In This Program

The Concert

Friday, November 15, 2024, at 7:30pm

Saturday, November 16, 2024, at 7:30pm

Sunday, November 17, 2024, at 2:00pm

Kazuki Yamada conducting

Dai Fujikura

Entwine (2021)

US Premiere

Maurice Ravel

Piano Concerto in G major (1931)

Allegramente

Adagio assai

Presto

Hélène Grimaud

Intermission

Gabriel Fauré

Requiem, Opus 48 (1890)

Introit and Kyrie

Offertorium

Sanctus

Pie Jesu

Agnus Dei

Libera me

In Paradisum

Liv Redpath soprano

Michael Sumuel bass-baritone

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

Lead support is provided by the Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Guest Artists.

Kazuki Yamada’s appearance is generously supported by the Shenson Young Artist Debut Fund.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Entwine

Dai Fujikura

Born: April 27, 1977, in Osaka, Japan

Work Composed: 2021

US Premiere

Instrumentation: piccolo, flute (doubling 2nd piccolo), oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (2nd doubling contrabassoon), 2 horns, 2 trumpets, and strings

Duration: About 8 minutes

Dai Fujikura’s music is equally defined by its sonic precision and its sense of philosophical inquiry. Born in Japan, Fujikura moved to the United Kingdom at age 15 and studied with composers Daryl Runswick, Edwin Roxburgh, George Benjamin, and Peter Eötvös. He is now based in London with a diverse oeuvre that spans media, crosses genre lines, and sometimes features electronics, Japanese instruments, and European period instruments.

His unifying project is the creation of musical “utopias,” an approach which composer David Nunn, in a study of Fujikura’s work, described as a “fantastical, playful, and child-like striving for a world which is within the grasp of our sensory imagination but outside the realms of the phenomenal world.” Fujikura is the recipient of numerous awards including the 2005 Vienna International Composition Prize, 2007 Paul Hindemith Prize, and 2017 Silver Lion for Innovation in Music at the Venice Biennale. His works have been performed by the Tokyo Philharmonic, BBC Symphony, London Sinfonietta, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and International Contemporary Ensemble, among many others.

Notable recent performances include the 2020 premiere of his fourth piano concerto, Akiko’s Piano, which commemorates the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and the first staging of his opera A Dream of Armageddon at the New National Theatre Tokyo. Upcoming projects include a fourth opera, The Great Wave; a concerto for two orchestras; and a double concerto for flute and violin. Fujikura’s recordings are largely available through his own label, Minabel Records, and his scores are published by Ricordi Berlin.

The Music

Entwine, commissioned by the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, was premiered by the ensemble in June 2021. Speaking to the piece’s thematic grounding, Fujikura said:

I was asked to write a five-minute orchestral work expressing the current world situation . . . I began to see that the topic of this orchestral work should be about “touch”: the physical touch we can no longer take for granted, and how we can feel socially awkward now just by stepping out of the door and have to make sure we are standing far enough away from the other people in the street. I wanted to create an orchestral work where musical materials pass through from one instrument to another, like one “hand” to another: sharing, gathering, even ending up by being a crowd. Something we have all missed since the beginning of 2020, and something we now realize is what all humans need to live to the next day.

The piece is characterized by fluidly orchestrated gestures which pass, slide, and dovetail between the players and sections. Dense, potent utterances are overlaid with delicate resonances—a superstructure of tremolos, harmonics, and fluttering, muted brass which flickers in and out of earshot.

Driving moto perpetuo elements (among them the introduction of furiously animated pizzicati) push these elements towards their climax, a staggering chorale replete with groaning swells and crescendos. But after this final exhortation, the sound recedes into an ether of quietly twinkling harmonics.

—Lev Mamuya

Piano Concerto in G major

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1929–31

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1953. Massimo Freccia conducted with Nicole Henriot as soloist. Most recent—April 2019. Simone Young conducted with Louis Lortie as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, flute, piccolo, oboe, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, snare drum, bass drum, whip, and wood block), harp, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

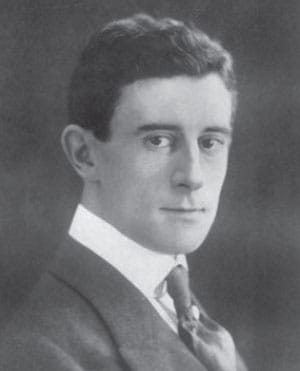

Between 1929 and 1932, Maurice Ravel worked on two piano concertos: the first in D major for left hand alone, commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, a pianist who had lost his right arm in the First World War. Next, Ravel completed the Piano Concerto in G major, which is arguably the lighter of the two pieces, despite being written for twice the number of fingers.

The outer movements are quick, zany, jazz-inspired. But they frame a slow movement of profound lyricism and radical simplicity: a middle that almost seems at odds with what comes before and after. The startling contrast is part of what gives this unique concerto its brilliance and wonder.

Jazz was popular in Paris in the 1920s. Just after the end of the war, Black American artists were welcomed into France’s cafés, concert halls, and nightclubs. Some performers, like Josephine Baker, moved permanently, finding freedom from segregation and less racial discrimination than in the United States. Meanwhile, writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway split their time between Paris and the Riviera, taking advantage of a favorable exchange rate and enjoying eccentric company.

Ravel, however, was not in the midst of the Jazz Age scene, having moved from Paris to the countryside commune of Montfort-l’Amaury in 1921, seeking peace and quiet in which to work. But in 1927 he found himself creatively blocked while trying to compose a violin sonata. Long past deadline and depressed, he took inspiration from the blues, which soothed his own “blues,” allowing him to complete the sonata. His knowledge of American music was still second-hand, but the following year, he embarked on a trip to the United States, his initial reluctance assuaged by $10,000 and a guaranteed supply of Gauloises Caporal cigarettes while underway. And so he crisscrossed the country from January through April of 1928, playing concerts and visiting everywhere from New York to the Grand Canyon. In March, he led the San Francisco Symphony in a concert of his own music.

Earlier that month, Ravel had celebrated his 53rd birthday in New York with a party attended by George Gershwin, a meeting dramatized in the 1945 film Rhapsody in Blue with the quip:

Gershwin: Monsieur Ravel, how much I’d like to study with you.

Ravel: If you study with me, you will only write second-rate Ravel instead of first-rate Gershwin.

But the influence also went the other way—Ravel treads close to the line in the outer movements of the Concerto in G, sometimes seeming to gloss on bits lifted from Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. He began writing the concerto back in Europe the year after his successful American tour, probably with the idea of making a return trip with it. But ultimately the 1932 premiere went to the French pianist Marguerite Long, with Ravel conducting the Orchestre Lamoureux in Paris. They toured Europe with the concerto to great acclaim, and in the end Ravel never returned to America.

The Music

The first movement starts at the crack of a whip with a mechanical, toy-like tune in the flute and piccolo. The piano’s grand entry (after “warming up” with arpeggios and glissandi) arrives with the sultry second theme. These two ideas make up much of the movement, recurring between jazzier episodes, lighthearted and exuberant.

The Adagio assai finds the piano unfurling an endless, lonesome melody against a constant waltz pulse in the left hand. The piano is alone for more than one quarter of the movement, before growing unease blooms into an orchestral texture. The middle is troubled, with ascending lines in the orchestra set sharply against descending patterns in the piano. This reaches a climax, and then the English horn enters with the original melody, while the piano decorates on a warm bed of strings. The soloist is taken back into the fold, now in company and no longer alone. The finale snaps back to the spirit of the first movement—it’s a brilliant romp, with misplaced accents and nimble athletics.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

A previous version of this note appeared in the program book of the St. Louis Symphony.

Requiem, Opus 48

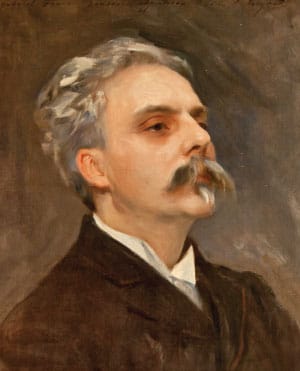

Gabriel Fauré

Born: May 12, 1845, in Pamiers, France

Died: November 4, 1924, in Paris

Work Composed: 1887–90

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1956. Enrique Jordá conducted with the San Francisco State College Choir and Saramae Endich and Heinz Blankenburg as soloists. Most recent—May 2014. Charles Dutoit conducted with the SF Symphony Chorus and Susanna Phillips and Hanno Müller-Brachmann as soloists. (Ragnar Bohlin most recently led the organ arrangement with the SF Symphony Chorus in May 2016.)

Instrumentation: solo soprano and baritone, chorus, 2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, harp, organ, and strings

Duration: About 40 minutes

La Madeleine is an imposing edifice in the shape of a colonnaded Greek temple, prominently situated in the eighth arrondissement of Paris. As with many Parisian churches, it boasts a magnificent organ and an impressive history of organist-composers who have directed the musical devotions within its gilded interior. In the latter third of the 19th century, when the eighth arrondissement became newly fashionable, La Madeleine assumed importance as the parish church for the well-to-do. Gabriel Fauré served as choirmaster beginning in 1877 and in 1896 was appointed organiste titulaire, a post he held for another nine years. It was at the funeral of a parishioner, the architect Joseph Lesoufaché, that Fauré’s enduring Requiem was first heard.

“My Requiem was composed for nothing . . . for fun, if I may be permitted to say so,” Fauré wrote. He did, however, have a reason for writing this work. He disliked the sacred music sanctioned for church use, which he considered banal and (in the case of operatic tunes fitted with religious texts) inappropriate. Fauré’s father had died on July 25, 1885, and the earliest sketches for movements of the Requiem appeared within the next two years, though Fauré never spoke of having written the work in memory of his father. By a quirk of fate, the composer’s mother died two weeks before the Requiem’s first performance, but there is no evidence that the Requiem was sung in her memory. We do, however, know that Fauré was affected deeply by the deaths of his parents.

Fauré’s father, director of a training school for teachers, provided his six children with a comfortable upbringing. Gabriel, the youngest, was the first in the family to demonstrate an inclination toward music. A family friend suggested that the boy be enrolled at a newly founded school to train organists and choirmasters. At age nine, Fauré and his father made the three-day journey to Paris. For the next 11 years, Fauré studied at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse, known as the École Niedermeyer after the founder and principal instructor, Louis Niedermeyer. The school’s training emphasized the singing and accompaniment of Gregorian chant and Renaissance music. These studies would exert a lasting influence on the young musician, and the modal harmonies and stylistic purity of chant and Renaissance polyphony would surface as expressive tendencies in Fauré’s later compositions.

Fauré’s discernment in musical matters extended to his work at La Madeleine. He was indifferent to the dogmatic tenets of orthodox Catholicism, and his religious music—especially the Requiem—reflects his convictions. He told a friend in 1902, “Perhaps instinctively I sought to break loose from convention. I’ve been accompanying burial services at the organ for so long now! I’ve had it up to here with all that. I wanted to do something else.” Fauré’s departure from convention in the Requiem is evident in the overall mood of the work. Most 19th-century settings of the Mass for the Dead are large-scale dramatic works that, by focusing on inherently theatrical aspects of the liturgical text, highlight the concept of divine judgment, the day of wrath when sinners will be separated from the holy and cast into eternal damnation. Fauré’s Requiem emphasizes human feeling, compassion, and tenderness: “People have said my Requiem did not express the terror of death; someone called it a ‘lullaby of death.’ But that’s the way I perceive death: as a happy release, an aspiration to the happiness of beyond rather than a grievous passage.”

One of the primary means by which Fauré accentuates human emotion in the Requiem is through his choice of texts—what he included and what he excluded, while still rendering the work liturgically functional for use at Catholic funeral services. Fauré chose to omit the Dies irae, the terrifying description of the Last Judgment, preferring instead to treat these apocalyptic sentiments with brevity and deftness in the relevant passages of the Offertorium and Libera me. At the center of the Requiem, following the Sanctus, Fauré places the tranquil Pie Jesu, the text of which is the final couplet of supplication from the Dies irae. Fauré scholar Carlo Caballero points out that, at La Madeleine and other Parisian churches, it was acceptable to substitute the Pie Jesu for the Benedictus, the movement that customarily follows the Sanctus. At the end of the traditional Requiem Mass text, Fauré appends two movements, the Libera me and the In Paradisum, both from the liturgy for burial. The Libera me is intended to be sung after the Mass has concluded, during the act of absolution; In Paradisum is sung outside the church, en route to the cemetery. By including both movements, Fauré has connected the funeral service and the burial into a single composition.

The Music

The dark-hued sonority of Fauré’s orchestration is evident in the first pages of the Introit and Kyrie, set in the somber key of D minor, as the chorus intones the initial words. The sound blooms on the phrase “et lux perpetua” (and perpetual light), highlighting the importance of this textual symbol in the Christian funerary tradition. The tenors unfurl a long melody, chant-like in its purity and simplicity, which will be reprised and sung by the full chorus for the concluding Kyrie statements. The Offertorium movement opens with imitative entries in the lower strings and later in the voices. The movement’s central section is a baritone solo intoned over a gently rocking accompaniment, and the movement’s close is an especially radiant “Amen.”

We hear the sound of violins for the first time in the Sanctus. The Hosanna section is a brief fortissimo passage allowing us a glimpse of the mounting excitement of Christ’s triumphant entry into Jerusalem. The music recedes quickly into the distance, as though Fauré did not wish to make too much of this vivid scene. The Pie Jesu, for solo soprano, is serene and contemplative as the supplicant prays that the departed may be granted rest, “sempiternam” (everlasting)—a word Fauré has borrowed from the end of the Agnus Dei text.

The Agnus Dei presents a gorgeous melody in the pastoral key of F major. When the tenors enter, we discover that the opening music is in fact a countermelody to the tenors’ arching phrases. The full chorus sings a more chromatic—and hence more anguished—setting of the Agnus Dei text before the tenors restore tranquility in C major. A magical modulation now occurs at the juncture where Fauré has elided the Agnus Dei and the Lux aeterna text: Sopranos sing “lux” (light) on the note C for two measures, a distant beacon; in their third measure on the word “aeterna” (eternal), the remainder of the chorus and orchestra enter with the warm sonority of A-flat major. The movement ends with a reprise of the somber Introit music in D minor (the text is the same as the start of the work), brightening in the final seven measures as the pastoral countermelody from the opening of the Agnus Dei comes back in D major, a balm of hope and reassurance.

The final two movements present a contrasting pair. The Libera me is dark and supplicating. The baritone solo seems urgent—and especially so when the full chorus takes up this music at the end of the movement. Horns and trumpets are added to underscore the abbreviated Dies irae portion of the Libera me. Altogether, the character of the Libera me is unique in this work, which otherwise is so consoling throughout. In Paradisum is a vision of Paradise. Sopranos sustain a long-breathed melody over 27 bars, while the tenors and basses enter with gentle commentary on the last phrase of the melody. The accompaniment is celestial, and the overall character is one of blissful calm. The work ends quietly as the chorus sings “requiem,” the word with which the piece began.

—Ronald Gallman

Fauré Requiem Text

lntroit and Kyrie

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine

et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Te decet hymnus, Deus in Sion,

et tibi reddetur votum in Jerusalem.

Exaudi orationem meam

ad te omnis caro veniet.

Kyrie, eleison.

Christe, eleison.

Kyrie, eleison.

Offertorium

O Domine, Jesu Christe, Rex Gloriae

libera animas defunctorum

de poenis inferni et de profundo lacu.

O Domine, Jesu Christe, Rex Gloriae

libera animas defunctorum de ore leonis,

ne absorbeat eus Tartarus ne cadant in obscurum.

Hostias et preces tibi Domine, laudis offerimus

tu suscipe pro animabus illis

quarum hodie memoriam facimus.

Fac eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam

Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini eus.

O Domine, Jesu Christe, Rex Gloriae

libera animas defunctorum

de poenis inferni et de profundo lacu,

ne cadant in obscurum.

Amen.

Sanctus

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth.

Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua.

Hosanna in excelsis.

Pie Jesu

Pie Jesu, Domine,

dona eis requiem.

Dona eis requiem, sempiternam requiem.

Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi,

dona eis requiem. Dona eis requiem,

sempiternam requiem.

Lux aeterna luceat eis, Domine,

Cum sanctis tuis in aeternum,

quia pius es.

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine,

et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Libera me

Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna

in die illa tremenda

Quando coeli movendi sunt et terra

Dum veneris judicare saeculum per ignem.

Tremens factus sum ego et timeo

dum discussio venerit atque ventura ira.

Dies illa dies irae,

calamitatis et miseriae

dies illa, dies magna

et amara valde.

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine

et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna

in die illa tremenda

Quando coeli movendi sunt et terra

Dum veneris judicare saeculum per ignem.

In Paradisum

In Paradisum deducant Angeli in tuo

adventu suscipiant te Martyres

et perducant te in civitatem sanctam Jerusalem.

Chorus Angelorum te suscipiat

et cum Lazaro quondam paupere

aeternam habeas requiem.

lntroit and Kyrie

Give them eternal rest, Lord,

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

A hymn befits you, God in Zion,

and a prayer will be rendered to you in Jerusalem.

Hear my invocation:

to you all flesh will come.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

Offertorium

Lord, Jesus Christ, King of glory,

free the souls of the dead

from hell’s punishments and the fathomless void.

Lord, Jesus Christ, King of glory,

free the souls of the dead from the lion’s jaw,

from the tormenting abyss, from the vertiginous darkness.

Sacrifices and supplications we offer in praise, Lord.

Receive these for those souls

whom we commemorate today.

Have them pass from death to life, Lord,

as you long ago promised to Abraham and his descendants.

Lord, Jesus Christ, King of glory,

free the souls of the dead

from hell’s punishments and the fathomless void,

from the vertiginous darkness.

Amen.

Sanctus

Holy, holy, holy Lord God of Hosts.

Heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

Pie Jesu

Holy Jesus, Lord,

give them rest.

Give them rest, eternal rest.

Agnus Dei

Lamb of God, who takes aways the sins of the world,

give them rest. Give them rest,

eternal rest.

May eternal light shine upon them, Lord,

with your saints eternally,

for you are holy.

Give them eternal rest, Lord,

and may perpetual light shine upon them.

Free me, Lord, from eternal death

on that dreadful day

when the heavens and earth are moved

as you come to judge the generations by fire.

I became shaken and afraid

as the accounting nears, and the wrath approaches.

That day is the day of wrath,

calamity and misery;

that day, that day is momentous

and exceedingly bitter.

Give them eternal rest, Lord,

and may perpetual light shine upon them.

Free me, Lord, from eternal death

on that dreadful day

when the heavens and earth are moved

as you come to judge the generations by fire.

In Paradisum

May angels bring you into Paradise.

May the martyrs receive you as you arrive

and guide you to the holy city of Jerusalem.

May a chorus of angles welcome you;

and with Lazarus, once a pauper,

may you have eternal rest.

Translation by Noam Cook

Supertitles: Ron Valentino

About the Artists

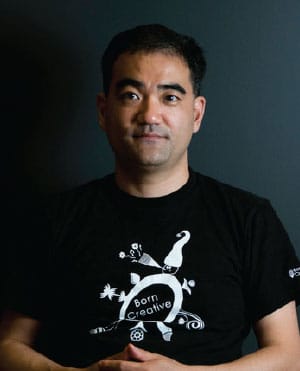

Kazuki Yamada

Kazuki Yamada is music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony and also artistic and music director of the Monte-Carlo Philharmonic. Last summer he returned to the BBC Proms with the CBSO, and this season appears with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin at Musikfest Berlin and will take the CBSO on tour to Europe and Japan. With Monte-Carlo Opera, he leads a double bill of Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges and L’heure espagnole, and debuts with the Berlin Philharmonic, Filarmonica della Scala, Swedish Radio Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and the San Francisco Symphony with these performances.

Born in Kanagawa, Japan, Yamada worked closely with Seiji Ozawa, which served to underline the importance of what he calls his “Japanese feeling” for classical music. He continues to work and perform in Japan every season with the NHK Symphony and Yomiuri Nippon Symphony. He studied music at Tokyo University of the Arts and won first prize in the 51st International Besançon Competition for Young Conductors in 2009. He now resides in Berlin.

Hélène Grimaud

Hélène Grimaud is not just a deeply passionate and committed musical artist, but also a wildlife conservationist, a human rights activist, and a writer. She has been an exclusive Deutsche Grammophon artist since 2002. Her recordings have been awarded numerous accolades, including the Cannes Classical Recording of the Year, Choc du Monde de la musique, Diapason d’or, Grand Prix du disque, Record Academy Prize (Tokyo), Midem Classic Award, and Echo Klassik Award. Her contributions have been recognized by the French government, which admitted her to the Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur at the rank of Chevalier.

Recent projects include a focus on Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov as well as on the connection between Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms. Concert highlights include appearances with the London Philharmonic, Luxembourg Philharmonic as part of a residency at the Luxembourg Philharmonie, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and Camerata Salzburg.

Grimaud was born in Aix-en-Provence, was accepted into the Paris Conservatoire at 13, and won first prize in piano performance three years later. She continued to study with György Sándor and Leon Fleisher until she gave her debut recital in Tokyo in 1987. That same year, Daniel Barenboim invited her to perform with the Orchestre de Paris. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist in February 1993.

Liv Redpath

Liv Redpath appears this season with Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia as Agnès in Written on Skin, Santa Fe Opera as Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, Bavarian State Opera as Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, and La Monnaie as the Woodbird in Siegfried. She makes her San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Last season, she made multiple debuts including the Royal Opera House in the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor, the Metropolitan Opera as Oscar in Un Ballo in Maschera, Berlin Philharmonic in Schoenberg’s Die Jakobsleiter, Hamburg State Opera for Lucia, the English Concert as Drusilla in L’incoronazione di Poppea, and the Atlanta Opera as Tytania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. She also returned to the Metropolitan Opera to sing Pamina in The Magic Flute and Santa Fe Opera for performances as Zerlina in Don Giovanni and Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier.

Redpath was a finalist at the 2019 Operalia Competition and received second prize, the special French opera prize, and audience favorite at the 56th Tenor Viñas International Contest. A graduate of Harvard University and the Juilliard School, she was a Domingo-Colburn-Stein Young Artist with the Los Angeles Opera.

Michael Sumuel

Michael Sumuel appears this season with the Metropolitan Opera in the title role of Le nozze di Figaro, Washington National Opera as Porgy in Porgy and Bess, and the Canadian Opera Company and LA Opera as Sharpless in Madama Butterfly. He makes debuts with the Chicago Symphony, Camerata Salzburg, and Houston Symphony.

Operatic highlights include the Metropolitan Opera as Reginald in X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X and Belcore in L’elisir d’amore; San Francisco Opera for the title role in Le nozze di Figaro, Escamillo in Carmen, and Elviro in Xerxes; Lyric Opera of Chicago as Masetto in Don Giovanni; Glyndebourne Festival Opera as Sharpless, Junius in The Rape of Lucretia, and Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Seattle Opera as the title role in Figaro and Leporello in Don Giovanni; and Santa Fe Opera in Carmen. In concert, he has appeared with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony, and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Sumuel was awarded a Richard Tucker Career Grant, was a Metropolitan Opera National Council Audition grand finalist, and won the Dallas Opera Guild Vocal Competition. He is an alumnus of the Houston Grand Opera Studio, Merola Opera Program, and the Filene Young Artist program at Wolf Trap Opera. He currently resides in San Francisco with his wife and son and made his San Francisco Symphony debut in December 2012.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

Under Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance. She has also prepared choruses for the Chicago Symphony, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, and Music Academy of the West.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

SOPRANOS

Elaine Abigail

Adeliz Araiza

Naheed Attari

Sylvia V. Baba

Alexis Wong Baird

Morgan Balfour*

Arlene Boyd

Olivia T. Brown

Laura Canavan

Rebecca Capriulo

Phoebe Chee*

Lauren Diez

Elizabeth Emigh

Cara Gabrielson*

Tiffany Gao

Ashley Hecht

Hyun Suk Jang

Betsy Johnsmiller

Anna Keyta*

Ellen Leslie*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Nancy Munn*

Natalia Salemmo*

Rebecca Shipan

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Lauren Wilbanks

ALTOS

Carolyn Alexander

Terry A. Alvord*

Celeste Camarena

Enrica Casucci

Carol Copperud

Marina Davis*

Corty Fengler

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen Josaitis

Gretchen Klein

Donna Kulkarni

Katherine M. Lilly

Joyce Lin-Conrad

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Leandra Ramm*

Linda J. Randall

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Sandy Sellin

Dr. Meghan Spyker*

Kyle S. Tingzon*

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

Hannah J. Wolf

TENORS

Paul Angelo

Carl A. Boe

Alexander P. Bonner

Seth Brenzel*

Daniel J. Costa

Scott Dickerman

Christian Emigh

Elliott JG Encarnación*

Sam Faustine*

Patrick Fu

Ron Gallman

Kevin Gibbs*

Edward Im

Alec Jeong

Benjamin Liupaogo*

Joachim Luis*

Monty M. Maisano

Justin Farrell Marsh

Jack O’Reilly

Darita Seth*

Tetsuya Taura

John A. Vlahides

David von Bargen

Jack Wilkins*

Weichen Winston Yin

John Paul Young

Jakob Zwiener

BASSES

Simon Barrad*

Sean Brooks

Phil Buonadonna

Robert Calvert

Joseph Calzada*

Sean Casey

Adam Cole*

Noam Cook

James Radcliffe Cowing III

Malcolm Gaines

Rick Galbreath

Richard M. Glendening

Bradley A. Irving

Roderick Lowe

Clayton Moser*

Case Nafziger

Julian Nesbitt

Bradley C. Parese

Jess Green Perry

Mark E. Rubin

Chung-Wai Soong*

Storm K. Staley

Michael Taylor*

Connor Tench

David Varnum*

Nick Volkert*

Goangshiuan Shawn Ying

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist