In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, November 6, 2025, at 7:30pm

Friday, November 7, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, November 8, 2025, at 7:30pm

Inside Music Talk with Scott Foglesong, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

On stage at 6:30pm before each performance

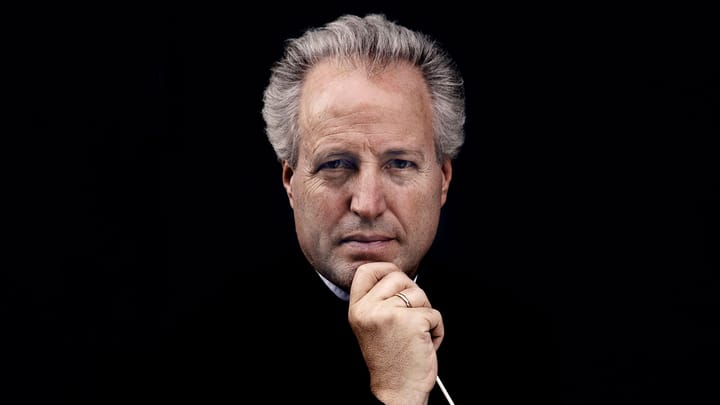

Karina Canellakis conducting

Antonín Dvořák

Scherzo capriccioso, Opus 66 (1883)

Sergei Prokofiev

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Opus 26 (1921)

Andante–Allegro

Theme (Andantino) with variations

Allegro ma non troppo

Alexandre Kantorow

Intermission

Jean Sibelius

Four Legends from the Kalevala, Opus 22 (1896)

Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island

The Swan of Tuonela

Lemminkäinen in Tuonela

Lemminkäinen’s Return

The November 7 concert is presented in partnership with

Alexandre Kantorow’s appearance is generously supported by the Shenson Young Artist Debut Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Rampell family.

These concerts are supported in part by the Mr. and Mrs. George J. Otto Sibelius Fund.

Inside Music Talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half is Jean Sibelius’s Four Legends from the Kalevala, based on the Finnish national epic, but fiercely original and personal in treatment of its folk material.

Scherzo capriccioso, Opus 66

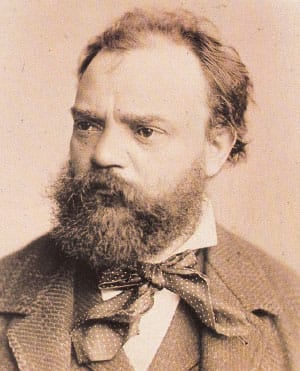

Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died: May 1, 1904, in Prague

Work Composed: 1883

SF Symphony Performances: First and only—April 1999. Jiří Bělohlávek conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 12 minutes

The title of Antonín Dvořák’s Scherzo capriccioso implies lightheartedness and jovial tone. While there are indeed elements of happiness, the “joke” seems somewhat more elusive. He wrote it in 1883, during a difficult time in his life. His mother had died the previous December, and he had lost three of his nine children a few years earlier. It was a time of darker musical output, including the Seventh Symphony and F-minor Piano Trio, as well as the Scherzo capriccioso.

Dvořák is famous for his travels to America and his desire to help develop an American musical voice in the Western art music idiom. But he spent his years before coming to America working to place his Bohemian musical language within Europe’s Austro-Germanic musical hegemony. He wrote to the German publisher Simrock asking him to publish his works with both German and Czech on the title pages. “I just wanted to tell you that an artist too has a fatherland in which he must also have a firm faith and which he must love,” he wrote to the publisher. The Scherzo capriccioso maintains Slavonic elements that were part of his musical culture and heritage while also attempting to adhere to what non-Czech concertgoers would have wanted to hear. This proved an effective strategy. The piece became one of his most popular works and was beloved throughout concert halls at the time.

The music displays multiple moods and a feeling of restlessness, even anxiety. The opening passage with its ascending fourth leap and repeated top note is more difficult than it might sound. Throughout the piece, there are several leaps and repeated notes that create a sort of arrested development of the melodic material. The music stutters at times, as if something is trying to get out but can’t quite express itself clearly enough. Later, there is an almost saccharine waltz. The piccolo buzzes around the top like a small mosquito trying ruin the fun. There are, however, moments of earnestness in the middle slow section. The English horn and clarinet trade a beautiful, tender melody. But then the orchestra takes off again with the waltz.

Just before the coda section, the horns call out as if over a distant lake. The orchestra reiterates the themes of the piece. A rolling harp cadenza leads to a solo horn call of the introductory material, a final reminder of the scherzo’s opening. Then the whole orchestra races through a rollicking coda toward the finish line. The piece ends on a thrilling note, full of energy and bravado. Yet in the coda, we are reminded that perhaps the “joke” was the stuttering awkwardness of the rhythmic motifs, repeated notes, and rhythmic instability. For all its seeming lightheartedness, there is depth at its core that invites further introspection.

Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Opus 26

Sergei Prokofiev

Born: April 23, 1891, in Sontsovka, Ukraine

Died: March 5, 1953, in Moscow

Work Composed: 1917–21

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1930. Alfred Hertz conducted with Sergei Prokofiev as soloist. Most recent—March 2018. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Behzod Abduraimov as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion (cymbals, castanets, tambourine, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 28 minutes

Sergei Prokofiev was raised at Sontsovka, an estate that his father managed in what is today Ukraine. His childhood wanted for nothing—in addition to his father teaching him the natural sciences and a general education, he had a French governess and two German governesses who taught him foreign languages. He also started taking formal music lessons at a young age, including two summers of theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano lessons from the composer Reinhold Glière when he was on summer break from the Moscow Conservatory in 1902 and 1903. Prokofiev’s privileged childhood gave him many opportunities, but it also perhaps made him less resilient in the face of criticism. This would challenge him deeply later in life.

When Prokofiev first traveled to the United States in August 1918, hoping to establish himself, he unknowingly arrived just before the Spanish influenza outbreak. His concert tour was delayed and his four-month-long tour ended up lasting nearly two years. When he did start performing, Prokofiev expressed frustration with the American public, criticizing them for not wanting to hear music that sounded too modernist for their more traditional tastes. Prokofiev felt he wasn’t valued and scoffed at the offers he was given for his work. “The American soul has the shape of a dollar,” he wrote, struggling at times to make ends meet in America.

Despite American audiences’ sometimes lukewarm reception of his music, Prokofiev found many ardent supporters in the United States, chief among them the Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who became conductor of the Boston Symphony in 1924. It was Koussevitzky who would become the champion of Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto and help launch it as the standard piece of repertoire that it is today. The German-born conductor Frederick Stock, of the Chicago Symphony, was introduced to Prokofiev’s music in 1918 and became yet another supporter. The composer would appear with the Chicago Symphony five times over the next several years, notably for the premiere of his Third Piano Concerto in December 1921.

Prokofiev took a break from the United States in February 1921 to spend spring and summer at a rental home on the Brittany coast. There he worked on an opera, The Fiery Angel (premiered posthumously), and completed his Third Piano Concerto. He returned to Chicago in October 1921 to prepare for two important December premieres: his opera The Love for Three Oranges with the Chicago Opera and his Third Piano Concerto (and his Classical Symphony) with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He was so focused on his opera that while attending a concert at Orchestra Hall on November 19 he realized he had not yet prepared the piano part for the first rehearsal on December 5. He was to perform the concerto with Stock conducting the first half. In the second half, Prokofiev would conduct his Classical Symphony. He set to work, diligently practicing the piano and preparing the score.

The premiere came on December 16, 1921. Although the composer admitted he made some mistakes in the second and third movements, he wrote in his diary that he “almost played for a five” (meaning an A+ grade). Even so, the audience was far more enamored of the symphony than the concerto and recalled Prokofiev to the stage seven times following the symphony’s finale. The reviews of the concerto then rolled in. The Chicago Tribune asserted that the concerto was “greatly a matter of slewed harmony, neither conventional enough to win affections nor modernist enough to be annoying.” Emil Raymond of Musical America wrote that it was “an attenuated piece of music, complex but paltry in effect and many opportunities for fine expression left hanging in the air.” He conceded that the piano part was a “colossal piece of work,” but he felt that there was a clear lack of longer melodic development. “No sooner has the composer realized that a singing, wholesome phrase has intruded into his scheme,” Raymond writes, then Prokofiev decides to “nullify it by contradictory and meaningless passages.”

The Music

Despite contemporary reviews, the concerto is today the most popular of Prokofiev’s five concertos, and for good reason. The music treads in the vicinities of modernism, neoclassicism, and more traditional music. It is not atonal, but it is also not adherent to 19th-century Romanticism, or even the Socialist Realism that would be expected from Prokofiev upon his return to the Soviet Union. The harmonic language is understandable, if not completely traditional. It is gestural and exciting, with freneticism and energy throughout.

The first movement opens with a clarinet solo, then is joined by the orchestra for a grand introduction. However, rather than continue this melodic line, the piano takes off, helter-skelter, and sets an energetic tone for the rest of the movement. There is a sardonic sense of humor in the first movement, with its flippant grace notes and ironic-sounding castanets.

The second movement is a theme and variations, with five variations and a coda. The orchestra opens with the theme, which is then taken by the piano for a colorful first variation. The second variation is more ferocious with polytonality in the brass. The third variation is a syncopated deconstruction of the theme. The slowest variation, the fourth, is marked freddo (cold) in the part, and is chilly, eerie, and distant sounding. The fifth variation rouses us from our chilled slumber toward the final coda.

The third movement opens with the bassoons, who introduce the swashbuckling piano music, a dialogue between the orchestra and piano. The two parties race toward the finish line, a thrilling climax that is full of kinetic energy and exuberance.

Prokofiev in San Francisco

In the spring of 1918, following the October Revolution, Prokofiev took the Pacific route from Russia to the United States and entered the country for the first time through San Francisco. To get here, he rode the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok in Russia’s Far East, made his way to Tokyo where he played a few recitals, and finally sailed to California by way of Honolulu. At the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay, he was detained by authorities who closely questioned whether he was a Bolshevik. Between 1910 and 1940, Angel Island mostly processed immigrants from Asia, but saw an influx of European visitors and refugees around the time of World War I and the Russian Revolution. Americans feared both German spies and communist infiltrators.

“Have you ever been in jail?” the officer asked Prokofiev, according to his diary. “Yeah … in yours,” he retorted. “Oh, so you’re a joker,” said the officer. After holding him for three days, the immigration agents were finally satisfied and ferried him ashore. “Now they were all smiles and offered cigarettes, but I found their ugly mugs so repellent that I went up on deck,” the composer wrote.

Nonetheless, Prokofiev appreciated the scenery. “As the mist began to dissipate, the beautiful outlines of the bay began to show themselves. From somewhere came the sound of a bell, not from a church but from foghorns. I did not, of course, expect this to be a place to look for picturesque landscapes, or castles, or legends.” Soon he departed for New York, and completed a nearly around-the-world trip by sailing to Paris in 1920.

Prokofiev returned to San Francisco a decade later, giving his only concert with the San Francisco Symphony on February 18, 1930, at the Exposition Auditorium (today Bill Graham, “an enormous hall seating 10,000, almost full”). He conducted selections from The Love for Three Oranges and played his Piano Concerto No. 3 (“better than I had done in LA”) with music director Alfred Hertz (“chuckling benevolently into his beard at passages he considers dissonant”). It was part of an all-Russian program alongside works by Glazunov and Rimsky-Korsakov.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Four Legends from the Kalevala, Opus 22

Jean Sibelius

Born: December 8, 1865, in Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus), Finland

Died: September 20, 1957, in Järvenpää, Finland

Work Composed: 1896

SF Symphony Performances: First complete—March 2002. Mikko Franck conducted. (The Swan of Tuonela was first performed in February 1914. Henry Hadley conducted.) Most recent—January 2019. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (both doubling piccolos), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbal, tambourine, snare drum, bass drum, and glockenspiel), harp, and strings

Duration: About 48 minutes

While studying at the Helsinki Music Institute, Jean Sibelius found himself in a social circle that included several pro-Finnish language activists. Finland had been under the control of Sweden and became a grand duchy ruled by Russia, but there was a growing movement that advocated for greater freedoms for the Finnish people. Sibelius spoke Swedish growing up and did not learn Finnish until his mother enrolled him at a Finnish-speaking school around 11 years of age. It was not until he moved to Vienna in 1890 that he turned his focus toward Finnish music and culture.

His relationship with his wife-to-be, the Finnish-language advocate Aino Järnefelt, helped open his eyes to the long and fascinating history of Finland. She would write letters to him in Finnish, and he would reply in Swedish “so that it does not take five minutes to write out each word,” he admitted. It was in their correspondence that he wrote about his fascination with the Kalevala, the national folk epic of Finland. The Kalevala and his involvement with the pro-Finnish cause changed the direction of his life. It also influenced his compositional style.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the Kalevala for Sibelius. The compilation of epic poems tells of beginning of the world through to the introduction of Christianity in Finland. The 50 runos (or cantos in English) were compiled by Elias Lönnrot in the early 19th century. He was a physician, polymath, philosopher, musician, philologist, botanist, and poet who took 11 trips to conduct fieldwork during his breaks as a district health officer. He met with Karelian and Finnish people to learn of their folklore and mythology, then published two versions, the second of which in 1849 became the canonical version. This work was pivotal in pushing for the recognition of the Finnish language and national identity, and has inspired countless musicians, from classical composers like Sibelius to contemporary folk musicians and folk-metal and prog-rock bands.

The Music

Sibelius’s Four Legends from the Kalevala follows the hero Lemminkäinen. It is alternatively known as the Lemminkäinen Suite, as the subject matter deals with runos from the two Lemminkäinen cycles. In 1893 Sibelius began work on an opera, Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat), but decided to abandon it. He took material from the prelude in 1896 for a new work, Tuonelan joutsen, (The Swan of Tuonela). This would form the most famous movement of the Four Legends, and is often performed as a standalone work. After the premiere of the Four Legends in 1896 with the Philharmonic Society under the composer’s baton, Sibelius withdrew the first two movements. He reworked the order and revised the movements as late as 1939, and they were not published until 1954, just a few years before Sibelius’s death.

The first movement, Lemminkäinen ja saaren neidot (Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island), follows the protagonist as he travels to an island of womenfolk who welcome him, but he is driven out by the men of the island. He returns home only to find it destroyed and everyone killed. Lemminkäinen mourns his mother but discovers she is still alive. She tells him soldiers from Pohjola were responsible and he vows to wage war on them.

The second movement, Tuonelan joutsen, (The Swan of Tuonela), depicts a swan swimming around Tuonela, the realm of the dead. There is not a direct connection to a runo, but the music is so achingly beautiful, with the mournful English horn solo over a string section divided into as many as 17 parts. The third movement, Lemminkäinen Tuonelassa (Lemminkäinen in Tuonela) connects to the second movement. Lemminkäinen is killed and his mother travels to Tuonela to bring him back to the realm of the living.

The fourth movement, Lemminkäinen palaa kotitienoille (Lemminkäinen’s Return) finds the title character deciding to sail back to Pohjola to seek revenge. However, Lemminkäinen is thwarted by the mistress of Pohjola who sends a frost over the water, freezing his boat and its occupants. The protagonist subdues Pakkanen, the Frost-fiend, with his power of persuasion (and his magical abilities), but he and his companion Tiera ruefully accept defeat and trudge back to their home in Kalevala by walking over the ice.

Not only does Sibelius take the several runos of the Kalevala for inspiration, but he also draws from the meter of the poetry (trochaic-tetrameter), and the melodies and rhythms the poets would have used for the music. He was inspired by the repetition and what Sibelius scholar James Hepokoski terms the “unyielding sameness” of the Kalevala poetry. The music from the Four Legends is melancholy, (intentionally) monotonous, and deeply personal to the composer.

—Alicia Mastromonaco

About the Artists

Karina Canellakis

Karina Canellakis has been chief conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic since 2019, leading the orchestra at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw and Utrecht’s TivoliVredenburg, and has been principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic since 2021. She was principal guest conductor of the Berlin Radio Symphony from 2019–23, and in 2023–24 was a featured artist in residence at Vienna’s Musikverein.

Highlights this season include her Lucerne Festival debut, Vienna Philharmonic debut at Mozart Week Salzburg, a seven- city European tour with the London Philharmonic and Anne-Sophie Mutter, and her Hamburg State Opera debut. She returns this season to the Chicago Symphony, Swedish Radio Symphony, and Vienna Symphony. Over recent seasons, she has developed close relationships with the Bavarian Radio Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, Vienna Symphony, and Munich Philharmonic, and is a repeat guest with the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, and Philadelphia Orchestra. She has toured Australia and made her debut in Japan in July 2025 with the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony and at the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut in October 2019.

April 2023 saw the start of a multi-album collaboration with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic and Pentatone, earning a Grammy nomination for Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra and Four Orchestral Pieces. Her second album for Pentatone, Bartók’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, was released in April 2025. She was also a featured artist for the launch of Apple Music Classical with a recording of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with Alice Sara Ott.

Already known to many in the classical music world as a violinist, Canellakis grew up in New York City, where she learned conducting and score-reading from her father, Martin Canellakis. She was then encouraged to become a conductor by Sir Simon Rattle while playing in the Berlin Philharmonic’s Orchestre-Akademie. She performed for several years as soloist, guest leader, and chamber musician, spending summers at the Marlboro Music Festival, until conducting eventually took over after she won the Sir Georg Solti Award in 2016.

Alexandre Kantorow

In 2019, aged 22, Alexandre Kantorow became the first French pianist to win the gold medal at the International Tchaikovsky Competition, along with the Grand Prix, granted only three times in the competition’s history. In 2024, he was recognized once again when he received the Gilmore Artist Award.

Highlights of Kantorow’s 2025–26 season include a Japanese tour with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, European tours with Filarmonica della Scala and the London Philharmonic, an Asian tour with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, and a US tour with the Philharmonia, including a performance at Carnegie Hall. He will also embark on a recital tour of North America and return to the Rotterdam Philharmonic and Bavarian Radio Symphony. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist with these concerts.

In recent seasons, Kantorow has performed with the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Berlin Philharmonic, Munich Philharmonic, and Budapest Festival Orchestra. In recital, he has appeared at Carnegie Hall, the Concertgebouw, Vienna Konzerthaus, Wigmore Hall, Philharmonie de Paris, Suntory Hall, and at festivals such as Edinburgh, Salzburg, La Roque d’Anthéron, Piano aux Jacobins, Verbier, Rheingau, and Klavierfest Ruhr. As a chamber musician, he performs regularly with Janine Jansen, Renaud Capuçon, Gautier Capuçon, and Matthias Goerne. With Liya Petrova and Aurélien Pascal, he is co-artistic director of the Rencontres Musicales de Nîmes and the Pianopolis festival in Angers.

Kantorow records exclusively for BIS. He was awarded the title of Chevalier of the National Order of Merit by the French president, having previously been made a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the minister of culture. In July 2024, Kantorow performed Ravel’s Jeux d’eau at the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympic Games.

Scott Foglesong is a Contributing Writer for the San Francisco Symphony and chair of music theory and musicianship at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. He also writes program notes for the California Symphony, Oregon Symphony, and Grand Teton Music Festival, among other organizations. He studied piano at the Peabody Conservatory and SFCM.