In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, November 20, 2025, at 2:00pm

Friday, November 21, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, November 22, 2025, at 7:30pm

Inside Music Talk: Alexi Kenney in Conversation with Benjamin Pesetsky

Thursday: on stage immediately after the performance

Friday and Saturday: on stage at 6:30pm before each performance

Alexi Kenney violin and leader

Olli Mustonen

Nonetto II for Strings (2000)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Barbara Strozzi

(arr. Alexi Kenney)

“Che si può fare,” Opus 8, no.6 (ca. 1664)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Johann Sebastian Bach

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 (ca. 1721)

Allegro

Affettuoso

Allegro

Yubeen Kim flute

Alexi Kenney violin

Jonathan Dimmock harpsichord

Intermission

Antonio Vivaldi

The Four Seasons, Opus 8, nos.1–4 (ca. 1723)

Spring

Allegro

Largo: The Sleeping Shepherd

Allegro: Pastoral Dance

Summer

Allegro non molto

Adagio

Presto

Autumn

Allegro: Songs and Dances of the Country Folk

Adagio molto: The Drunkard Asleep

Allegro: The Hunt

Winter

Allegro non molto

Largo: The Hearth

Allegro

Presenting Sponsor of the Great Performers Series

Thursday matinee concerts are endowed by a gift in memory of Rhoda Goldman.

Inside Music Talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

After that are concertos by two Baroque giants whose music regained popularity in the 20th century: Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 for violin, flute, and harpsichord, and Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons—actually four concertos, and some of the earliest examples of picture-painting in instrumental music.

Baroque Origins

All the music on today’s program lies outside the core orchestral repertoire, at least as it’s generally conceived: large ensemble music combining string and wind instruments from roughly the late 18th century through the mid-20th.

None of it would have been possible, however, without the innovations of the Baroque era: the organizing of common-practice harmony (still how we think about chords in most classical, jazz, and even pop music), the rapid evolution of instrument making (this was the age of Antonio Stradivari, whose instruments can be found today on the San Francisco Symphony stage), and the flourishing of music publishing, which first made classical music into an international industry.

Nonetto II for Strings

Olli Mustonen

Born: 1967, in Vantaa, Finland

Work Composed: 2000

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: string orchestra

Duration: About 15 minutes

Olli Mustonen is a Finnish composer, pianist, and conductor. He has worked in all three roles with orchestras internationally, for many years played in a duo with cellist Steven Isserlis, and has recorded for the Ondine, Bis, Hyperion, RCA, and Decca labels. Mustonen was a composition student of Einojohani Rautavaara, the most prominent Finnish composer after Sibelius. Yet Mustonen’s music seems different than that of most Finnish contemporary composers—warmer, more openly expressive, sometimes embracing homage and neo-Baroque influences.

Nonetto II was originally written for four violins, two violas, two cellos, and bass, with a full string orchestra version following. It seems to inhabit the same sound world we will encounter later on this program with Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons—but with moodier melodic lines and surprising moments of disintegration.

“Che si può fare,” Opus 8, no.6

Barbara Strozzi

(arr. Alexi Kenney)

Born: 1619, in Venice

Died: November 11, 1677, in Padua

Work Composed: ca. 1664

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: solo violin and string orchestra

Duration: About 5 minutes

Baroque music seemed hope- lessly antiquated to musicians of the following generations. Only J.S. Bach and George Frideric Handel, both German composers of the late Baroque, continued to be widely admired and revived prior to the 20th century. Anything earlier was of fringe interest to theorists, at best. So it is not surprising that Barbara Strozzi—a mid-17th-century composer, an Italian, and a woman—was entirely forgotten and went quite literally unsung for 300 years.

Strozzi was born into the rich artistic scene of Venice at a time when music and poetry were mixing into new forms of vocal music. Her father Giulio was a significant literary figure, her mother Isabella Garzoni was his servant. Barbara became a singer, and began publishing her own compositions in 1644, releasing eight volumes of mostly secular vocal music over two decades. The musicologist Ellen Rosand found that apart from “her somewhat older contemporary, Francesca Caccini, [Strozzi] is the only known woman of the period to have pursued a career as a composer and to have achieved some measure of public recognition.” In fact, she may been the most published composer within her genre in Venice.

“Che si può fare” is an aria for soprano and basso continuo from Strozzi’s final opus. The text is a lovelorn lament that can be paraphrased: “What can I do? The stars have no pity. If the gods won’t grant me peace, what can I do? / What can I say? / The heavens keep sending me disaster ... What can I say?”

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: March 21, 1685, in Eisenach, Germany

Died: July 28, 1750, in Leipzig

Work Composed: bf. 1721

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1931. Issay Dobrowen conducted with Anthony Linden and Mishel Piastro as soloists. Most recent—May 2012. Tim Day, Alexander Barantschik, and Robin Sutherland were the soloists.

Instrumentation: solo flute, solo violin, solo harpsichord, strings,

and continuo.

Duration: About 20 minutes

Between 1717 and 1723, Johann Sebastian Bach was Kapellmeister in Cöthen, where he wrote mostly secular music because Prince Leopold, as a Calvinist, eschewed elaborate liturgical works. He did, however, hire a topflight band for his own enjoyment—the players of the Kapelle were a tight-knit bunch who rehearsed in Bach’s apartment.

But in 1720, while mourning the death of his first wife, Maria Barbara, and frustrated by the Prince’s cuts to his music budget, Bach considered moving. He remembered the Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt, whom he had met in Berlin a few years earlier, and put together six concertos to send as an application portfolio, demonstrating an incredible range of instrumentations and styles. These Brandenburg concertos, as they have come to be called, were likely revisions of older pieces written at different times. In any case, nothing came of the application (Bach ultimately moved to Leipzig in 1723), and the manuscript was forgotten in a library until it was rediscovered in 1849. Even then, the concertos were not recognized as gems or widely performed until the 1930s.

The Fifth Brandenburg is an Italian-style concerto con molti strumenti in which several soloists (in this case, flute, violin, and harpsichord) weave around each other—a bit of a hybrid between the older concerto grosso and newer solo concerto. The keyboard part is particularly virtuosic, leading many scholars to conclude it was originally composed to show off a new harpsichord Bach purchased for the Cöthen court.

The Four Seasons, Opus 8, nos.1–4

Antonio Vivaldi

Born: March 4, 1678, in Venice

Died: July 27/28, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1718–23

SF Symphony Performances: First—April 1961. Enrique Jordá conducted with Frank Houser as soloist. Most recent—June 2017. Alexander Barantschik was leader and soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, strings, and continuo

Duration: About 35 minutes

Antonio Vivaldi wrote the four violin concertos comprising The Four Seasons (Le quattro stagioni) sometime before 1725, when they were published in Amsterdam as part of a larger set of 12 concertos called The Contest Between Harmony and Invention (Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione). Amsterdam was known for its high quality music publishers, and Vivaldi had released editions there since his L’estro armonico collection in 1711. A native of Venice, Vivaldi rarely traveled outside Italy, but thanks to his Dutch publishers’ newspaper ads and mail-order services (as well as an illicit trade in pirated manuscripts), his music was widely available across Europe and gained special popularity in German-speaking regions.

The Four Seasons was dedicated to Count Wenzel von Morzin, a Bohemian aristocrat whom Vivaldi served as “master of music in Italy” (an early example of remote work). Vivaldi was concurrently the director of secular music for the Governor of Mantua while also keeping his regular employment at the Ospedale della Pietà, a music school for orphaned girls and the illegitimate daughters of Venetian noblemen.

The concertos themselves were not brand new when published—they were probably first performed by Vivaldi himself in Mantua or Venice in the previous decade. So to create fresh and more elaborate versions for Count Morzin, Vivaldi added descriptive sonnets, which he is thought to have written himself. They appear both as a preface to the solo violin part and in excerpts scattered throughout the orchestral parts, showing the exact correspondence between the poetry and music. This was cutting edge at the time—rarely if ever before had instrumental music so vividly depicted real-life scenes. For instance, in Winter, you can hear the icy snow coming down in the orchestral introduction, and with the entry of the solo violin, the “harsh breath of a horrid wind.” Its iconic tutti refrain is foot-stamping in the snow (those left-right-left octaves), while the soloist’s quick double-stop passage in the upper register represents chattering teeth.

After centuries of irrelevancy, The Four Seasons regained popularity in the 1940s and then became almost ubiquitous on recordings and Saturday-morning classical radio. If over exposure has had a dulling effect, then they must be due again for reappraisal as the clever, innovative concertos they are.

Vivaldi’s Sonnets

Spring

[Allegro]

Springtime is upon us.

The birds celebrate her return with festive song,

and murmuring streams are

softly caressed by the breezes.

Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar,

casting their dark mantle over heaven,

Then they die away to silence,

and the birds take up their charming songs once more.

[Largo]

On the flower-strewn meadow, with leafy branches

rustling overhead, the goat-herd sleeps,

his faithful dog beside him.

[Allegro]

Led by the festive sound of rustic bagpipes,

nymphs and shepherds lightly dance

beneath the brilliant canopy of spring.

Summer

[Allegro non molto]

Under a hard Season, fired up by the sun

Languishes man, languishes the flock, and burns the pine;

We hear the cuckoo’s voice,

then sweet songs of the turtledove and finch.

Soft breezes stir the air, but threatening,

the North Wind sweeps them suddenly aside.

The shepherd trembles,

fearing violent storms and his fate.

[Adagio]

The fear of lightning and fierce thunder

Robs his tired limbs of rest

As gnats and flies buzz furiously around.

[Presto]

Alas, his fears were justified

The Heavens thunder and roar and with hail

Cut the head off the wheat and damage the grain.

Autumn

[Allegro]

The peasants celebrate, with songs and dances,

The pleasure of a bountiful harvest.

And fired up by Bacchus’s liquor,

many end their revelry in sleep.

[Adagio molto]

Everyone is made to forget their cares and to sing and dance

By the air which is tempered with pleasure,

And by the season that invites so many, many,

Out of their sweetest slumber to fine enjoyment.

[Allegro]

The hunters emerge at the new dawn,

And with horns and dogs and guns depart upon their hunting

The beast flees and they follow its trail;

Terrified and tired of the great noise

Of guns and dogs, the beast, wounded, threatens

Languidly to flee, but harried, dies.

Winter

[Allegro non molto]

To tremble from cold in the icy snow,

In the harsh breath of a horrid wind;

To run, stamping one’s feet every moment,

Our teeth chattering in the extreme cold,

[Largo]

Before the fire to pass peaceful,

Contented days while the rain outside pours down.

[Allegro]

We tread the icy path slowly and cautiously,

for fear of tripping and falling.

Then turn abruptly, slip, crash on the ground and,

rising, hasten on across the ice lest it cracks up.

We feel the chill north winds course through the home

despite the locked and bolted doors.

this is winter, which nonetheless

brings its own delights.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

San Francisco Symphony and has also written program notes for the Philadelphia Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, and Melbourne Symphony, among other organizations.

Portions of these notes were originally written for the St. Louis, Houston, and Melbourne symphonies.

About the Artists

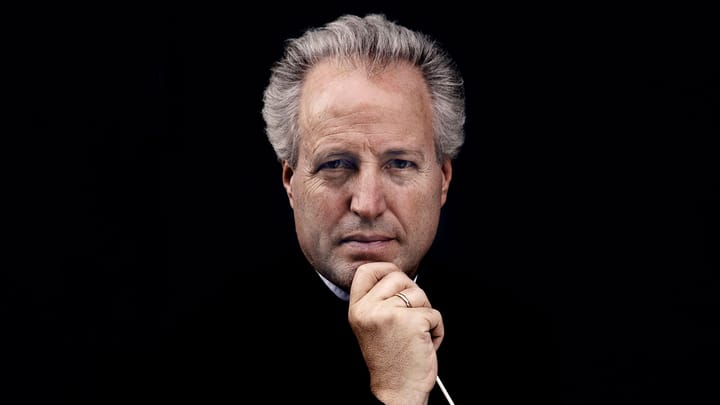

Alexi Kenney

Alexi Kenney is equally at home creating experimental programs, commissioning new works, soloing with orchestras, and collaborating with celebrated musicians. He is the recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant and a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award.

Kenney performs this season with the Pittsburgh Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Houston Symphony, Slovak Philharmonic, and Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana. Highlights of recent seasons include concertos with the Cleveland Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Detroit Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic, Indianapolis Symphony, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, Oregon Symphony, Louisville Orchestra, and l’Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne. He has been featured in a play-lead role with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and New Century Chamber Orchestra.

Born in Palo Alto, Kenney is an alumnus of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra, with whom he performed the Sibelius Violin Concerto in November 2016. He made his SF Symphony debut in July 2023 and will return to the Symphony next February to curate SoundBox.

Yubeen Kim

Yubeen Kim joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Flute in January 2024, and holds the Caroline H. Hume Chair. He was previously principal flute of the Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra and frequently played as guest principal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He won first prize at the 2022 ARD International Music Competition and the 2015 Prague Spring International Music Competition. He makes his SF Symphony solo debut with this program. Learn more about Yubeen Kim.

Jonathan Dimmock

Jonathan Dimmock has served the SF Symphony as a regular organist and harpsichordist since 2005, and recorded and toured with the Symphony. He is also principal organist at the Legion of Honor and an international recitalist. He previously served at three cathedrals: St. John the Divine in New York, St. Mark’s in Minneapolis, and Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. He cofounded American Bach Soloists in 1988.