In This Program

The Concert

Friday, October 3, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, October 4, 2025, at 7:30pm

Sunday, October 5, 2025, at 2:00pm

Gustavo Gimeno conducting

Timothy Higgins

Market Street, 1920s (2025)

San Francisco Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Edvard Grieg

Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 16 (1868)

Allegro molto moderato

Adagio

Allegro moderato molto e marcato

Javier Perianes

Intermission

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64 (1888)

Andante–Allegro con anima

Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza

Valse: Allegro moderato

Finale: Andante maestoso–Allegro vivace–

Moderato assai e molto maestoso–

Presto–Molto meno mosso

The commissioning of Timothy Higgins’s Market Street, 1920s is supported by the Ralph I. Dorfman Commissioning Fund.

These concerts are generously sponsored by the Athena T. Blackburn Endowed Fund for Russian Music.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Then come two classic works whose familiarity belies their ingenuity and originality. Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto, performed here by Javier Perianes, might feel like the very ideal of the genre, with its grand chords, singable melodies, and moody interplay of soloist and orchestra. Yet Grieg drew on resources specifically his own: a love for Schumann and Norwegian folk tunes, with a circuitous finale that could be a mini-concerto unto itself.

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 makes more out of a single theme than perhaps any other piece—taking it on a journey from a funereal opening to a blazing finale.

Market Street, 1920s

Timothy Higgins

Born: January 3, 1982, in Atlanta

Work Composed: 2024

SF Symphony Commission and World Premiere

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (small triangle, splash cymbal, ride cymbal, medium suspended cymbal, large cymbal, small tambourine, snare drum, tom-toms, bass drum, slapstick, ratchet, xylophone, and vibraphone), harp, and strings

Duration: About 8 minutes

Timothy Higgins joined the San Francisco Symphony as Principal Trombone in 2008 and holds the Robert L. Samter Chair. This fall he became principal trombone of the Chicago Symphony, but remains on leave from San Francisco for the current season, and will return as a soloist in May to give the US premiere of Jimmy López’s trombone concerto, Shift. Prior to joining the SF Symphony, he was acting second trombone with the National Symphony in Washington, DC, and studied at Northwestern University outside Chicago.

In addition to being one of America’s leading orchestral trombonists, Higgins is a composer and arranger. His work has frequently graced the Symphony’s holiday and all-brass concerts, as well as chamber music and SoundBox programs. In November 2021 he premiered his own Trombone Concerto with the Symphony and conductor Ludovic Morlot, following a commission instigated by Michael Tilson Thomas.

Market Street, 1920s is another SF Symphony commission, and it receives its world premiere this week. “The title of the piece comes from two places,” Higgins explained. “Firstly, the tone of the piece is reminiscent of black-and-white films of the old street cars traveling down Market Street in San Francisco.”

Second of all, the 1920s invoke Prohibition—an era that has some parallels with the drug policy debates of today, as well as a time when legislation and enforcement around alcohol was linked with anti-immigrant sentiment. Higgins wanted to make a musical nod toward San Francisco’s resistance against the Volstead Act—the 1919 law that provided a federal enforcement mechanism for the 18th Amendment’s liquor ban. The city government, for instance, instructed the police department at that time to turn a blind eye to speakeasies and bootleggers. “The resistance to national laws seemed very fitting for the tone of this work,” Higgins said.

From the Composer:

Market Street, 1920s is a wild and energetic piece for orchestra. It opens with two themes in different styles: one very academic, the other more popular. These two themes then argue for the remainder of the work, though it is less and less clear which side is making its point as the piece continues. Neither side of the argument is listening to the other, much like our current state of political discourse in America. What unfolds is a big farce that keeps interrupting itself and never fully finds resolution.

Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 16

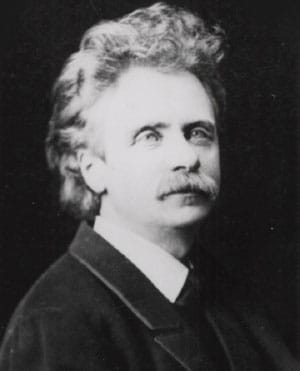

Edvard Grieg

Born: June 15, 1843, in Bergen, Norway

Died: September 4, 1907, in Bergen

Work Composed: 1868

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1912. Henry Hadley conducted with Adele Rosenthal as soloist. Most recent—February 2023. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted with Lang Lang as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 30 minutes

Why not begin by remembering the strangely mystical satisfaction of stretching my arms over the piano keyboard and bringing forth—not a melody. Far from it! No, it had to be a chord . . . both hands helping . . . Oh joy! . . . That was a success!

That is how Edvard Grieg recalled his first encounter with a piano at five years old (writing years later, of course, in a short autobiography). And why not begin a piano concerto the same way, at age 25? Grieg’s Piano Concerto channels that sense of childlike wonder and experimentation into an elegant Romantic form. Its virtuosity is natural, not finger-twisting; while by no means easy, it feels at ease.

Grieg became Norway’s foremost composer by way of the Leipzig Conservatory, which had been founded by Felix Mendelssohn 15 years earlier. His hometown teacher sent him off from Bergen with the words: “you are to go to Leipzig to become an artist!” The reality was drearier: egotistical professors, cutthroat classmates, homesickness, and poor health. “I was a dreamer with absolutely no talent for competition,” he recalled. “I was unfocused, not very communicative, and anything but teachable.”

Nonetheless, he picked up skills in harmony and composition, and a minor interaction changed the course of his life. Another student had a precious hand-written copy of Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto, and offered to trade it for a string quartet by Grieg (presumably to pass off as his own homework). Grieg loved Schumann, and accepted the deal so he could closely study the piece. He also had the chance to hear “the bewitching Clara Schumann” play her late husband’s concerto in Leipzig in November 1860, a performance he said was “indelibly impressed on my soul.”

It also made an impression on his own Piano Concerto, which he openly modeled on Schumann’s. Written in 1868, it became Grieg’s first international success, and remains his only orchestral piece in a largescale classical form (there are no Grieg symphonies, for instance). Having left the conservatory in 1862, he settled for a time in Copenhagen. “The veil fell off,” he said, “and suddenly my wondering eyes beheld the world of beauty which the Leipzig fog had hidden from me.” He married a cousin, Nina, and they moved back to Norway, settling in Kristiania (today called Oslo). He wrote the Piano Concerto while spending a summer in Denmark again, and premiered it in Copenhagen in April 1869.

The Music

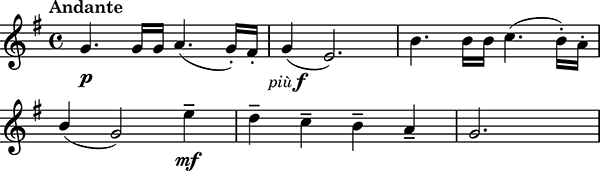

A timpani roll accelerates into the first piano chord and its ensuing downward cascade. Even if you are hearing the concerto for the first time, the opening will seem intuitive and familiar. The main theme is expressive but cool-headed; the more lyrical response is svelte and honest. The movement culminates in a bold cadenza—that five-year-old pianist has grown up to play a lot of chords now, still curious about the sound of each one.

The slow movement evokes a hymn, or hushed poetry. This time the piano enters with just two notes, four octaves apart, gently meeting the orchestra’s outreached hand. The soloist plays along for a time, but twice gets a bit feisty before settling back down tranquillo. Finally the pianist convinces the orchestra to support a more full-throated rendition of the hymn, and leaves satisfied.

The finale was inspired by Norwegian folk music, which Grieg was just beginning to investigate while clearing his head of all the German Romanticism he soaked up in Leipzig. It also has a curious form—almost a miniature concerto unto itself, with an early cadenza and false ending, followed by a sort of internal slow movement. Then back at a fast clip, the concerto fiddles and trumpets its way to the end.

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Opus 64

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born: May 7, 1840, in Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died: November 6, 1893, in Saint Petersburg, Russia

Work Composed: 1888

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1914. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—December 2021. Simone Young conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 50 minutes

All four movements of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony revolve around a mysterious theme stated plainly by the clarinets in its first moments. No other symphony develops an idea so tenaciously across such a large span (nearly 50 minutes), and with such clear trajectory: gloomy at the outset, but ending with one of the most triumphant climaxes in the entire orchestral repertoire.

Tchaikovsky’s previous two symphonies—the Fourth and the unnumbered Manfred Symphony—are both programmatic, meaning they are based on a story or extramusical concept. In a letter to his patron Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky described his Fourth Symphony as being about “fate, the force of destiny, which ever prevents our pursuit of happiness from reaching its goal.” Manfred was based on Lord Byron’s poem of the same name, following the suggestion of Tchaikovsky’s colleague Mily Balakirev. And of course Tchaikovsky was always a great creator of program music—from the Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet fantasy-overtures, which astonishingly distill each play’s dramatic essence, to his three sprawling fairy-tale ballets.

Altogether, this has made many scholars think the Fifth Symphony must have a program too, and that their job is to find out what it is. In April 1888, just before Tchaikovsky started work on the symphony, he wrote himself a note, musing vaguely:

Intr[oduction]. Total submission before fate, or, what is the same thing, the inscrutable designs of Providence.

Allegro. 1. Murmurs, doubts, laments, reproaches

against... XXX

2. Shall I cast myself into the embrace of faith???

A wonderful program, if only it can be fulfilled.

But none of this corresponds to the Fifth Symphony in the form completed that August, never mind that the “fate” idea would seem to retread ground covered in the Fourth Symphony. Some musicologists have tried to establish a connection between the binding “motto” theme and the contours of a Russian Orthodox hymn “Khristos Voskrese” (“Christ is risen!”—implying, perhaps, that the symphony’s journey from sorrow to triumph depicts the resurrection). Others have suggested a connection with Mikhail Glinka’s patriotic chorus “Slav’sya” (“Glory!” from the opera A Life for the Tsar—implying who knows what). The similarities are generic enough to suggest a search for something that isn’t there. It seems Tchaikovsky so convincingly realized an archetypal musical form that some people have trouble accepting it as a pure abstraction.

The composer conducted the premiere in Saint Petersburg on November 17, 1888; the next month he led it in Moscow, and soon it was receiving performances in Germany and the United States. Today, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony is a beloved crowd-pleaser, but in the 1890s it was considered dubiously “ultra-modern,” or treated as an exotic specimen from the European fringe—sometimes in racist terms. “The second movement showed the eccentric Russian at his best,” opined New York’s Musical Courier, “while in the last movement, the composer’s Calmuck blood got the better of him, and slaughter, dire and bloody, swept across the storm-driven score.” (Kalmyks are in fact a mostly Buddhist ethnic group in Russia, descended from the Mongols, to whom Tchaikovsky was not related.)

The composer himself, always prone to doubt, shifted his appraisal of his work. First, he happily reported that most of his friends adored the premiere, but a month later he wrote to Nadezhda von Meck:

After each performance I become more and more convinced that my new symphony is a failure, and the consciousness of all this—and also of what it may indicate regarding the weakening of my creative powers—depresses me greatly. It seems the symphony is too garish, too massive, too patchy and insincere, too long, and generally of very little appeal.

Yet by March 1889, he updated her, “The Fifth Symphony was again performed magnificently, and I have started to love it again; my earlier judgement was undeservedly harsh.”

The Music

The first movement begins with the dark “motto” theme in unison clarinets. Tchaikovsky elaborates on it until he leads into a light waltz-like idea. At the end, the motto theme comes back, and then dissolves in a rasp from the cellos and double basses.

The second movement emerges from the darkness with which the first movement ends. The strings begin with a reverent chorale, and then the horn enters with a lyrical solo. The second theme is both sunny and deeply felt. Twice, however, this atmosphere is interrupted by an imposing version of the motto theme. The third movement is a true waltz—a more fully-formed version of what we heard in the first movement. This is the most fanciful part of the symphony, moments are almost humorous. At the very end the motto theme returns as an echo in the clarinets and bassoons, accompanied by pizzicato strings.

The finale opens with the indelible theme. It is less ominous than ever before, and soon transforms into a confident march. The dramatic apotheosis and ear-ringing coda make an incredibly satisfying ending—for the brass section and audience and alike.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

The Grieg Piano Concerto note originally appeared in the program book of the St. Louis Symphony.

Tchaikovsky and Grieg

Tchaikovsky and Grieg got to know each other in 1888, around the time Tchaikovsky was writing his Fifth Symphony. They were both visiting Leipzig and met at a New Year’s Day party also attended by Johannes Brahms.

They admired each other’s music and Tchaikovsky considered dedicating his Fifth Symphony to Grieg, though he ended up dedicating the Hamlet Fantasy-Overture to him instead (perhaps associating Grieg with the play’s Nordic setting). They communicated in limited German—their only mutual language.

“You cannot imagine what joy my meeting with you has given me,” Grieg wrote to Tchaikovsky that April. “No, not joy, but much more! You have left such a strong impression on me both as an artist and as a human being.”

The following September, Tchaikovsky invited Grieg to perform his A-minor Piano Concerto in Moscow, but the concert never happened. In that letter, Tchaikovsky reported, “I have written a new symphony” (the Fifth), adding “It is so difficult for me to write in German; there is much I should like to tell you—but I cannot. Until we meet again, my dear, good, most esteemed friend!”

Tchaikovsky died unexpectedly five years later and they never did.

About the Artists

Gustavo Gimeno

Gustavo Gimeno has been music director of the Toronto Symphony since the 2020–21 season and has committed to the orchestra through 2030. This year also marks his inaugural season as music director of Madrid’s Teatro Real. He was previously music director of the Luxembourg Philharmonic.

This season, Gimeno debuts with the New York Philharmonic and returns to the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Recent highlights include appearances with the Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Berlin Philharmonic, Munich Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, and NHK Symphony.

In February 2025, Gimeno and the TSO released their second album together on Harmonia Mundi, featuring Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella and Divertimento as well as the world premiere recording of Kelly-Marie Murphy’s Curiosity, Genius, and the Search for Petula Clark. Their first album for the label featured Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie and won the Juno Award for Classical Album of the Year (Large Ensemble). With the Luxembourg Philharmonic, he developed an extensive discography with Pentatone.

In March 2025, Gimeno was appointed a commander of the Order of Civil Merit by King Felipe VI of Spain, and following his tenure with the Luxembourg Philharmonic, Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg made Gimeno an officer in the Order of Civil and Military Merit of Adolph of Nassau. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in November 2021.

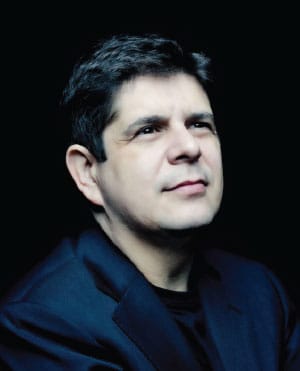

Javier Perianes

Javier Perianes’s highlights include concerts with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, National Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Montreal Symphony, Vancouver Symphony, London Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Vienna Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, NDR Elbphilharmonie, Danish National Symphony, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Budapest Festival Orchestra, and Yomiuri Nippon Symphony. In recital, he has appeared at Wigmore Hall, and has also performed at the BBC Proms, Lucerne Festival, Martha Argerich Festival, Bravo! Vail, Blossom Music Festival, and Ravinia Festival, among others.

Perianes records exclusively for Harmonia Mundi and his most recent releases feature Granados’s Goyescas and Chopin’s Sonatas Nos. 2 and 3 interspersed with mazurkas. He also recently released Jeux de miroirs, centered around Ravel’s Concerto in G major with Orchestre de Paris, also including both piano and orchestral versions of Le tombeau de Couperin and Alborada del gracioso. Together with violist Tabea Zimmermann, Perianes released Cantilena in 2020, an album celebrating music from Spain and Latin America.

Perianes was awarded the National Music Prize in 2012 by the Ministry of Culture of Spain and named Artist of the Year at the International Classical Music Awards in 2019. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in June 2015.