In This Program

- The Concert

- At a Glance

- Program Notes

- From Manfred Honeck

- Mozart’s Requiem: Texts and Translations

- About the Artists

- About San Francisco Symphony

The Concert

Thursday, February 26, 2026, at 7:30pm

Friday, February 27, 2026, at 7:30pm

Sunday, March 1, 2026, at 2:00pm

Inside Music Talk with The Very Rev. Dr. Malcolm Clemens Young, Dean of Grace Cathedral

On stage Thursday and Friday at 6:30pm, Sunday at 1:00pm

Exhibit: Requiem Reflections

On display in the First Tier Lobby

Manfred Honeck conducting

Ludwig van Beethoven

Coriolan Overture, Opus 62 (1807)

Joseph Haydn

Symphony No. 93 in D major (1791)

Adagio–Allegro assai

Largo cantabile

Menuetto: Allegro

Presto ma non troppo

Intermission

Candles are available during intermission.

Audience members are invited to place one on the edge of the stage in memory of someone who has lit the way.

Mozart’s Requiem is presented in the context of a funeral liturgy, as conceived by Manfred Honeck. Learn more

Please refrain from applause until the very end.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Requiem in D minor, K.626 (1791)

- Three Bell Strokes

- Gregorian Chant: Requiem aeternam

- Reading: Letter from Mozart to his father (April 4, 1787)

- Masonic Funeral Music, K.477 (1785)

- Gregorian Chant: Domine, exaudi orationem meam

- Laudate Dominum from Vesperae solennes de Confessore, K.339/5 (1780)

- Gregorian Chant: In quacumque die

- Reading: “Who Knows Where the Stars Stand” by Nelly Sachs

- Reading: “When in the Late Spring” by Nelly Sachs

Introitus: Requiem

Kyrie

- Reading: Book of Revelation 6:8–17

Sequenz

Dies irae

Tuba mirum

Rex tremendae

Recordare

Confutatis

Lacrimosa

- Gregorian Chant: Christus factus est

- Reading: Book of Revelation 21:1–7

Offertorium

Domine Jesu

Hostias

Lacrimosa [fragment, reprise]

- Ave verum corpus, K.618 (1791)

- Three Bell Strokes

Ying Fang soprano

Sasha Cooke mezzo-soprano

David Portillo tenor

Stephano Park bass

Adrian Roberts narrator

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

St. Dominic’s Schola Cantorum

Simon Berry director

Lead support for the San Francisco Symphony Chorus this season is provided through a visionary gift from an anonymous donor.

Inside Music Talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

Opening the program are two other late classical works by Mozart’s senior and junior colleagues: Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 93, written during the composer’s triumphant stay in London, and Ludwig van Beethoven’s dramatic Coriolan Overture, composed for a play about an ambitious Roman general.

Coriolan Overture, Opus 62

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1807

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1912. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—March 2017. Marek Janowski conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 8 minutes

Although the play for which it was written sank into immediate obscurity, Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture survived to grace the symphonic repertoire. Less a prelude to the drama than an encapsulation of it, the eight-minute composition serves as an early example of what would later be called the symphonic poem.

Beethoven composed the Coriolan Overture in 1807 to accompany a five-act tragedy by that name, which was written by his friend Heinrich von Collin. Even before he read Collin’s play, Beethoven was familiar with the plot, thanks to Shakespeare’s Coriolanus and Plutarch’s Parallel Lives. In Collin’s more introspective version, the general Coriolan feels so grievously disrespected by his fellow Romans that he aligns himself with the enemy Volscians. As he prepares to take vengeance on his former people, his mother and wife talk him out of fighting. Unable to resolve his ethical and emotional conflict, he falls on his own sword. Beethoven, who bitterly resented the Viennese tastemakers of his day, likely identified with the tormented hero.

Like his groundbreaking Eroica Symphony from 1803, the Coriolan overture is cast in the heroic style, a Romantic expression of dynamic struggle. The vividly orchestrated work follows the emotional contours of the play while still observing the basic rules of sonata form. Beethoven’s choice of C minor was no accident; the key represented for him both heroism and pathos. The overture starts with three loud unison chords voiced by the strings; the orchestra replies to each volley with a higher chord, punctuated by a tense silence. Next, a surging, restless figure in the home key evokes the hero’s defiance and his indomitable will. A more lyrical secondary theme in E-flat major represents the feminine plea for peace. After a brief and fiery development section, Beethoven depicts Coriolan’s interior conflict in the recapitulation. The end of the overture foreshadows the hero’s suicide as the searing intensity of the introductory material subsides to an uneasy gloom. A contemporary reviewer described the overture as calculated “ to produce much more of a profound than a radiant effect.”

Symphony No. 93 in D major

Joseph Haydn

Born: March 31, 1732, in Rohrau, Lower Austria

Died: May 31, 1809, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1791

SF Symphony Performances: First—March 1951. Guido Cantelli conducted. Most recent—October 2014. Christian Zacharias conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 20 minutes

When his main patron, Prince Nicolaus Esterházy, died in 1790, Haydn was 58 years old. The son of a wheelwright and a cook, he refused to rest on his laurels—or even rest. After serving the Esterházy court for 28 years, he eagerly moved to Vienna, where he hoped to reach new audiences and potential backers. Soon after his arrival, he met the German-born violinist and impresario Johann Peter Salomon, who offered him a handsome sum to present six new symphonies in London. Although Haydn had never before traveled outside the Habsburg Realm, he spent most of the 1791–92 concert season in the English capital, writing and overseeing performances of the first half of what would one day be known as the London Symphonies, or Symphonies 93 through 104. The numbers are somewhat misleading: the symphonies that we know today as Nos. 95 and 96 actually debuted first in January 1791. Symphony No. 93 was the third.

Haydn composed Symphony No. 93 in London, most likely in late spring or summer 1791. The first performance, on February 17, 1792, kicked off the second season of Salomon’s concerts. Salomon led the orchestra as concertmaster, and Haydn played harpsichord. After the first batch of symphonies proved wildly popular, Haydn was immediately hired to write another six, bringing him back to London in 1794.

The Music

Like all the London Symphonies, Symphony 93 is in four movements. The first opens with a 20-measure introduction, marked Adagio. After an emphatic unison D major, the harmonies flatten and dip unexpectedly into minor modes before the Allegro portion of the movement begins. The principal theme emerges promptly and undergoes a series of harmonic makeovers; the secondary theme, a boisterous Ländler-like dance tune, turns itself inside out and upside down before Haydn lovingly sends it to bed in the home key.

Set in G major, the lilting Largo cantabile lives up to its tempo indication—slow and singing. The elevated and refined mood of the variations ascends to a courtly oboe solo, and then a vulgar bassoon erupts in a dissonant fortissimo fart. Haydn loved a good prank.

The third-movement minuet is no ballroom snoozer. Instead, it’s another raucous Ländler—or even a proto-scherzo, akin to the future Beethovenian model. At any rate, with its quicksilver rhythmic shifts and racing tempo, this minuet is audaciously undanceable, pitting strings-only serenity against timpani-fueled fanfares. The Presto finale, in Rondo form, continues the earthy humor with touches of strategic mayhem.

Requiem in D minor, K.626

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1791

SF Symphony Performances: First—April 1965. Josef Krips conducted the Süssmayr completion with the Stanford University Chorus. Pierrette Alarie, Tatiana Troyanos, Leopold Simoneau, and Donald Gramm were soloists. Most recent—February 2011. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the Süssmayr completion with the San Francisco Symphony Chorus. Kiera Duffy, Sasha Cooke, Bruce Sledge, and Nathan Berg were soloists.

Instrumentation: soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass, chorus, 2 basset horns, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, organ, and strings. This version by Manfred Honeck adds a narrator, bells, and an offstage chorus of low voices.

Duration: About 60 minutes

The Requiem is beautiful, like everything Mozart made, but it can also be profoundly scary. It’s a pity that the word “awesome” feels stale from overuse. If anything deserves the adjective, it’s Mozart’s final work, an unfinished musical setting of the Latin Mass for the Dead.

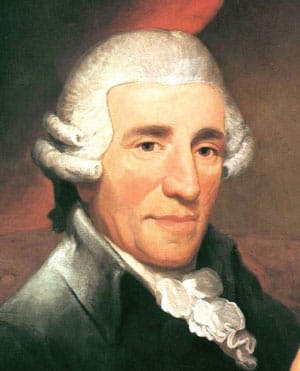

Scholars and general listeners have spent more than two centuries trying to tease out the truth from the tangle of lies surrounding the Requiem’s composition. Here’s what we know: in July 1791, Mozart accepted a commission for a Requiem Mass from a mysterious emissary. The anonymous patron was the recently widowed Count Franz von Walsegg, an amateur musician who liked to commission professional composers and then claim their work as his own—though Mozart probably didn’t know that. Although the cash-strapped composer accepted half the money in advance, he didn’t start working on the Requiem right away. He wasn’t procrastinating so much as putting out fires. He needed to finish two previously commissioned operas in time for their premieres, as well as the Clarinet Concerto and a cantata for his fellow Freemasons.

He appears to have started on the Requiem in October, and, contrary to a persistent myth, he wasn’t preoccupied with his impending death. His letters to his wife, Constanze, are affectionate and optimistic, full of references to future schemes and projects. He had no reason to believe he had less than two months to live. But on November 20 he took to his sickbed, and on December 5, at about 1:00am, he died, most likely as a result of acute rheumatic fever or kidney failure. (The idea he was poisoned by an envious Antonio Salieri is pure fiction, first popularized by Alexander Pushkin in his 1830 play Mozart and Salieri, and perpetuated in Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play Amadeus and subsequent film.) According to some reports, Mozart’s last physical movement involved mouthing a timpani part so that his pupils could add it to the score.

Because Mozart left the score unfinished, the legitimacy of the completion has always been questioned. Everyone agrees Mozart finished the first movement (Introitus) and most of the Kyrie, including its astounding double fugue. He also left drafts and sketches for the Sequenz, which opens with the Dies irae and ends with the Lacrimosa, and the Offertorium. Constanze insisted he gave his assistants clear instructions for the remainder—but she may have been motivated to say so in order to collect the remaining fee from Count Walsegg.

We do know that the Requiem was finished in great secrecy by Franz Xaver Süssmayr, Mozart’s former student and sometime copyist, about two months after the composer’s death and after two other former pupils had abandoned the job. Although Süssmayr was present during Mozart’s final weeks, he wasn’t Constanze’s first (or second) choice: her husband, chronically irritated by lesser talents, had called him an “ass” and a “blockhead.” Robert Schumann later complained his version was “not merely corrupt but wholly inauthentic except for a few numbers,” and many contemporary performers and scholars feel the concluding Süssmayr movements deviate noticeably from Mozart’s style.

Imagining Mozart’s Funeral

For this performance, Manfred Honeck offers a different, dramatic presentation—an imagined, recontextualized version of Mozart’s own funeral that leaps backward and forward in time. Honeck retains only the portions of the Requiem that Mozart had a significant hand in, discarding the Süssmayr-penned movements following the Offertorium (but maintaining Süssmayr’s presumed orchestrational contributions in earlier sections, as well as his completion of the Lacrimosa). To this, Honeck adds three earlier Mozart works: the Masonic Funeral Music, K.477; the Laudate Dominum from Vesperae solennes de confessore, K.339/5; and Ave verum corpus, K.618—a rapt and reverent meditation on Christ’s suffering. Honeck also intersperses Gregorian chants, Biblical readings, and poems by the German poet, playwright, and Holocaust survivor Nelly Sachs.

After the Offertorium, Honeck reprises the Lacrimosa—this time stopping after just eight bars exactly where Mozart’s manuscript cuts off: a shocked pause to mark the composer’s death. The performance resumes, but very quietly, with Ave verum corpus. The Austrian death bell tolls thrice, and the service ends.

—René Spencer Saller

From Manfred Honeck

As a conductor, I always wonder under what circumstances and with what intentions a composer wrote a particular piece—crucial aspects for any interpretation. In the case of Mozart’s Requiem, the story is particularly complex and mysterious. A secret messenger conveyed the commission from Count Walsegg, who intended to pass off the work as his own in memory of his deceased wife. The secrecy surrounding the commission, combined with Mozart’s deteriorating health, created an almost mythical aura around the work. Mozart, who had composed over 600 works but never a Requiem, agreed to the commission due to financial difficulties. However, he died before completing it, leaving behind sketches and drafts that were later finished by other composers, most notably his student Franz Xaver Süssmayr.

Since we will never know how Mozart himself would have completed the work, I have chosen to perform only the parts that he composed himself. My concept expands the Requiem through elements that reflect Mozart’s time and personal thoughts on death. For example, in Mozart’s era, the tolling of death bells was a significant ritual upon the passing of an individual. I incorporate this by beginning and ending the performance with three bell strokes in the key of D—the same key as the Requiem itself.

In addition, Gregorian chants, an integral part of the liturgy of Mozart’s time, are woven into the performance. These are sung by a separate off-stage male choir to create a spatial contrast. Another important textual component is Mozart’s letter to his father from April 4, 1787, in which he reflects on death not as something to be feared, but as a “true best friend of man” that brings peace and consolation. This idea resonates in the inclusion of his motet Ave verum corpus, composed only a few months before his death. The work exudes a sense of acceptance and tranquility, reinforcing the Requiem’s thematic depth.

I also aim to connect Mozart’s work to our own time. The inclusion of two poems by the Jewish poet Nelly Sachs, “Wer weiss, wo die Sterne stehen” (Who Knows Where the Stars Stand) and “Wenn im Vorsommer” (When in the Late Spring), serves as a bridge to the modern era, reflecting on the tragedies of the 20th century, particularly the Holocaust. Similarly, excerpts from the Book of Revelation provide an apocalyptic vision that aligns with the Dies irae sequence in the Requiem. These readings are placed precisely at moments in the work where words and music intertwine in meaning.

The final moments of the performance return to the Lacrimosa, the last passage Mozart wrote before his death. This fragment, consisting of only eight bars, is heard earlier in the Requiem but is repeated here, creating a sense of unfinished eternity. It is then followed by Ave verum corpus, providing a sense of peace and closure. Finally, the three bell strokes sound once more, bringing the work full circle.

This concept intertwines Mozart’s music, historical context, and reflections on death, offering a deeply personal yet universal experience that transcends time.

—MH

Mozart’s Requiem: Texts and Translations

Gregorian Chant: Requiem aeternam

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

et lux perpetua luceat eis

—

Grant them eternal rest, O Lord,

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

Gregorian Chant: Domine exaudi orationem meam

Domine exaudi orationem meam

et clamor meus ad te veniat.

—

O Lord, hear my prayer,

and let my cry come to you.

Laudate Dominum from Vesperae solennes de Confessore, K.339/5

Laudate Dominum omnes gentes:

laudate eum omnes populi.

Quoniam confirmata est super nos misericordia ejus:

et veritas Domini manet in aeternum.

Gloria Patri, et Filio,

et Spiritui Sancto.

Sicut erat in principio,

et nunc et semper,

et in saecula saeculorum.

Amen.

—

Praise the Lord, all nations:

praise him, all people.

For his mercy is confirmed upon us:

and the truth of the Lord remains forever.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son,

and to the Holy Spirit.

As it was in the beginning,

is now, and ever shall be,

world without end.

Amen.

Gregorian Chant: In quacumque die

In quacumque die invocavero te,

velociter exaudi me.

—

On whatever day I call upon you,

hear me quickly.

Introitus: Requiem

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine,

et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Te decet hymnus, Deus, in Sion,

et tibi reddetur votum in Jerusalem.

Exaudi orationem meam.

Ad te omnis caro veniet.

—

Grant them eternal rest, O Lord;

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

There shall be singing unto you in Zion,

and prayer shall go up to you in Jerusalem.

Hear my prayer.

Unto you all flesh shall come.

Kyrie

Kyrie eleison.

Christe eleison.

Kyrie eleison.

—

Lord have mercy.

Christ have mercy.

Lord have mercy.

Sequenz

Dies irae

Dies irae, dies illa

solvet saeclum in favilla,

teste David cum Sibylla.

Quantus tremor est futurus,

quando Judex est venturus

cuncta stricte discussurus!

—

This day, this day of wrath

shall consume the world in ashes,

so said David and the Sibyl.

Oh, what great trembling there will be

when the Judge will appear

to examine everything in strict justice!

Tuba mirum

Tuba mirum spargens sonum

per sepulchra regionum,

coget omnes ante thronum.

Mors stupebit et natura,

cum resurget creatura

judicanti responsura.

Liber scriptus proferetur,

in quo totum continetur,

unde mundus judicetur.

Judex ergo cum sedebit,

quidquid latet apparebit,

nil inultum remanebit.

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

Quem patronum rogaturus,

cum vix justus sit sicurus?

—

The trumpet, sending its wondrous sound

across the graves of all lands,

shall drive everyone before the throne.

Death and nature shall be stunned

when all creation rises again

to stand before the Judge.

A written book will be brought forth,

in which everything is contained,

from which the world will be judged.

So when the Judge is seated,

whatever is hidden shall be made known,

nothing shall remain unpunished.

What shall such a wretch as I say then?

To which protector shall I appeal,

when even the just man is barely safe?

Rex tremendae

Rex tremendae majestatis,

qui salvandos salvas gratis,

salva me, fons pietatis!

—

King of awesome majesty,

who freely saves those worthy of salvation,

save me, fount of pity!

Recordare

Recordare, Jesu pie,

quod sum causa tuae viae,

ne me perdas illa die

Quaerens me, sedisti lassus,

redemisti crucem passus;

tantus labor non sit cassus.

Juste judex ultionis,

donum fac remissionis

ante diem rationis.

Ingemisco tamquam reus,

culpa rubet vultus meus,

supplicanti parce, Deus.

Qui Mariam absolvisti

et latronem exaudisti,

mihi quoque spem dedisti.

Preces meae non sunt dignae,

sed tu bonus fac benigne,

ne perenni cremer igne.

Inter oves locum praesta

et ab hoedis me sequestra,

statuens in parte dextra.

—

Recall, dear Jesus,

that I am the reason for your time on earth,

do not cast me away on that day.

Seeking me, you did sink down wearily,

You have saved me by enduring the cross;

such travail must not be in vain.

Righteous judge of vengeance,

award the gift of forgiveness

before the day of reckoning.

I groan like the sinner that I am,

guilt reddens my face,

Oh God, spare the supplicant.

You, who pardoned Mary

and heeded the thief,

has given me hope as well.

My prayers are unworthy,

but you, good one, in pity

let me not burn in the eternal fire.

Give me a place among the sheep

and separate me from the goats,

let me stand at your right hand.

Confutatis

Confutatis maledictis,

flammis acribus addictis,

voca me cum benedictis.

Oro supplex et acclinis,

cor contritum quasi cinis,

gere curam mei finis.

—

When the damned are cast away

and consigned to the searing flames,

call me to be with the blessed.

Bowed down in supplication I beg you,

my heart as though ground to ashes:

help me in my last hour.

Lacrimosa

Lacrimosa dies illa

qua resurget ex favilla

judicandus homo reus;

huic ergo parce Deus.

Pie Jesu, Domine,

dona eis requiem.

Amen.

—

Oh, this day full of tears

when from the ashes arises

guilty man, to be judged:

Oh Lord, have mercy upon him.

Gentle Lord Jesus,

grant them rest.

Amen.

Gregorian Chant: Christus factus est

Christus factus est pro nobis obediens

usque ad mortem, mortem autem crucis.

—

Christ became obedient for us unto death,

even to the death, death on the cross.

Offertorium

Domine Jesu

Domine Jesu Christe, rex gloriae,

Libera animas omnium fidelium defunctorum

de poenis inferni

et de profundo lacu.

Libera eas de ore leonis,

ne absorbeat eas tartarus,

ne cadant in obscurum;

sed signifer sanctus Michael

representet eas in lucem sanctam,

quam olim Abrahae promisisti

et semini ejus.

—

Lord Jesus Christ, King of Glory,

deliver the souls of the faithful departed

from the pains of hell

and the bottomless pit.

Deliver them from the jaws of the lion,

lest hell engulf them,

lest they be plunged into darkness;

but let the holy standard-bearer Michael

lead them into the holy light,

as you did promise Abraham

and his seed.

Hostias

Hostias et preces tibi, Domine,

laudis offerimus,

tu suscipe pro animabus illis,

quarum hodie memoriam facimus:

quam olim Abrahae promisisti

et semini ejus.

—

Lord, in praise we offer to you

sacrifices and prayers,

receive them for the souls of those

whom we remember this day:

as you did promise Abraham

and his seed.

Lacrimosa [fragment, reprise]

Lacrimosa dies illa

qua resurget ex favilla

judicandus homo reus...

—

Oh, this day full of tears

when from the ashes arises

guilty man, to be judged...

Ave verum corpus, K.618

Ave, verum corpus,

natum de Maria virgine:

Vere passum, immolatum

in cruce pro homine;

Cujus latus perforatum

unda fluxit et sanguine.

Esto nobis praegustatum

in mortis examine.

—

Hail, true flesh,

born of the Virgin Mary:

Who has truly suffered,

broken on the cross for man;

from whose pierced side

flowed water and blood.

Be for us a foretaste

of the trial of death.

Head to the First Tier Lobby for an exhibit connecting Mozart’s Requiem with the universal questions it stirs.

About the Artists

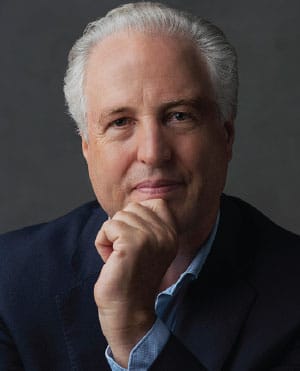

Manfred Honeck

Manfred Honeck is currently in his 18th season as music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony. His tenure, extended through the 2027–28 season, has seen the PSO flourish both artistically and as a cultural ambassador for Pittsburgh. The orchestra’s appearances under his leadership include Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, as well as the BBC Proms, Salzburg Festival, Musikfest Berlin, and Lucerne Festival. His recordings with the PSO on the Reference Recordings label have received multiple Grammy Award nominations, including a win for Best Orchestral Performance in 2018. They recently released the album Requiem: Mozart’s Death in Words and Music, encompassing Honeck’s interpretation of Mozart’s Requiem.

Born in Austria, Honeck completed his musical training at the University of Music in Vienna. His many years of experience as a violist in the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna State Opera Orchestra have had a lasting influence on his work as a conductor, and his art of interpretation is rooted in a desire to venture deep beneath the surface of the music. He has since served as a principal conductor of the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony, music director of Norwegian National Opera, principal guest conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic and Czech Philharmonic, and chief conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony. In 2023, he was appointed honorary conductor by the Bamberg Symphony, following decades of close collaboration.

As a guest conductor, Manfred Honeck is a regular presence with the Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Dresden Staatskapelle, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich, London Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, Accademia di Santa Cecilia Rome, and has conducted all the major American orchestras. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in May 2017.

Honeck holds honorary doctorates from several American universities, was named an honorary professor by the president of Austria, and was named 2018 “artist of the year” by the International Classical Music Awards.

Ying Fang

This season, Ying Fang makes her house debut at Houston Grand Opera, appears with Vienna State Opera and Philadelphia Orchestra (in Philadelphia and at Carnegie Hall), and records Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Pittsburgh Symphony and Manfred Honeck. Further highlights include the Vienna Philharmonic, Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, and Salzburg Festival. A noted Mozart interpreter, she debuted last season at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden, as Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro; debuted at the Bavarian State Opera as Pamina in Die Zauberflöte; and debuted at San Francisco Opera as Ilia in Idomeneo. She frequently appears at the Metropolitan Opera and is a former member of the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. She made her San Francisco Symphony debut with Handel’s Messiah in December 2018.

A native of Ningbo, China, Fang is the recipient of the Martin E. Segal Award, Hildegard Behrens Foundation Award, Rose Bampton Award of the Sullivan Foundation, Opera Index Award, and first prize of the Gerda Lissner International Vocal Competition. In 2009, she became one of the youngest singers to win the China Golden Bell Award for Music. She studied at the Juilliard School and Shanghai Conservatory.

Sasha Cooke

Two-time Grammy Award–winning mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke has sung at the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, English National Opera, Seattle Opera, Opéra National de Bordeaux, and Gran Teatre del Liceu, among others, and with more than 80 symphony orchestras worldwide. This season, she appears with Houston Grand Opera, Seattle Opera, the Chicago Symphony at the Ravinia Festival, Philadelphia Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Boston Symphony Chamber Players, Vienna Symphony, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony, and Sydney Symphony.

Cooke made her San Francisco Symphony debut in June 2009 and became a Shenson Young Artist in January 2010. She toured Europe with Michael Tilson Thomas and the Symphony, premiered MTT’s Meditations on Rilke (captured on a Grammy-winning SFS Media release), and recorded two of MTT’s songs on Grace: The Music of Michael Tilson Thomas. Last season, she sang at MTT’s 80th Birthday Concert as well as Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 with Esa-Pekka Salonen. She returns later this season for Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’été with Elim Chan (June 5–6).

Cooke is a graduate of Rice University and the Juilliard School. She also attended the Music Academy of the West, Aspen Music Festival, Ravinia Festival’s Steans Music Institute, Wolf Trap Foundation, Marlboro Music Festival, and the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program.

David Portillo

David Portillo appears this season with the Dutch National Opera, Seattle Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Baroque, and the English Concert. In recent seasons, he has also appeared with the Metropolitan Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, Opera Theatre of St. Louis, Santa Fe Opera, Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, and Bard Music Festival. In Europe, he has performed at the Vienna State Opera, Theater an der Wien, Frankfurt Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, Glyndebourne Festival, and Salzburg Festival. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Portillo is an alumnus of the Ryan Opera Center at Lyric Opera of Chicago, Merola Opera Program at San Francisco Opera, and Wolf Trap Opera. In 2024, he was awarded the Sphinx Medal of Excellence.

Stephano Park

Stephano Park’s engagements this season include Santa Fe Opera, Royal Danish Opera, Calgary Opera, the Milwaukee Symphony, and Chicago Symphony for Mozart’s Requiem with Manfred Honeck. He has also performed with the Baltic Opera Festival, Korean National Opera, and Korean National Symphony. Park recently completed his second season as part of the Vienna State Opera’s studio, where his roles have included Walter Furst in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, Lodovico in Verdi’s Otello, Sid in Puccini’s La fanciulla del West, the Jailer in Puccini’s Tosca, and Hans Schwarz in Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with these performances.

Park was the winner of the 2023 Operalia in Cape Town, South Africa. He trained at Seoul National University and continues his studies at Vienna’s University of Music and Performing Arts.

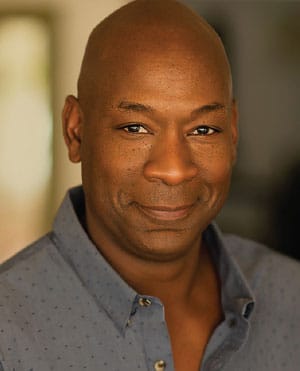

Adrian Roberts

Adrian Roberts has been a professional actor for more than 30 years, appearing in many local and regional theater productions. His Bay Area credits include George in Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? and Prospero in The Tempest at Oakland Theater Project, Martin Luther King Jr. in The Mountaintop at Theater Works, King Basillio in Life Is A Dream and Claudius in Hamlet at Cal Shakes, Willy in “Master Harold”... and the Boys at the Aurora Theater, and the title role in Macbeth at African American Shakes. His regional credits include Ken in Playboy of the West Indies at Lincoln Center, Asagai in Raisin in the Sun at the Huntington Theater, and three seasons at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Roberts’s television credits include Scrubs, Criminal Minds, Chance, and the web series Normal Ain’t Normal. He has also appeared in the video game NBA 2K, 2022, 2024, and 2025. He is a graduate of ACT’s MFA program and makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

Under Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011. She recently extended her contract with the SF Symphony through the 2028–29 season.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

St. Dominic’s Schola Cantorum

Based at St. Dominic’s Catholic Church in San Francisco, the Schola Cantorum is a group of singers and instrumentalists, both professional and volunteer, dedicated to performing the repertory of what the Second Vatican Council described as “the vast treasury of sacred music.” The choir performs a full spectrum of liturgical music, including Gregorian chant, polyphonic mass settings, and motets and anthems. They perform at the Solemn Mass every Sunday and have recorded several CDs of music by Palestrina, Victoria, Josquin, Buxton, Viadana, Tallis, Byrd, and Holst.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Sopranos

Naheed Attari

Sylvia V. Baba

Alexis Wong Baird

Morgan Balfour*

Katelan Bowden*

Arlene Boyd

Olivia T. Brown

Cheryl Cain*

Laura Canavan

Rebecca Capriulo

Sara Chalk

Phoebe Chee*

Andrea Drummond

Tonia D’Amelio*

Katrina Finder

Julia Hall

Elizabeth Heckmann

Axelle Heems

Jocelyn Queen Lambert

Kyounghee Lee

Ellen Leslie*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Bethany R. Procopio

Kelly Ryer

Natalia Salemmo*

Rebecca Shipan

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Sigrid Van Bladel

Zhangguanglu Wang

Lauren Wilbanks

Leilani Zhang

Altos

Carolyn Alexander

Enrica Casucci

Marina Davis*

Valeria D. Estrada Jaime

Shauna Fallihee*

Corty Fengler

Emily (Yixuan) Huang

Hilary Jenson

Gretchen Klein

Katherine M. Lilly

Joyce Lin-Conrad

Madi Lippmann

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Tiffany Ou-Ponticelli

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Sandy Sellin

Meghan Spyker*

Hilary W. Stevenson

Kyle S. Tingzon*

Mayo Tsuzuki

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

Hannah J. Wolf

Tenors

Paul Angelo

Carl A. Boe

Alexander P. Bonner

Todd Bradley

Seth Brenzel*

Dean Christman

Daniel J. Costa

Scott Dickerman

Thomas L. Ellison

Christian Emigh

Sam Faustine*

Patrick Fu

Ron Gallman

Kevin Gibbs*

Michael Jankosky*

Alec Jeong

Drew Kravin

James Lee

Joachim Luis*

David Kurtenbach Rivera*

Grant J. Steinweg

John A. Vlahides

Jack Wilkins*

John Paul Young

Jakob Zwiener

Basses

Simon Barrad*

Ryan Bradford*

Robert Calvert

Sean Casey

Adam Cole*

Noam Cook

James Radcliffe Cowing III

Malcolm Gaines

Richard M. Glendening

Harlan J. Hays*

Vasco Hexel

Bradley A. Irving

Roderick Lowe

Tim Marson

Clayton Moser*

Case Nafziger

Julian Nesbitt

Bradley C. Parese

Timothy Echavez Salaver

Chung-Wai Soong*

Storm K. Staley

Connor Tench

David Varnum*

Julia Vetter

Nick Volkert*

Elliot Yates

Goangshiuan Shawn Ying

Jenny Wong

Chorus Director

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist

*Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists

St. Dominic’s Schola Cantorum

Emilio Peña

Keith Wildenburg

Stephen Staten

Joseph Stillwell

Tatz Ishimaru

Vicente Alvarez

Harry Whitney

Tony DeLousia

Hugo Mendel

Cullen Lauper

Nishad Francis

Julio Martinez

Philip Buonadonna

Simon Berry

Director

The Very Rev. Dr. Malcolm Clemens Young is an Episcopal priest and the Dean of Grace Cathedral, where he oversees the spiritual life of the cathedral and ministers to the cathedral’s congregation and wider community. Young is the moderator of The Forum, the cathedral’s flagship lecture series. He created the Innovative Ministries program and The Vine, a contemporary worship service and community for people ages 20–45. He has also launched programs to expand the cathedral’s social justice programs and digital offerings. Ordained in 1995, Young holds a BA in economics from UC Berkeley and a master of divinity and doctorate of theology from Harvard University. He is the author of The Spiritual Journal of Henry David Thoreau and The Invisible Hand in Wilderness: Economics, Ecology, and God.