In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, October 30, 2025, at 7:30pm

Conner Gray Covington conducting

San Francisco Symphony

Vertigo

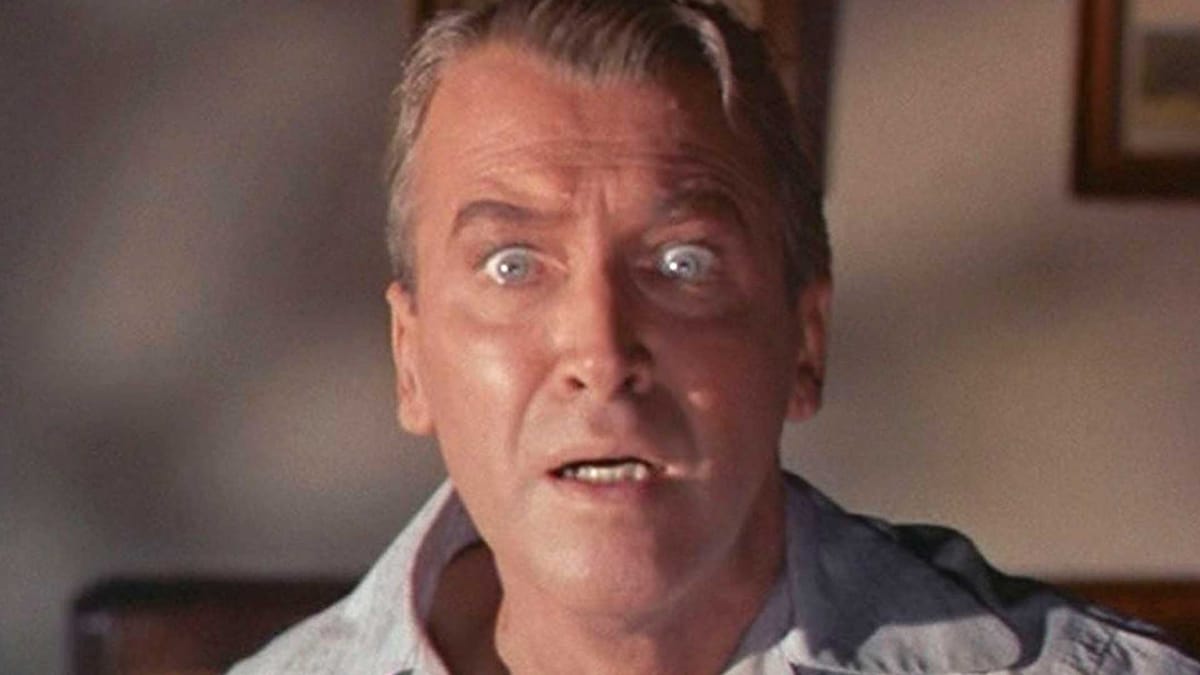

James Stewart John “Scottie” Ferguson

Kim Novak Madeleine Elster / Judy Barton

Barbara Bel Geddes Midge Wood

Tom Helmore Gavin Elster

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Associate Producer Herbert Coleman

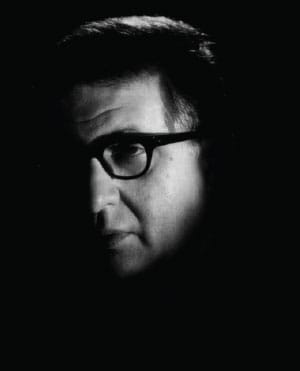

Music by Bernard Herrmann

Screenplay by Alec Coppel Samuel A. Taylor

There will be one intermission.

© 2025 Universal Studios. All Rights Reserved.

© 1958 by Alfred J. Hitchcock Productions, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Producer: John Goberman

Live Orchestra Adaptation by Pat Russ

Technical Supervisor: Pat McGillen

Music Preparation: Larry Spivack

The producer wishes to acknowledge the contributions and extraordinary support of John Waxman (Themes & Variations).

A Symphonic Night at the Movies is a production of PGM Productions, Inc. (New York) and appears by arrangement with IMG Artists.

This concert is presented in partnership with

Vertigo Concert Sponsor

The Board of Governors of the San Francisco Symphony gratefully acknowledges the support of the San Francisco Arts Commission.

Music for A City

In founding the San Francisco Symphony in 1911, San Francisco’s civic leaders sought to create a permanent orchestra in our music-loving city. For more than 85 years, the San Francisco Symphony has partnered with the San Francisco Arts Commission to enrich and serve its vibrant community through music. The partnership dates back to 1935, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt encouraged all cities to support local symphonies believing that music was good for the soul of the people. San Franciscans followed suit and passed an historic charter amendment allocating funds to support the Symphony.

Through this mutually beneficial partnership, the Arts Commission funding contributes to the Symphony’s community programs, supports concerts such as Día de los Muertos and Lunar New Year, and helps bring a broad audience to experience its music and programs. This partnership also enables the Arts Commission to distribute funds to support and strengthen cultural equity throughout the city.

The San Francisco Symphony is honored to partner with the San Francisco Arts Commission to continue its work as San Francisco’s orchestra.

Program Notes

Vertigo: Of Romance and Obsession

When Vertigo was released in 1958, the reception was lukewarm. In 2012, it headed the list of the British Film Institute’s survey (held once every decade) of the greatest films ever made, for the first time in 50 years displacing Citizen Kane (a film for which Bernard Herrmann also wrote the music). Vertigo sinks into a viewer’s consciousness and creates a kind of obsession—not as relentless as that which torments its protagonist, but persistent all the same. The film’s fans become Vertigo addicts, glossing over its occasional bursts of overacting and improbable dialogue, captivated by this dark tale of a man bent on retrieving the past, captivated also by the ghostly beauty of the film’s setting, in a San Francisco that looks so different from the one we know, and yet so like it.

Vertigo, drenched in Bernard Herrmann’s most haunting music, was the composer’s own favorite among the seven scores he wrote for Alfred Hitchcock. For those unfamiliar with the film and its plot, here is a brief account (spoilers ahead).

John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart), a San Francisco detective, retires from the police force after suffering an attack of vertigo during a rooftop chase in which he is unable to keep a colleague from falling to his death. Scottie’s friend Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) hires him to shadow his wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak). Madeleine is convinced she is the reincarnation of Carlotta Valdez, a tragic figure from the days of old California who succumbed to madness and took her own life. Scottie falls in love with Madeleine and is devastated when she leaps to her death from the bell tower at Mission San Juan Bautista, his vertigo having rendered him incapable of pursuing her up the stairs and holding her back.

When Scottie meets Judy Barton, he thinks he may have found a way to distract himself from thoughts of Madeleine. Soon he perceives a strange resemblance between Judy and his dead love. Obsessed with Madeleine, he insists that Judy dress as Madeleine dressed, dye her hair the color of Madeleine’s, wear it in Madeleine’s style.

Judy is tortured by guilt. For she is Madeleine—or the woman who posed as Gavin Elster’s wife, whom Elster had killed and whose body Scottie had seen falling from the bell tower, a presumed suicide. One evening Judy makes a mistake that demolishes her cover. Scottie pieces the plot together, forces Judy/Madeleine to drive with him down the coast, and, at San Juan Bautista, drags her with him up the bell tower stairs, struggling with his fear of heights and at last reaching the top. It is night, and when a nun steps from the shadows, Madeleine sees only a dark figure. Terrified, she follows her instinct and runs—out from the bell platform and into the air, plunging to her death. Now Scottie has experienced what one of his doctors had prescribed: a trauma great enough to shock him out of his vertigo. Having reclaimed his life from the tortures of his psyche, he can look down at all he has lost.

The Music

Herrmann later assembled a Vertigo concert suite, and rather than roll through a frame-by-frame commentary on how music and film fit together, consider the three musical episodes in the suite, encompassing the score’s main themes.

Prelude. Saul Bass’s main title credits present us with a series of spherical figures that spiral relentlessly, one morphing into another against a background of shifting colors, lurid and insistent. For this series of visuals, Herrmann creates a musical equivalent. A repeating figure in the strings, colored with chimes and celesta, circles round and round, punctuated by outbursts of brass. As this material broadens in tempo it assumes a romantically dreamy quality. The atmosphere is foreboding. Herrmann’s suite omits the rooftop chase that follows, but listen to the themes presented in that scene, for they will recur throughout the film. Swirling figures evoke the pursuit as the police race after a criminal. In the background lies an early morning vista of the Bay Bridge, fog horns eare voked by low brass. Detective Scottie Ferguson slips, slides down a roof, and catches a gutter, halting his fall. As he looks to the pavement far below, his panic is expressed in a crushing dissonance that shudders with hysterical harp glissandos. When the officer who attempts to help him falls to his death, a last low chord seals this seminal episode.

The Nightmare. Madeleine has jumped to her death from the bell tower. Scottie’s sleep is haunted by distorted memories. We see the cemetery at Mission Dolores, a painting of Carlotta Valdez, then a zoom-in to Carlotta’s bouquet, which comes to life as the flowers assume grotesque shapes and swirl in a motion that draws Scottie in, casting him down a long shaft. A lunging string figure gives way to a Latin rhythm hammered against rising strings and menacing trombones. Winds and brass scream a terrified dissonance as Scottie sees himself falling. He wakes to a grinding note held in the low strings, the same one we heard as we saw Madeleine’s lifeless body atop the tiled roof of the old church.

Scène d’amour. Scottie has spared no expense on Judy’s makeover, essentially turning her into Madeleine. He shops with her for the gray suit that was Madeleine’s favorite, and for shoes like the shoes Madeleine wore. He takes her to a salon to bleach her dark hair Madeleine-blonde. Back at Judy’s apartment, Scottie sees the woman he lost, standing before him now in a ghostly haze. They embrace, and we follow their kiss, starting over her shoulder and then circling them as high strings outline a figure, lovesick and yearning for completion. (“We’ll just have the camera and you,” Hitchcock told Herrmann when he outlined this scene for the composer.) The music grows increasingly prominent, straining and pulling and pushing as it finally swells toward a climax, at which point the circle is complete, the music crests suddenly from minor into major mode—tense, plunging lines open broadly and soar—and the screen goes black. No screen suggestion of love fulfilled has been more breathtaking than this one engineered by Hitchcock and Herrmann.

—Larry Rothe

About the Artist

Conner Gray Covington

Conner Gray Covington leads an unusually broad range of symphonic, opera, and film repertoire ranging from the Classical era to the present day. During his four-year tenure with the Utah Symphony as associate conductor and principal conductor of the Deer Valley Music Festival, he conducted nearly 300 performances of classical subscription, education, film, pops, and family concerts, as well as tours throughout the state. Previously, he was a conducting fellow at the Curtis Institute of Music, where he worked closely with the Curtis Symphony Orchestra, with whom he made his Carnegie Hall debut, while being mentored by Philadelphia Orchestra music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Covington is a five-time recipient of a Career Assistance Award from the Solti Foundation US, and was a featured conductor in the Bruno Walter National Conductor Preview presented by the League of American Orchestras. His recent and upcoming concert engagements include the San Diego Symphony, Tallahassee Symphony, Amarillo Symphony, and Bellingham Festival of Music. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in November 2024.

Born in Louisiana, Covington graduated from the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts in Houston and went on to study violin at the University of Texas at Arlington. He continued his studies at the Eastman School of Music, where he earned a master’s degree in orchestral conducting and was awarded the Walter Hagen Conducting Prize.