In This Program

The Concert

Wednesday, May 21, 2025, at 7:30pm

Tony Siqi Yun piano

Johannes Brahms

Theme and Variations in D minor, Opus 18b (1861)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Opus 57,

Appassionata (1806)

Allegro assai

Andante con moto

Allegro ma non troppo–Presto

Ferruccio Busoni

Berceuse from Elegies (1909)

Robert Schumann

Symphonic Études, Opus 13 (1835)

Theme: Andante

Étude I. Un poco più vivo

Étude II.

Étude III. Vivace

Étude IV.

Étude V.

Variation I.

Variation II.

Variation III.

Étude VI. Agitato

Étude VII. Allegro molto

Étude VIII.

Étude IX. Presto possible

Variation IV.

Variation V.

Étude X.

Étude XI.

Étude XII. Finale: Allegro brillante

This concert is performed without intermission.

Program Notes

Theme and Variations in D minor, Opus 18b

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1859–61

The opus number 18 will jump out as a familiar entry in Johannes Brahms’s catalogue; it designates his String Sextet No. 1, a much-loved work he composed in 1859–60. Opus 18b signifies a different version of that work, but not of the entire piece. It is the composer’s own solo-piano adaptation of just the second movement of the Sextet.

When Brahms sent the String Sextet to his violinist-colleague Joseph Joachim, asking for his comments, he concluded his letter with the sort of self-deprecating remark one encounters recurrently in his communications: “I look forward to being invited soon to a rehearsal. However, if you don’t like the piece, then by all means send it back to me.” Joachim and five of his colleagues played the premiere on October 20, 1860, in Hanover, and then a second performance took place shortly thereafter at Joachim’s home, when the Hanoverian ambassador to Vienna attended as guest of honor. On the morning of November 27, Joachim and his friends played it at the Leipzig Conservatory, where according to Clara Schumann, it “roused decided enthusiasm.”

Set at a moderately slow pace, the theme is built on a harmonic foundation that greatly resembles the folia, a progression (usually encountered in the key of D minor, as here) that was hugely popular from the late Renaissance through the Baroque era. In its pure form, the folia was in triple meter, but Brahms changes it to duple. He states the theme and then presents five variations. The first three maintain the same tempo but sound as if they become progressively faster, since Brahms fills their beats with more and more notes—16th notes in the first variation, 16th-note triplets in the second, 32nd notes in the third . . . which, surprisingly, cadences in the major mode to launch the fourth variation. Here Brahms marks molto espressivo e legato (very expressive and smooth) as the music pours forth as a sort of chorale. The major mode maintains for the fifth variation, mostly set in a high register, after which the piece concludes in a D-minor coda that echoes, but does not exactly duplicate, the original statement of the theme, working in references to some of the rhythmic ideas from the preceding variations.

Clara Schumann, who was one of her era’s leading pianists, had admired the piece from its inception on, and Brahms apparently surprised her by making this solo-piano arrangement of its second movement. Its title read “Theme and Variations for Pianoforte, arranged for Clara Schumann on September 13, 1860, as a friendly greeting.” The date was her 41st birthday.

Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Opus 57, Appassionata

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1804–06

The nickname of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Appassionata dates only to 1838, when the Hamburg publisher Cranz released a four-hand arrangement. This most tragic of Beethoven’s sonatas is indeed passionate, even if its passion emanates from an emotionally forbidding place.

In 1839, Carl Czerny, the creator of endless piano exercises, published a guide titled On the Proper Performance of Beethoven’s Complete Works for Solo Piano. He declared his qualifications, writing in the third person: “[He] trusts he is so far competent thereto, from having in his early youth (from the year 1801) received instruction from Beethoven in pianoforte playing—studied all his works with great predilection, on their first appearance, and many of them under the Master’s own guidance.” He considers the sonatas chronologically, addressing matters of technique that arise in the each, but he also shares some more general observations. He says of Opus 57: “Beethoven himself considered this as his greatest Sonata, up to the period when he had composed his Opus 106 [Hammerklavier], and certainly it is even now to be regarded as the most complete development of a powerful and colossal idea. The same physical and mental powers which the player has had to develop for the performance of most of the Sonatas previously . . . must be here dispensed in a two-fold degree, in order worthily and with full effect to unfold the beauties of the noble musical picture.”

The first movement begins in murky, minor-key depths but pianissimo is soon interrupted by outbursts of fortissimo; this movement can turn on a dime. “In the first movement of this sonata,” reads a review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of April 1, 1807, “he has once again let loose many evil spirits . . . however, it is here worth the effort to struggle not only with the wicked difficulties, but also with many . . . peculiarities and bizarreries!” The slow movement is a major-key eye of the hurricane, a theme with five variations, the first syncopated, the second gently flowing, the third lyrical but with a fluttering accompaniment, the fourth approaching the simplicity of the unadorned theme. A few measures of transition connect this without a break to the athletic third movement. It seems to have used up all available energy when, less than a minute from the end, the tempo ramps up to Presto for a scorching conclusion. Czerny wrote of this finale: “Perhaps Beethoven (who was ever fond of representing natural scenes) imagined to himself the waves of the sea in a stormy night, whilst cries of distress are heard from afar—such an image may always furnish the player with a suitable idea for the proper performance of this great musical picture.”

Berceuse from Elegies

Ferruccio Busoni

Born: April 1, 1866, in Empoli, Italy

Died: July 27, 1924, in Berlin

Work Composed: 1909

Ferruccio Busoni was one of the towering pianists of his time, acclaimed for a monumental style marked by incisive attacks and magnificent sonority. He tended to downplay his activities as a pianist, preferring to think of himself as a composer first and foremost. He also gained fame—or notoriety—as an essayist. “As much a virtuoso of the pen as of the piano,” wrote his biographer Antony Beaumont, “Busoni commended a literary style capable of the same variety of attack and nuance for which he was renowned as a musician.” His writings reached their pinnacle in his Outline of a New Esthetic of Music, published in 1907 and released in a revised edition in 1915. This collection of thoughts provided much fodder for argument among intellectuals. A sample idea: “Feeling is born of six ‘graces’—Taste, Style, Economy, Temperament, Intelligence and Balance. Out of these elements emerges Individuality.”

He was therefore viewed as a leading thinker of musical Germany when, in 1907–08, he produced a set of six contrasting piano pieces he titled Elegies. The critics let loose when he played their premiere, in March 1908; one termed the set “a veritable source of dismay.” In June 1909, Busoni composed his Berceuse (Lullaby) for piano, which he would append to the existing six pieces, bringing the complete Elegies set to seven when it was republished that year. As one might expect of a lullaby, the left hand often concentrates on a “rocking” motif, in this case consisting of widely spaced eighth-note octaves or rolling triplets. Although these figures anchor the piece at least temporarily on a tonic note, the harmonic behavior is free-wheeling; and even the idea of a tonic is far from straightforward, since the tonic at the beginning is clearly F and at the end something having to do with C. An entire page unfurls under the instruction sempre i due Pedali tenuti (the two pedals always held down), with the right hand playing in one key, the left in another, the two parts fusing together into a mysterious wash of sound.

For a while Busoni contemplated recasting his piano Berceuse into a work for violin and piano. He let go of that idea, but he did transform it into one of his finest orchestral pieces, the Berceuse élegiaque. This he did in October 1909, on the heels of his mother’s death. He was explicit about the funerary inspiration of the symphonic Berceuse élegiaque, even to the extent of affixing the subtitle “Des Mannes Wiegenlied am Sarge seiner Mutter” (The Man’s Lullaby at his Mother’s Coffin). What’s more, he introduced the piece with a quatrain of poetry he had written, which may also be à propos to the originally piano setting:

The child’s cradle rocks,

The hazard of his fate reels;

Life’s path fades,

Fades away into the eternal distance.

Symphonic Études, Opus 13

Robert Schumann

Born: June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Germany

Died: July 29, 1856, in Endenich, Germany

Work Composed: 1834–35

When Robert Schumann was 18, he traveled to Leipzig, where he planned to enter law school. During that visit he made the acquaintance of Friedrich Wieck, a well-known piano teacher, and his talented nine-year-old, piano-playing daughter, Clara. Plans for law school fizzled, and in September 1830 Robert became Wieck’s full-time piano pupil, moving into his home the next month. Robert fell in love with Ernestine von Fricken, another Wieck student, and they were engaged in September 1834. In the spring of 1835, he suddenly found himself falling for Clara, now 15 years old, and following their first kiss that November he ended his engagement with Ernestine. His Symphonic Études are a remnant of his Ernestine phase; they are variations of a theme composed by her guardian, and then adoptive father, Baron von Fricken, an amateur flutist and a composer of limited inspiration.

The piece underwent a circuitous evolution. In the winter of 1834, Schumann composed 16 variations on the Baron’s tune. Only 11 of these made it into the work’s original publication, in 1837, where they are followed by a finale based on an unrelated theme by the composer Heinrich Marschner. He thought about calling the work Variations pathétiques and then Etuden im Orchestercharakter von Florestan und Eusebius (Études of an Orchestral Character by Florestan and Eusebius). Feisty Florestan and dreamy Eusebius were the imaginary friends Schumann invented to serve as mouthpieces for conflicting viewpoints in his music reviews; perhaps he unhitched their names from this work because Florestan elbowed Eusebius so much out of the way. In any case, the 1837 publication was titled Twelve Symphonic Études for Piano. Fifteen years later, in 1852, a new edition appeared in Leipzig with the title Études en forme de variations; two of the variations were excised and some changes were made in the others. In 1873, the five variations Schumann had omitted from his 1837 edition were published as an Anhang (Appendix), with Clara’s blessing and probably edited by Brahms. Pianists preparing to perform the Symphonic Variations must decide which movements to include. In this recital, Tony Siqi Yun plays all of the originally published movements, into which he inserts the first three Anhang Variations between Études V and VI, and the remaining two between Études IX and X.

Each étude presents challenges of technique as well as of musical conception. The set is filled with extraordinary coloristic effects: in Étude II, for example, treble and bass lines (the latter playing the theme) are widely separated, with fluttering chords spaced between them—validating why Schumann considered naming the set Études of an Orchestral Character. Étude III hardly seems like piano music at all; at a few places it apparently occupies all three of the pianist’s hands. Étude IV is a canon of chords . . . and so on through to the triumphant finale.

—James M. Keller

About the Artist

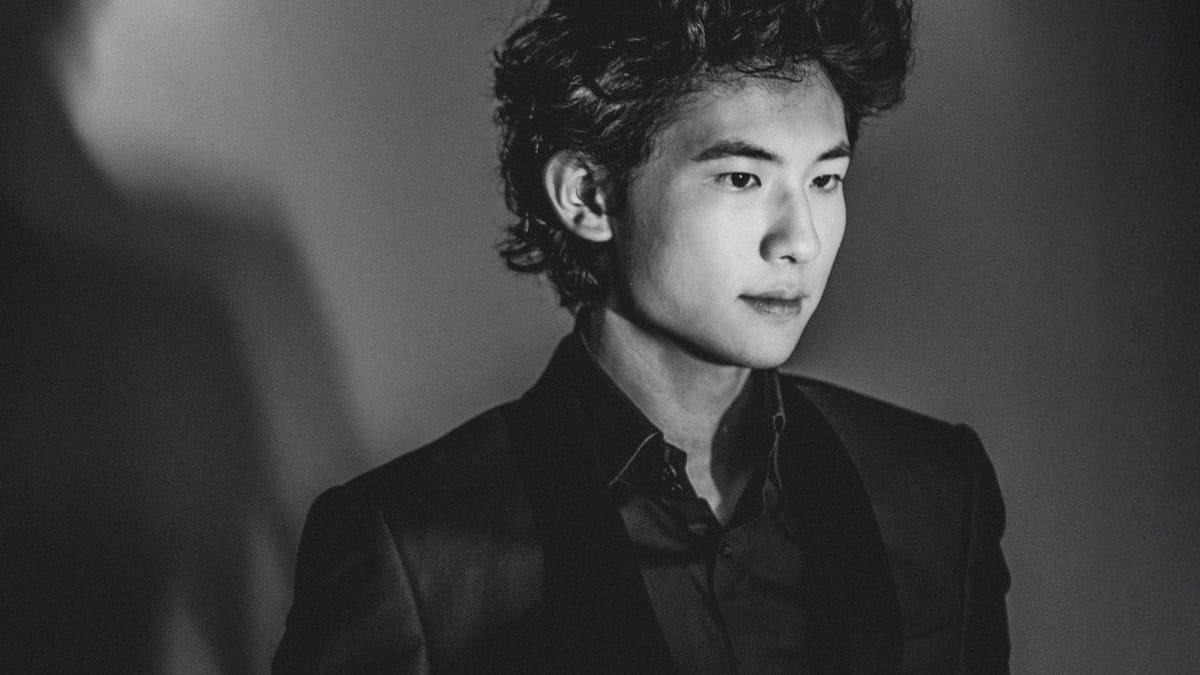

Tony Siqi Yun

Tony Siqi Yun was born in Canada, became a Gold Medalist at the First China International Music Competition in 2019, and was awarded the Rheingau Music Festival’s Lotto-Förderpreis in 2023. In recent seasons, he has debuted with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic, Rhode Island Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony, New Jersey Symphony, Edmonton Symphony, Chamber Orchestra of Paris, Shanghai Symphony, and performed at the Colorado Music Festival, Aspen Festival, and Vail Dance Festival. He has also toured the United States and performed at Carnegie Hall with Montreal’s Orchestre Métropolitain.

Yun regularly gives recitals in both North America and Europe. Recent and future highlights include debuts at the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Düsseldorf Tonhalle, Luxembourg Philharmonie, Stanford Live, Gilmore Rising Stars Series, and 92nd Street Y. He is a recipient of the Jerome L. Greene Fellowship at the Juilliard School, where he studied with Yoheved Kaplinsky and Matti Raekallio. He makes his debut at the San Francisco Symphony with this recital.

Learn more about Tony Siqi Yun.