’s violin concerto, Tchaikovsky invents a dramatic crossing into the finale, though unlike Beethoven he writes his own transitional cadenza. So far we have met the violin as a singer and as an instrument that allows brilliant and rapid voyages across a great range. Now Tchaikovsky presents it to us with the memory of its folk heritage intact. We can read Hanslick again and recognize what he is talking about when he is so offended. Tchaikovsky’s finale sounds to us like a distinctly urban, cultured genre picture of country life, but one can imagine that in the context of 1881 Vienna it might have struck some delicate noses as pretty uncivilized.

—Michael Steinberg

Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Work Composed: 1869 (rev. 1880)

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 12, 1913. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—September 2014. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted at the Opening Gala.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 21 minutes

In the winter of 1868–69, Tchaikovsky was, for the only time in his life, attracted to a woman, Désirée Artôt, a Belgian soprano. Tchaikovsky’s intentions were serious, but Artôt suddenly brought their relationship to an end by marrying a baritone colleague of hers. When Tchaikovsky next saw her on the stage he wept all evening.

Tchaikovsky was ready to have the composer Mily Alexeievich Balakirev tell him to write a work based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, which is indeed what Balakirev did, going so far as to tell Tchaikovsky how to do it, proposing a key scheme and even writing out four measures of music to show how he would begin such a piece. Balakirev was not always pleased with the way Tchaikovsky worked out “his” ideas. At first, only the broad love theme aroused his enthusiasm. It is “simply delightful,” he wrote. “There’s just one thing I’ll say against this theme, and that is that there’s little in it of inner, spiritual love, only a passionate physical languor (with even a slightly Italian hue), whereas Romeo and Juliet are decidedly not Persian lovers but European.” Balakirev continued to comment, suggest, blame, and praise, and Tchaikovsky continued to compose—buoyed by the praise, stimulated by the blame, and becoming more confident in his themes and more imaginative in his reading of the play.

He listened carefully at the premiere, which was an indifferent success. That summer he subjected his overture to drastic revisions, finding the present evocative beginning, devising a stronger close, articulating more vividly what came between. Ten years later he returned to Romeo and Juliet, and it was then that he found the superb coda. Again, he put strong ideas in place of weak, he integrated, he refined. And he produced a masterpiece.

—M.S.

1812 Overture

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Work Composed: 1880

SF Symphony Performances: First—Jaunary 1913. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—July 2012. Michael Francis conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tambourine, snare drum, bass drum, chimes), cannons, and strings

Duration: About 16 minutes

Program annotators like to quote composers. Tchaikovsky, however, makes it difficult. Here he is, writing to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck on October 10, 1880: “The Overture will be very loud, noisy, but I wrote it without any warm feelings of love, and so it will probably be of no artistic worth.” The Overture, of course, was 1812. Tchaikovsky wrote it for the All-Russian Art and Industrial Exhibition in Moscow—the Cathedral of the Redeemer, built in commemoration of the victory over Napoleon in 1812, was to be consecrated during the exhibition, and that is where Tchaikovsky got the idea for his Overture, which was first heard in Moscow on August 20, 1882.

Battle pieces have been popular at least since the 16th century. For instance, no piece brought Beethoven a greater public success than his depiction of the Duke of Wellington’s victory at the Battle of Vitoria. Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture fits right into the tradition. He paints an evocative religious backdrop, gives us a vivid battle scene, concludes with the vanquishing of the Marseillaise by General Alexei Lvov’s splendid Tsarist anthem, and celebrates victory with the most Russian of sounds, the tolling of bells. Besides the two national anthems, he quotes a church hymn, a folk song, and his own early opera The Voyevoda, the source of the energetic second theme of the Allegro. We need not agree with Tchaikovsky’s own harsh assessment of 1812, but we do have to concede that it is loud.

—M.S.

About the Artists

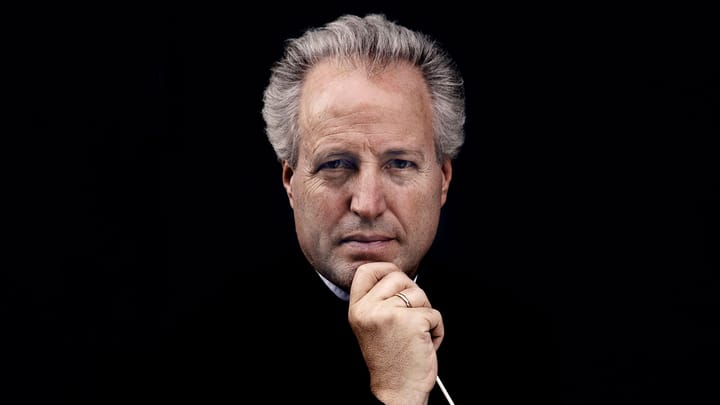

Stephanie Childress

Stephanie Childress began her tenure this season as principal guest conductor of the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra and National Orchestra of Catalonia, and returned to the Cleveland Orchestra, New World Symphony, Utah Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra, Orchestre National d’Île-de-France, and Opéra Orchestre National de Montpellier. She also debuted with the Royal Philharmonic, Hallé, Royal Northern Sinfonia, and MDR Symphony Leipzig. From 2021 to 2023, she was assistant conductor of the St. Louis Symphony under Stéphane Denève, during which time she led multiple subscription concerts. Last season saw her debut with the Cleveland Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, and Minnesota Orchestra. She is currently the associate conductor of the Sun Valley Music Festival and artistic director of the Sun Valley Music Festival Institute.

The Franco-British conductor enjoys a close relationship with the French cultural scene, following her second-prize win at the 2020 inaugural La Maestra conducting competition. Since then, she has conducted Orchestre de Paris, Paris Mozart Orchestra, and Orchestre de Chambre de Paris. In September 2023, after being one of the first conducting fellows of l’Académie de l’Opéra National de Paris, she made her debut at the Palais Garnier with l’Orchestre Pasdeloup for the ballet company’s opening gala. She makes her San Francisco Symphony debut with this performance.

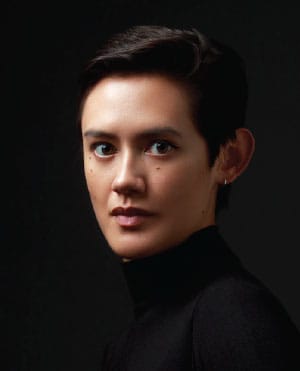

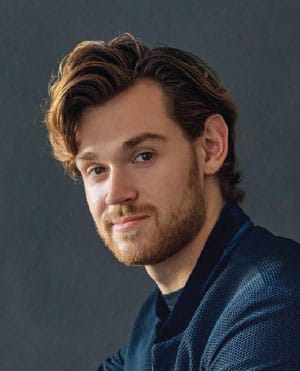

Blake Pouliot

Blake Pouliot’s recent highlights include debuts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, San Diego Symphony, Houston Symphony, London Philharmonic, and Chamber Orchestra of Europe. This past season he made recital debuts at Carnegie Hall and La Jolla Music Society, and returned to the Seattle Chamber Music Society. Between 2020–21, he was soloist in residence with the Orchestre Métropolitain with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, which led to his debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 2022.

Since his orchestral debut at age 11, Pouliot has also performed with the Aspen Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Toronto Symphony, and Seattle Symphony. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in July 2019 and performs on a 1729 Guarneri del Gesù on generous loan from an anonymous donor. He released his debut album, of 20th century French music, on Analekta Records in 2019, receiving five stars from BBC Music Magazine and a 2019 Juno Award nomination for Best Classical Album.