In This Program

The Concert

Friday, May 23, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, May 24, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, May 25, 2025, at 2:00pm

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

Magnus Lindberg

Chorale (2002)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Alban Berg

Violin Concerto (1935)

Andante–Allegretto

Allegro–Adagio

Isabelle Faust

Intermission

Igor Stravinsky

The Firebird (1910)

Introduction

Scene I

Kashchei’s Enchanted Garden—

Appearance of the Firebird pursued by Ivan Tsarevich—

Dance of the Firebird—

Ivan Tsarevich Captures the Firebird—

Supplication of the Firebird—

Appearance of the Thirteen Enchanted Princesses—

Game of the Princesses with the Golden Apples (Scherzo)—

Sudden Appearance of Ivan Tsarevich—

Khorovod of the Princesses—

Daybreak—

Magic Carillon; Appearance of Kashchei’s Guardian Monsters;

Capture of Ivan Tsarevich—

Arrival of Kashchei the Immortal; His Dialogue with Ivan Tsarevich;

Intercession of the Princesses—

Appearance of the Firebird—

Dance of Kashchei’s Retinue Under the Firebird’s Spell—

Infernal Dance of all Kashchei’s Subjects—

Lullaby (Firebird)—Kashchei’s Death

Scene II

Disappearance of the Palace and Dissolution of Kashchei’s Enchantments; Animation of the Petrified Warriors;

General Thanksgiving

These concerts, a part of The Barbro and Bernard Osher Masterworks Series, are made possible by a generous gift from Barbro and Bernard Osher.

Program Notes

At a Glance

On the second half is the complete ballet music from Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird, his first success that brought him international fame. The story tells how Prince Ivan Tsarevich—with the help of the mythical Firebird—faced Kashchei, a monstrous king protected by a magic egg. Stravinsky’s magnificent score was deeply rooted in Russian folk song and opera, but also discovered new colors and rhythms that would influence orchestral music forever after.

Chorale

Magnus Lindberg

Born: June 27, 1958, in Helsinki

Work Composed: 2002

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets,

2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, and strings

Duration: About 6 minutes

Magnus Lindberg emerged on the international music scene in the 1980s, one of a generation of groundbreaking Finnish composers that included Kaija Saariaho, Jouni Kaipainen, and Esa-Pekka Salonen (his friend and junior by three days). All four were products of the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, where they studied with Paavo Heininen, a renowned developer of talent. Both Lindberg and Salonen also worked with another senior eminence of Finnish music, the composer Einojuhani Rautavaara.

Lindberg’s early style revealed a penchant for complexity, and during the 1980s he became preoccupied with intricate rhythmic interactions on multiple levels. In 1983, his Zona for solo cello and chamber ensemble brought his exploration of rhythmic intricacy to the practical limit of the unaided human mind. For his next major work, the award-winning Kraft, he devised a computer program to assist in generating even more meticulous calculations to fuel his composition.

After the intense difficulty of Zona and Kraft, Lindberg proceeded to works that, in many cases, seem less insistent on overload. Even in the modern “classicist” mode, many of Lindberg’s scores nonetheless remain generally vigorous, colorful, dense, and kinetic, and despite the extreme refinement of his compositional method, his scores manage to sound spontaneous. His work has been honored with the UNESCO International Rostrum for Composers, the Prix Italia, the Nordic Council Music Prize, the Royal Philharmonic Society Prize, and the Wihuri Sibelius Prize.

In recent years he has carved out a particular reputation as a composer of orchestral music. “The orchestra is my favorite instrument,” he has remarked. This has both led to stints as composer-in-residence for such orchestras as the New York Philharmonic, SWR Radio Symphony Orchestra Stuttgart, and London Philharmonic. In October 2022, the San Francisco Symphony premiered Lindberg's Piano Concerto No. 3 with Yuja Wang as soloist.

Lindberg composed Chorale in 2002 as a companion piece for Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto. Both make use of the Lutheran chorale “Es ist genug” (It is enough), most famously set in 1723 by Johann Sebastian Bach in his Cantata 60, O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort (O eternity, you word of thunder). Linberg’s piece premiered in February 2002 with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Salonen.

—James M. Keller

Violin Concerto

Alban Berg

Born: February 9, 1885, in Vienna

Died: December 24, 1935, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1935

San Francisco Symphony Performances: First—May 1949. Dimitri Mitropoulos conducted with Joseph Szigeti as soloist. Most Recent—April 2022. Klaus Mäkelä conducted with Vilde Frang as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (both doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, gongs, tam-tam, snare drum, and bass drum), and strings

Duration: About 22 minutes

In February 1935, Louis Krasner, a Ukrainian-born, Boston-based violinist, approached the 50-year-old Alban Berg to request that he compose a concerto. The idea intrigued Berg, not least because of Krasner’s argument that what 12-tone music really needed to become popular was a genuinely expressive, heartfelt piece in an audience-friendly genre like a concerto.

That spring, the composer received word that on April 22 Manon Gropius, the 18-year-old daughter of Alma Mahler Werfel (widow of Gustav) and the well-known architect Walter Gropius, had died of polio. Berg had adored the girl since her earliest childhood, and, harnessing the creative energy that tragedy can inspire, he resolved to compose a musical memorial. Normally Berg required two years to write a large-scale work; the Violin Concerto was completed in less than four months. At the head of the manuscript he inscribed “To the Memory of an Angel.”

The Music

This piece, Berg’s only solo concerto, evolved according to the 12-tone principles that the composer had learned from Arnold Schoenberg and championed as only a great composer could—which is to say, by using those principles as a means toward articulating a unique world of expression.

The concerto’s most astonishing section is doubtless its conclusion: a set of variations on the chorale “Es ist genug! Herr wenn es Dir gefällt” (It is enough! Lord, if it pleases you). After the piece was already well along, Berg discovered that the opening notes of that chorale, which he knew through its harmonization in J.S. Bach’s Cantata No. 60, corresponded exactly to the final four notes of his tone row. Berg quickly realized that his current project enjoyed not just a musical connection to the chorale, but a poetic one as well, since the text of the chorale supremely expressed an emotion he was wanting to express about Manon Gropius’s inevitable resignation to untimely death:

It is enough!

Lord, if it pleases you,

Unshackle me at last.

My Jesus comes;

I bid the world goodnight.

I travel to the heavenly home.

I surely travel there in peace,

My troubles left below.

It is enough! It is enough!

Berg told his biographer Willi Reich that in the first movement he “had tried to translate the young girl’s characteristics into musical characters.” The second movement seems macabre and nightmarish. It begins in energetic, rhapsodic phrases that lead to a musical climax. This introduces the chorale melody, which sounds almost shocking in its 12-tone context. In the final bars, the solo violin, as if solving the puzzle presented by the two disparate approaches to harmony, articulates the entire 12-tone row simple and unadorned, from its lowest note to its highest, three octaves above. As the violin ascends in this ultimate gesture, the other instruments of the orchestra descend to their lowest registers, a world away from the soloist.

In a tragic turn that Berg could not have foreseen, the Violin Concerto was to be his last completed work. Shortly after composing it, the composer was annoyed by an abscess on his back, presumably the result of an insect bite. Treatment proved ineffective and blood poisoning ensued. Berg died at the end of the year in which he composed his concerto, a day before Christmas.

The philosopher Theodor Adorno, a one-time Berg pupil, pondered his own reaction to this work: “The Violin Concerto acquires an almost heartbreaking emotive power unlike almost anything else Berg ever wrote. He was granted something accorded only the very greatest artists: access to that sphere . . . in which the lower realm, the not quite fully formed, suddenly becomes the highest.”

—J.M.K.

The Firebird

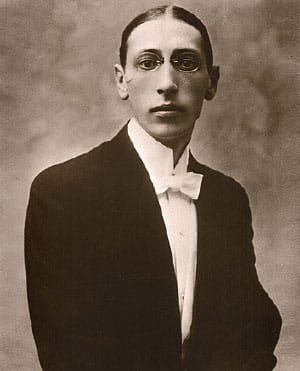

Igor Stravinsky

Born: June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, Russia

Died: April 6, 1971, in New York

Work Composed: 1909–10

SF Symphony Performances: First—April 1973. Seiji Ozawa conducted the complete ballet music (the 1919 Suite was first performed in June 1940, conducted by Pierre Monteux at the Golden Gate International Exposition). Most recent—October 2022. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2nd and 3rd doubling piccolo), 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (3rd doubling E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon), contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 Wagner tubas (offstage), 6 trumpets (3 offstage), 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, bells, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, and xylophone), 3 harps, piano, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 45 minutes

Just a few years before The Firebird premiered in Paris, Igor Stravinsky was an undistinguished law student in Saint Petersburg wishing he was a composer instead. By chance he met the son of Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who was then the most prominent and influential of Russian composers, ingratiated himself with the family, and soon was taking lessons with the master himself.

Meanwhile, Serge Diaghilev was developing plans to bring Russian art to Western European capitals, beginning with painting and sculpture, then experimenting with opera, and finally settling on ballet. Together with the dancer Michel Fokine, he established the Ballets Russes in Paris, which at first mostly choreographed to existing works by Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, and 19th-century Russian composers. To repurpose non-ballet music for dance was itself an innovative idea, but soon Parisians were clamoring for fresh sounds. Diaghilev and Fokine began to develop an ambitious new ballet with an original score for their French audience, and they paired two Russian folk characters—the magical Firebird and the evil Kashchei the Deathless—for the story.

The ballet follows Prince Ivan Tsarevich, who walks through the garden of Kashchei, a monstrous king. The prince sees the Firebird near a golden apple tree and captures it, only releasing it in exchange for a feather. Soon he meets 13 maidens and falls in love with one of them, who unfortunately turns out to be under Kashchei’s evil spell and lures the prince into a trap. The captured prince summons the Firebird with its feather, and the creature reveals that Kashchei’s immortality derives from a magical egg he keeps in a box. The prince smashes the egg, Kashchei dies, the maidens are liberated, and everyone rejoices.

At least three established composers turned down the project before Diaghilev tried the 27-year-old Stravinsky, who had previously only orchestrated a few Chopin piano pieces for the Ballets Russes. He was the last choice, and Diaghilev could not have had particularly high expectations for the untested composer. Stravinsky set to work writing in his Saint Petersburg apartment between December 1909 and May the following year, sometimes meeting with Fokine to improvise music and dance together.

The Music

The Firebird was Stravinsky’s first major piece, and it set him on course to write The Rite of Spring and other innovative works over the next five decades. An original voice already comes through in The Firebird, but current scholarship has emphasized its links to earlier Russian music—links that Stravinsky himself downplayed, not wanting to appear indebted to the country of his birth, or to the past.

But many of the melodies are borrowed from Russian folk music, and even his harmonic sleights-of-hand and modern orchestrational wizardries don’t stray far from those of Rimsky-Korsakov. The Firebird’s distinctive sound world is largely created through the contrast of murky, chromatic harmonies (representing supernatural evil) against bright, singable melodies (representing human good). It’s a vivid effect, but one borrowed from 19th-century Russian opera—not a 20th-century innovation. What really distinguishes Stravinsky is the shaping of melodies and his rhythmic sense—how he trims and arranges the sinewy phrases, creating jagged exclamations in fast sections and undulating tension in slow ones.

So what if The Firebird wasn’t quite as original as it might at first seem, when it has such an irresistible pull? The French critic Robert Brussel visited a piano rehearsal in Saint Petersburg in the winter of 1910. Perhaps the very first member of the public to hear it, he immediately recognized: “the moment [Stravinsky] began to play, the modest and dimly lit dwelling glowed with a dazzling radiance. By the end of the first scene, I was conquered: by the last, I was lost in admiration. The manuscript on the music stand, scored over with fine penciling, revealed a masterpiece.”

Stravinsky traveled to Paris that spring for the premiere at the Palais Garnier, and it was met with universal acclaim. Nearly every musical and literary figure in Paris attended the first night—and suddenly Stravinsky, who the day before had been a complete unknown, was shaking hands with Claude Debussy and Marcel Proust.

Stravinsky revisited The Firebird three times (in 1911, 1919, and 1945) to create suites for concert performance. Of these, the 1919 suite is the most frequently performed—but on today’s concert, we hear the complete ballet music as Stravinsky originally conceived it. In addition to being nearly twice as long as any of the suites, this version is more lavishly scored with a large brass section, three harps, and two keyboard players.

The music emerges from the dark in the lowest depths of the orchestra (Introduction), setting the stage as Kashchei’s cursed domain. In Scene I, the Firebird appears and dances against glittering violins, chirping clarinet and flutes (Dance of the Firebird). Soon Prince Ivan encounters the 13 princesses, who dance a khorovod—a Russian circle dance—warmly accompanied by solo violin, winds, and cello (Khorovod of the Princesses). The sun rises into the next day, and Kashchei and his retinue arrive and capture Prince Ivan. In a sudden eruption of timpani, brass, and xylophone, Kashchei is forced to dance (Infernal Dance), and is then subdued by the Firebird’s Lullaby, sung mostly by the bassoon. In the brief Scene II, peace is restored and Kashchei’s palace disappears, as the music slowly builds from the glow of a horn solo into a magnificent full-orchestra celebration.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

Listen Again

Hear Esa-Pekka Salonen and the San Francisco Symphony’s Grammy-nominated recording of The Firebird (SFS Media, 2024) on all major streaming services.

About the Artists

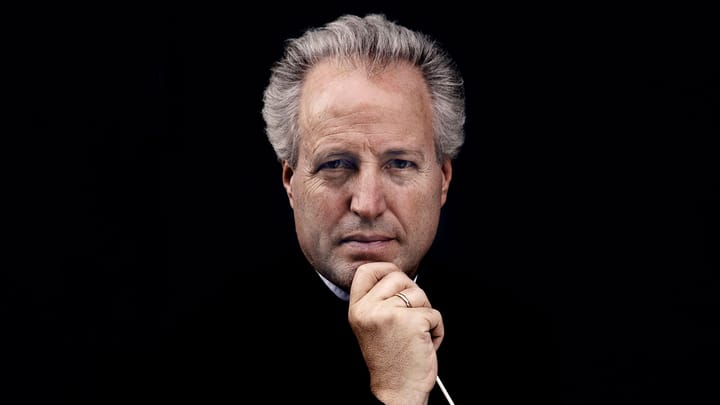

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Music Director

Known as both a composer and conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen is the Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony. He is the Conductor Laureate of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009, the Philharmonia Orchestra, where he was Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor from 2008 until 2021, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. As a member of the faculty of Los Angeles’s Colburn School, he directs the preprofessional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen cofounded, and until 2018 served as the Artistic Director of, the annual Baltic Sea Festival, which invites celebrated artists to promote unity and ecological awareness among the countries around the Baltic Sea.

Salonen has an extensive and varied recording career. Releases with the San Francisco Symphony include recordings of Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater, Bartók’s piano concertos, as well as spatial audio recordings of several Ligeti compositions. Other recent recordings include Strauss’s Four Last Songs, Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Dance Suite, and a 2018 box set of Mr. Salonen’s complete Sony recordings. His compositions appear on releases from Sony, Deutsche Grammophon, and Decca; his Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, and Cello Concerto all appear on recordings he conducted himself.

Esa-Pekka Salonen is the recipient of many major awards. Most recently, he was awarded the 2024 Polar Music Prize. In 2020, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) by the Queen of England.

Isabelle Faust

After winning the Leopold Mozart Competition and Paganini Competition at a very young age, Isabelle Faust soon began to perform regularly with orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, NHK Symphony, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Les Siècles, and Baroque Orchestra Freiburg. In addition to standard concerto repertoire, she has also performed Schubert’s Octet with historical instruments, Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat with Dominique Horwitz, and Kurtág’s Kafka Fragments with Anna Prohaskal; and given world premieres by Péter Eötvös, Brett Dean, Ondřej Adámek, and Rune Glerup. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut as a Shenson Young Artist in October 2014.

Highlights this season include performances with the Boston Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Bamberg Symphony, London Symphony, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Swedish Radio Symphony, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich. She was the 2024 artist in residence at Beethovenfest Bonn.

Faust shares a longstanding chamber music partnership with the pianist Alexander Melnikov, as well as trios with Tabea Zimmermann and Jean-Guihen Queyras. Faust and Melnikov have released recordings of sonatas for piano and violin by Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, among others. Her chamber collaborations include historical interpretations of Schubert’s Cello Quintet and String Quartet No. 15 in G major with Antoine Tamestit, Anne Katharina Schreiber, Jean-Guihen Queyras, and Christian Poltéra.

Faust’s recordings have been praised by critics and awarded the Diapason d’Or, Gramophone Award, Choc de l’année, and other prizes. She was named Instrumentalist of the Year by Opus Klassik in 2024. Recent recordings include Britten’s Violin Concerto with the Bavarian Radio Symphony, works for violin and orchestra by Pietro Locatelli with Il Giardino Armonico, and works for solo violin by Biber, Matteis, Pisendel, Vilsmayr, and Guillemain. She has also recorded Bach’s sonatas and partitas, as well as violin concertos by Beethoven and Berg.