In This Program

The Concert

Tuesday, November 4, 2025, at 7:30pm

Itzhak Perlman violin

Rohan De Silva piano

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Violin Sonata in G major, K.301 (1778)

Allegro con spirito

Allegro

César Franck

Violin Sonata in A major (1886)

Allegretto ben moderato

Allegro

Recitativo–fantasia

Allegretto poco mosso

Intermission

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Sonatina in G major, Opus 100 (1893)

Allegro risoluto

Larghetto

Molto vivace

Finale: Allegro

Additional works to be announced from the stage.

Presenting Sponsor of The Great Performers Series

Program Notes

Violin Sonata in G major, K.301

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1778

A title page announcing “Sonatas for the keyboard, which may be played with violin accompaniment” might sound ominous to a modern violinist, ever alert to the danger of being drowned out by an inconsiderate pianist. But this original title has something to tell us about our present-day expectations versus the state of affairs in Mozart’s day. For a modern concertgoer, the term “violin sonata” conjures up an image of violinist and pianist on stage, equal partners performing a hefty and often technically demanding concert work. We think Beethoven, we think Brahms, we think Franck and Prokofiev and Fauré and Debussy. But the 18th-century violin sonata evokes a different vision. The setting morphs from concert hall to living room, the pianist gets most of the best stuff, and both length and demeanor are relatively modest, as befits music for an intimate venue with only a few listeners, or none. Pianos weren’t all that hefty back then, nor did they sustain tones particularly well. String instruments were typically cast in the role of making up for that deficiency, rather than as soloists in their own right.

Thus that aforementioned title page, attached to a set of four sonatas engraved in Paris in 1764 and dedicated to Queen Marie Antoinette by eight-year-old Mozart. In those oh-so-early sonatas Mozart wrote for the genre as it then existed, but it wasn’t all that long before he sought a growing independence for the violin, and with it, a reconfiguration of the violin sonata into a bonafide duo in which neither instrument calls the shots. He would fully realize that ambition after his move to Vienna in 1781, but well before then he produced a number of sonatas that stand as milestones towards that eventual goal.

In 1778, Mozart, accompanied by his mother, embarked on a tour to Mannheim and Paris. The visit to the French capital was woefully unsuccessful for the 22-year-old musician. The French had all but forgotten the erstwhile child prodigy and displayed little interest in the now gawky young adult. His Paris Symphony got a performance but to no particular notice. He wrote a concerto for flute and harp, but wasn’t paid for it. Tragedy then struck when his mother took ill suddenly and died on July 3.

Dismal though the tour was, it had started out well enough in Mannheim, in those days the home of a justly famous orchestra and the breeding ground of the newest music. Wolfgang composed five violin sonatas in Mannheim and published them soon after in Paris as his Opus 1, blithely disregarding that he already had three hundred works to his credit. Those sonatas, which substantially improve parity between violin and piano, are sometimes grouped together as the Palatine Sonatas, given their dedication to Countess Palatine Elisabeth Auguste of Sulzbach, although their more common moniker is the Mannheim Sonatas, K.301–306.

From its first paragraph, the G-major sonata, K.301, demonstrates the genre’s progress, as the violin presents the primary theme with a simple accompaniment in the piano. Those roles are exchanged upon repetition, and throughout the movement the two instruments perform collaboratively—they swap responsibilities, engage in follow-the-leader badinage, and even deftly fill in missing notes from the other’s harmonies.

The chipper and gracious second movement sustains that commitment to shared authority. It’s cast in classic rondo form in which a central reprise is cyclically repeated, interleaved with contrasting episodes. Rondos can be prone to tedium as those repetitions of the reprise pile up, each more predictable than the last. Given this sonata’s overall informality, Mozart doesn’t seem particularly concerned about such potential shortcomings. Nevertheless, he provides sufficient tedium-busting variety via unexpected key changes and refreshing embellishments.

Violin Sonata in A major

César Franck

Born: December 10, 1822, in Liège

Died: November 8, 1890, in Paris

Work Composed: 1886

César Franck’s compositional output up through midlife offers only hints of the treasures to come. It’s mostly starchy liturgical organ and vocal music, appropriate fodder from a solidly respectable organist and church musician. The fireworks started happening only during Franck’s final decade, thanks to a golden-years creative outburst.

It’s a wonder that Franck had a late bloom at all. Whatever fires burned within had been dampened to near-extinction by a succession of overbearing family members, starting with his father, Nicolas-Joseph, who combined bristling rectitude with unbending ambition for his progeny. Little César did passably well with piano and composition study at the Paris Conservatory, but brilliance wasn’t in the cards. That led to his being trundled back to Belgium by a disgruntled father who had reluctantly acknowledged that his son would not be illuminating Europe with scintillating keyboard pyrotechnics. So César—sweet, gentle, browbeaten—pursued a quiet career as an organist and teacher. Eventually he fell in love and sought marriage. Mont Père duly erupted in fulminating disapproval, but to no avail. Manifesting hitherto unsuspected spine, César stood up to his intimidating father and married Eugénie-Félicité-Caroline Saillot.

He had jumped from the frying pan into the fire. Madame Franck was even more dictatorial than her father-in-law, although her persona ran more towards softly persistent goad than barking drill sergeant. She preferred a husband swaddled in bourgeois stuffiness, and she got her way until César’s 1872 ascension to the professorship of organ at the Paris Conservatory. His circle of spectacularly gifted students, including d’Indy, Chausson, Duparc, and Vierne, fertilized the sprouting of long-germinating musical ideas. Franck’s newfound musical potency and free-form teaching caused consternation among his colleagues, who viewed him as a heretic who subverted established Conservatory methods and materials. But their concern was nothing against Mme Franck’s fury. She detested the newly-arisen sensuality in her husband’s music and blamed his students for having shepherded her trusting sheep of a husband astray.

An attractive if unproven notion persists of a golden-years yen for a young Irishwoman. If true, maybe it lit him up a bit. Whatever the cause, Franck’s late works combine technical rectitude with a well-nigh lubricious harmonic and melodic imagination. They are his legacy to posterity: the Piano Quintet and String Quartet, the symphonic poems Le Chasseur maudit and Les Djinns, the Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue for piano, the Symphonic Variations, the revered Symphony in D minor, and the Sonata in A major of 1886, one of the great pillars of the Romantic violin sonata repertory.

The sonata began its long and happy life as Franck’s wedding present to the luminous Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe. The official premiere, by Ysaÿe and pianist Marie-Léontine Bordes-Pène at the Brussels Museum of Modern Painting, went beautifully but could have been a disaster due to a slight miscalculation on the part of the concert promoters. The directors of the museum prohibited any artificial lighting in rooms that contained paintings, a sensible precaution considering the greasy film deposited everywhere by the gaslights of the day. That mandated a reasonably early starting time so as to take advantage of the available daylight. But they began at 3:00 in the afternoon, it was a long program, the Franck was at the end, and night was rapidly approaching. Ysäye and Bordes-Pène began their performance in atmospheric dimness, and by the second movement they were playing in the dark. But they chose to soldier on, as did the audience. Both players had the work by memory, and in the absence of distracting vision the music came all the more alive. Franck’s student Vincent d’Indy marveled that “music, wondrous and alone, held sovereign sway in the darkness of night.”

Like much of Franck’s later work, the Sonata is cyclic, meaning that it employs a brief musical idea that threads through all of the four movements, morphing and evolving as it goes. Whether encountered as Berlioz’s idée fixe or Tchaikovsky’s “motto” theme, a cyclic motive acts as a unifying agent that imparts structural unity to multi-movement works. Franck’s A-major sonata provides a particularly felicitous use of cyclic structure, its motivic unity permeating the work from first to last. The cyclic theme is the first thing we hear in the first movement, its characteristic chain-of-thirds persisting throughout in one guise or another, whether in the virtuosic Allegro second movement, the improvisatory Recitativo-fantasia, or in the valedictory Allegretto poco mosso with its lyrical yet Apollonian reserve that eventually heats up to a downright Dionysian exultation for the conclusion.

Violin Sonatina in G major, Opus 100

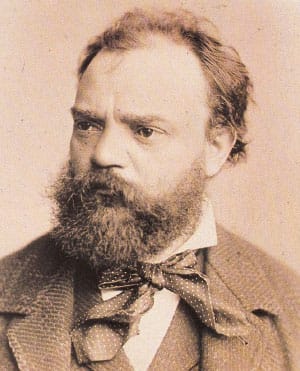

Antonín Dvořák

Born: September 8, 1841, in Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died: May 1, 1904, in Prague

Work Composed: 1893

Nineteenth-century America was more backwoods than desert when it came to classical music. To its credit, the country boasted fine conservatories, elegant concert halls, choruses hither and yon, and a steady supply of renowned touring artists. But that was about it. American concert music was largely imported rather than domestic, while a pervasive anti-Americanism in the arts motivated promising young native talent to decamp for Europe. A smattering of homegrown American composers contented themselves with churning out reams of faux Mendelssohn, echt Schumann, and ersatz Brahms, perhaps with a dollop of superficially understood American idioms for local color.

New York arts patron Jeannette Meyers Thurber, determined to initiate a cultural reset, sought to create a government-funded conservatory that could aid in fostering American concert music. The National Conservatory of Music of America opened in 1885. The institution’s goals were lofty and progressive, given its mission to include female, disabled, and minority students. Too lofty, as it turned out: federal funding never materialized and philanthropy proved insufficient. The National Conservatory was on life support by the 1920s and effectively defunct once the Great Depression kicked in, but during its brief shining moment it made substantial contributions to American music.

Thurber recognized the need for a musician of international stature to head up the Conservatory. She was successful in convincing Antonín Dvořák to take up the directorship in 1892. Unlike some Europeans, such as Charles Dickens, who took a dim view of all things American, Dvořák was happy in the United States, particularly when he discovered the tiny town of Spillville, Iowa, with its substantial Czech-speaking population. He stayed at the Conservatory until 1895.

The Sonatina in G major, Opus 100, was Dvořák’s last chamber work written during his American period. He told his publisher Fritz Simrock that he intended the sonatina “for youths (dedicated to my two children),” but quickly added that “even grown-ups, adults, should be able to converse with it.”

Despite its small scale, or maybe because of it, the sonatina encapsulates and concentrates many of the virtues that render Dvořák’s music so attractive to listeners and performers alike. Like his mentor Johannes Brahms, Dvořák mostly spoke in a late-Romantic language that was stripped of Wagnerian complexities, while he steadfastly maintained traditional Classical structures such as sonata form and rondo. Dvořák typically injected his compositions with healthy doses of folk elements, including African American and Native American idioms in his American works.

The sonatina follows the Classical layout of four movements. The Allegro risoluto opening movement strides along confidently in a sunny mood throughout, even considering a minor-mode contrasting theme that emits a goodly whiff of the pentatonic (five-tone) mode, a characteristic element of Dvořák’s ‘American’ nativist style.

Dvořák is said to have notated the folk-like theme of the second Larghetto movement on his shirt sleeve while on a visit to Minnehaha Falls in Minnesota. More introspective than mournful, the Larghetto is enlivened by a shimmering faster central section that refers back to the themes of the first movement. For his third movement, Dvořák conjures up a sturdy, peasant-like scherzo that also channels the first movement’s melodic materials while injecting healthy doses of irresistible good cheer.

The Allegro finale brims over with energy, robust dance rhythms, abundant syncopations, and a delightfully skittish secondary theme. A pensive central interlude evokes the introspection of the second movement while referencing the first movement’s themes, then the opening energy re-asserts itself and the sonatina gallops merrily along to its bright, sparkling conclusion.

—Scott Foglesong

About the Artists

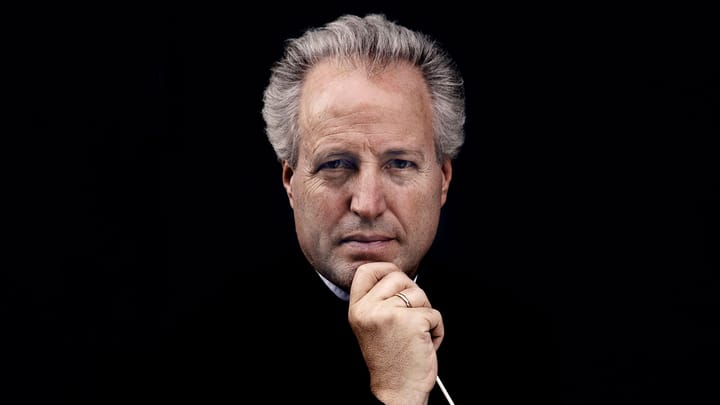

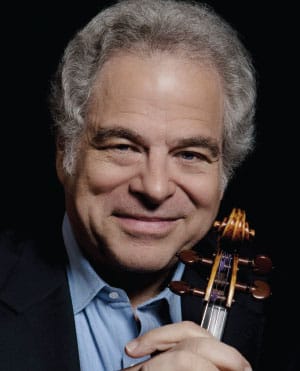

Itzhak Perlman

Undeniably the reigning virtuoso of the violin, Itzhak Perlman enjoys superstar status rarely afforded a classical musician. Beloved for his charm and humanity as well as his talent, he is treasured by audiences throughout the world who respond not only to his remarkable artistry but also to his irrepressible joy for making music.

Having performed with every major orchestra and at concert halls around the globe, Perlman was granted a Presidential Medal of Freedom—the nation’s highest civilian honor—by President Obama in 2015, a National Medal of Arts by President Clinton in 2000, and a Medal of Liberty by President Reagan in 1986. Perlman has been honored with 16 Grammy Awards, four Emmy Awards, a Kennedy Center Honor, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and a Genesis Prize. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in February 1969 at the War Memorial Opera House, made his Davies Symphony Hall debut in 1982, and returns next March to lead a special program with the Orchestra.

In the 2025–26 season, Perlman celebrates his 80th birthday season with a variety of programs. He brings his iconic PBS special In the Fiddler’s House program to New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Dallas, Santa Barbara, and Davis in celebration of the program’s 30th anniversary, alongside today’s klezmer stars. His orchestral engagements include Cinema Serenade programs with the Cleveland Orchestra, Louisville Orchestra, and Colorado Springs Philharmonic. He also makes a special appearance with the Colorado Symphony at Carnegie Hall. He continues touring An Evening with Itzhak Perlman, which captures highlights of his career through narrative and multimedia elements intertwined with performance, and plays recitals across the United States with longtime collaborator Rohan De Silva.

For more than 30 years, Perlman has been devoted to music education, mentoring gifted young string players alongside his wife, Toby, in the Perlman Music Program. He has taught at the program each summer since its founding in 1994. With close to 800 alumni, PMP is shaping the future landscape of classical music worldwide. Perlman holds the Dorothy Richard Starling Foundation Chair at the Juilliard School and has an exclusive series of classes with Masterclass.com as the company’s first classical-music presenter.

Rohan De Silva

Rohan De Silva has partnered with Itzhak Perlman in recitals worldwide and performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, the Library of Congress, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, the Barbican, Wigmore Hall, Bronfman Auditorium, Suntory Hall, and multiple times at the White House. A native of Sri Lanka, De Silva was invited in 2015 by the prime minister of his country to perform for US Secretary of State John Kerry during his historic visit to Sri Lanka. This season, De Silva tours alongside Itzhak Perlman with recitals across North America, and also collaborates on the multimedia program An Evening with Itzhak Perlman. He made his debut at the San Francisco Symphony in February 1993.

De Silva studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where he received the Grover Bennett Scholarship, the Christian Carpenter Prize, the Martin Music Scholarship, the Harold Craxton Award, and the Chappell Gold Medal for best overall performance. He was the first recipient of a special scholarship in the arts from the President’s Fund of Sri Lanka, which enabled him to enter the Juilliard School. He was awarded Best Accompanist at the Ninth International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow and received the Samuel Sanders Collaborative Artist Award presented to him by Itzhak Perlman at Carnegie Hall. In 2015, he was appointed Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music in London. De Silva has recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, Sony Classical, Collins Classics, RCA Victor, and Chandos. He served on faculty at the Perlman Music Program from 2000–07 and currently teaches at both the Juilliard School and the Heifetz International Music Institute.