In This Program

The Concert

Wednesday, June 4, 2025, at 7:30pm

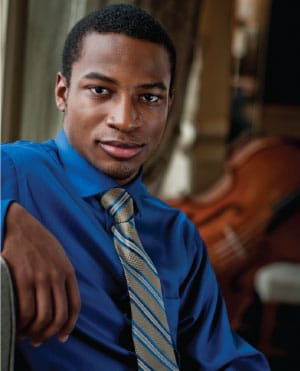

Xavier Foley double bass

Xavier Foley

Lost Child (2021)

Johann Sebastian Bach

Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 (bf. 1720s)

Prélude

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Gavottes I and II

Gigue

Xavier Foley

Letting Go (2020)

Ambiguity (2025)

Brown Chapel (2024)

Changes (2022)

Etude No. 3, Lament (2020)

Etude No. 10, The Dance (2020)

Etude No. 11, The Singer (2020)

Irish Fantasy (2016)

This concert is presented in partnership with

Program Notes

Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011

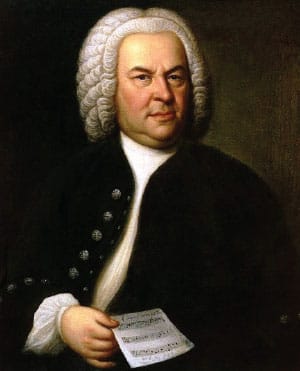

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: March 21, 1685, in Eisenach

Died: July 28, 1750, in Leipzig

Work Composed: bf. 1720s

We know little about the origins of Johann Sebastian Bach’s six suites for unaccompanied cello, which occupy a hallowed spot among cellists. And not just cellists; they are sometimes heard in transcriptions for viola or double bass (as here), and there has been a recent surge of violinists playing them, too, even though they have three each of unaccompanied sonatas and partitas that Bach wrote expressly for them.

Because the composer’s autograph score apparently has not survived, the early sources for these works are limited to four copies in other hands. The first of these seems to get us closest to Bach; it was written out in Leipzig by his second wife, Anna Magdalena, sometime in the span of about 1727–31, probably at the request of a former pupil of Bach’s who had moved away from Leipzig. Another is by Johann Peter Kellner, an organist-composer who was certainly a friend and possibly a pupil of Bach’s who copied out various of the master’s works. Comparisons of the four early sources yields many textural variants, even to the point of suggesting that Bach went on developing some of these pieces after completing them in a provisional state.

Although the surviving sources date from Bach’s time in Leipzig, where he moved in 1723, the general consensus is that at least portions were composed earlier, perhaps (at least in part) when he was working at the Weimar court (1708–17) or, more likely, when he was Kapellmeister to the music-loving Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen (1717–23). Bach produced many of his important instrumental pieces in Cöthen, among them (one supposes) his group of six sonatas and partitas for violin, which stand as a sibling set to the cello suites. Assigning the cello suites to that period invites the possibility that they were composed for either of two cellists who were among Bach’s colleagues there, Christian Ferdinand Abel or Christian Bernard Lienicke (or Lünecke).

Each of the suites follows a similar plan: a freely composed prelude followed by an allemande, a courante, a sarabande, a paired set of another dance movement (gavottes in the case of the Fifth Suite), and finally a gigue. The suites abound in polyphonic writing, often through multi-stopping or sustaining tones on two strings at once. All of the suites depend to an exceptional degree on the art of illusion, with the soloist relying on subtleties of rhythm, dynamics, and inflection to animate the independent lines that are suggested through the voicing of Bach’s highly deconstructed music.

In each of the suites, it is the prelude that displays the composer’s fantasy at its most exorbitant level. From their origins as short improvisations to ascertain that instruments were properly tuned and to set the key of an ensuing piece in the listener’s ear, preludes had grown by the 1720s into virtuosic inventions, often exploring the implications of small melodic cells and ranging through chromatic landscapes. In Suite No. 5, the Prelude begins in the depths, in duple time, and rises into a fugue in triple meter. The movements that follow them in these suites are all dances at heart. Except for the Sarabande, they are vivacious in their motion (energized by the prominent presence of dotted rhythms, a stylistically French touch) and forthright in their melodies, but they also display contrapuntal subtlety that one would scarcely anticipate from mere courtly dances. The Sarabande stands apart; here, almost everything is written in a single line, still implying counterpoint but with little actual double stopping, and it is the only movement of this suite that does not contain full chords. This yields a movement of lonely desolation that is exceptional even in this dark-hued suite.

Selected Works

Xavier Foley

Born: August 9, 1994, in Marietta, Georgia

Works Composed: 2016–25

Performance and composition intersect in Xavier Foley. Already, at age 30, he is a superstar in the world of the double bass and gaining recognition as a composer, with commissions from the Sphinx Organization, Carnegie Hall, and Atlanta Symphony.

A number of his works reference compositions by earlier composers. His Letter to Beethoven, which exists in versions for solo double bass and for double bass and piano, meditates on the scherzo from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. His Resurrection of Titan, a double concerto for violin and double bass, draws inspiration from the double bass solo in Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 and the orchestral bass part of his Symphony No. 2. “I like working with and draw[ing] inspiration from the motifs created by the composers who have influenced me,” says Foley. “The fact that their music has that much power—it’s worth learning from and it’s worth playing around with.”

In this recital, Foley plays some of his compositions featuring double bass. “Much of my music is quite challenging, given my interest in exploring the technical boundaries of the double bass,” he told journalist Noel Morris for a publication of Chicago’s Grant Park Music Festival. “Expanding the double bass repertoire and championing the double bass as a prominent solo instrument is a fundamental part of my artistic mission. Historically, there haven’t been many composers who also played the double bass as their primary instrument. . . .As a double bassist with a strong understanding of the technical aspects of the instrument, I’m able to compose music that shines a light on the limitless possibilities for it.”

He refuses to be pigeonholed by classifications of style. In an interview with Erik Petersons for the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, he stated: “I tend to think of musical genres as a branding function; certain sound bites are assigned a specific name. When I write something, my goal is to create diverse feelings that in the end create a musical story line. So I don’t necessarily lean toward a specific genre, but rather, I use musically branded material created in the past to help me create new combinations of sound.”

The pieces played here testify to the gravitational pull of many genres and styles. Of his blues-colored etude Lost Child, he says, “A lost child is a scary thing. The piece is not beautiful; it’s not sad. It’s kind of in the middle . . . anxious.” Letting Go employs the same sorts of harmonizations and fully realized chords Bach used in his Cello Suite No. 5, although Bach did not ask his interpreters to slap their instruments as Foley does. “Bach is one of my biggest influences,” Foley has observed, “especially in my counterpoint writing.”

Ambiguity—as the title suggests, you will have to decide. Brown Chapel is a jazz-inflected theme and variations that, he explains, is “dedicated to the talent of Brown Chapel AME Church of Ypsilanti, Michigan, that inspired me to become a musician as a child.”

Changes has a nostalgic streak without being actually sad, rather in a way that recalls Astor Piazzolla. His Etude No. 3, Lament, is a tender piece that Foley dedicated to his teacher Douglas Sommer, a member of the Atlanta Symphony who passed away in 2014. Of his Etude No. 10, The Dance, he remarks, unsurprisingly, “The goal of this etude is simple: make the listener dance!” Etude No. 11, The Singer, is a lyrical ballad; Foley describes it as “R&B in the classical style for double bass.”

His Irish Fantasy for Solo Double Bass is based on “The Clergy’s Lamentation” by Turlough O’Carolan (1670–1738), a blind Celtic harpist. Still in the repertoire of Irish fiddlers, pipers, and harpist-singers today, this irresistible melody came to Foley’s attention as the background music for the video game FATE, which he played when he was 11 years old.

—James M. Keller

Read a reminiscence from James M. Keller.

About the Artist

Xavier Foley

Xavier Foley is redefining what is possible on the double bass as a trailblazing soloist, composer, collaborative artist, and recipient of the Avery Fisher Career Grant. His compositions include Soul Bass, a concerto commissioned and premiered by the Atlanta Symphony under Jonathan Hayward, and For Justice and Peace, a genre-blending work for violin, double bass, and string orchestra, co-commissioned by Carnegie Hall, the Sphinx Organization, and New World Symphony. Other concertos include Galaxy Concertante for two double basses; Victory for double bass and string orchestra; and Resurrection of Titan for violin, double bass, and orchestra, commissioned by the Cabrillo Festival in association with Mahler Foundation. These works have been performed by ensembles across the United States including the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony, Sphinx Virtuosi, Kansas City Symphony, New West Symphony, Orchestra Lumos, Nashville Symphony, Oregon Symphony, Wisconsin Chamber Orchestra, and the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra.

Foley has captivated audiences with critically acclaimed recital appearances at major venues and festivals including the Kennedy Center, Kaufman Music Center, Shriver Hall, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Rockport Music, Morgan Library, National Gallery of Art, Harriman-Jewell Series, La Jolla Music Society, Marlboro Music Festival, Tippet Rise Art Center, Bridgehampton Festival, New Asia Chamber Music Society, South Mountain Concerts, and Wolf Trap.

Originally from Marietta, Georgia, Foley is a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, where he studied with Edgar Meyer and Hal Robinson. He won the 2016 Young Concert International Auditions, is an alumnus of the Perlman Music Program, and performs on a custom double bass made by Rumano Solano. He makes his debut at the San Francisco Symphony with this Recital.

Four Questions for Xavier Foley

What inspired you to pursue a career in classical music?

I started music because as a kid I had a hard time expressing my feelings through words. But I found that when I played the bass I could communicate something deep inside that I was never able to do with words.

And so that’s why I stuck with it.

Who has most inspired you as a musician?

As far as teachers that inspired me, number one is Edgar Meyer. Edgar was one of the first professional bass players I ever listened to. My first bass teacher, Doug Sommer, who was in the Atlanta Symphony, gave me an Edgar Meyer CD, and one of the pieces was called “The Great Green Sea Snake.” And I said to myself, that must be what professional bass sounds like. And that set the bar pretty high. Hal Robinson was another teacher who taught me not only how to be a great musician but how to be a better person. When I was at Curtis, I was put on probation my first year at 17 years old because I was misbehaving. But he set me straight, so thanks, Hal.

What’s your routine on concert days?

I like to sleep eight hours the night before a concert, so my mind is fresh. I try not to play too much and practice too much because I’ll get too tired—when I have the concert I’ll have mental fatigue, which is never good. So, maximum one hour; no more, maybe a little less.

What are some of your interests outside of music?

I run my own website, xavierfoley.com, because I like being able to combine business with music. There are a lot of ups and downs, but I take those opportunities to take accountability and learn from them.