In This Program

The Concert

Wednesday, February 25, 2026, at 7:30pm

Mao Fujita piano

Ludwig van Beethoven

Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Opus 2, no.1 (1795)

Allegro

Adagio

Menuetto: Allegretto

Prestissimo

Richard Wagner

Ein Albumblatt (1861)

Alban Berg

Twelve Variations on an Original Theme (1908)

Johannes Brahms

Piano Sonata No. 1, Opus 1 (1853)

Allegro

Andante

Scherzo. Allegro molto e con fuoco–Piu mosso

Finale. Allegro con fuoco

Richard Wagner

(trans. Franz Liszt)

Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde (1859/67)

This concert is performed without intermission.

Program Notes

Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Opus 2, no.1

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1795

It’s one of the most durable plot lines in the book: talented young hopeful arrives in the big city from the hinterlands, filled with energy and promise and a burning desire to make good. After a lucky break, said young hopeful goes on to fame, riches, triumph, and maybe tragedy. Whether it’s Janet Gaynor in A Star is Born or Ruby Keeler in 42nd Street, we all love the story of the kid who goes out there a chorus girl and comes back a star.

In 1792 the kid was Ludwig van Beethoven as he arrived in Vienna from provincial Bonn, armed with some letters of introduction and an agreement to study with Joseph Haydn. He was out to make his mark in the world as both pianist and composer, and to that end he produced a bevy of pieces that thrilled the glitterati. Among those we find a set of three piano sonatas, published in 1796 as his Opus 2 and dedicated to his teacher Haydn. They’re not actually his first piano sonatas, having been preceded by three from his adolescent years. Those Elector sonatas have never quite achieved canonical status, so Opus 2, no.1, is generally credited as the kickoff to the series of 32 piano sonatas that are universally acknowledged as irreplaceable monuments of keyboard literature.

Two centuries of musical evolution have dulled the impact of this sonata’s nervy radicalism. Beethoven’s choice of the rarely- encountered key of F minor was provocative if not downright incendiary, but it’s a key that would come to bear significant emotional weight for him—consider the Appassionata piano sonata and the fiery Opus 95 string quartet. The rocket-like figure that opens the first movement is followed by a tautly reasoned structure that channels Haydn at his most technically sophisticated, but with a punch that is all Beethoven.

The winsome Adagio is cast in a variant of Classical sonata form that omits the central development section. Drawn from his 1785 Piano Quartet No. 3 in C major, it’s considered Beethoven’s earliest piece in the repertory.

After a relatively conventional third movement—a Menuetto and Trio in Sunday-best Viennese Classical style—Beethoven launches into a virtuoso finale characterized by sizzling left-hand triplets and a theme made of etched chords, leading to a brillante and borderline abrupt ending.

Ein Albumblatt

Richard Wagner

Born: May 22, 1813, in Leipzig

Died: February 13, 1883, in Venice

Work Composed: 1861

He was in no way anything even approaching a good piano composer. But Richard Wagner could come up with the occasional effective pianistic trifle, as is the case with this “album leaf” dedicated to Princess Pauline Clémentine von Metternich. A famed socialite and one of Wagner’s most ardent supporters, she moved a few political mountains to bring the opera Tannhäuser to Paris, where it flopped. Although Wagner wasn’t one for spontaneous expressions of gratitude, he nonetheless offered this lovely 1861 piece to her as a heartfelt thank-you note for her efforts on his behalf, however unsuccessful they might have been.

Twelve Variations on an Original Theme

Alban Berg

Born: February 9, 1885, in Vienna

Died: December 24, 1935, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1908

As of November 1908, the Alban Berg of Wozzeck, Lulu, and the Lyric Suite hadn’t been invented yet. He was a student of Arnold Schoenberg, a teacher of rare wisdom who understood that young composers must write through their influences before developing their own individual voices. To that end, Schoenberg set Berg the task of writing a set of variations on an original tune, emphasizing the need to restrict himself to materials extracted from the theme itself, a technique known as “developing variation,” found in composers ranging from Bach to Brahms and destined to serve as a bedrock method for the emerging Second Viennese School. Given the pedagogical purpose behind the variations, neither Schoenberg nor Berg would have been concerned about the genre’s Achilles heel—a deadly predictability that can arise with all those repetitions of the tune, however sliced, diced, jiggered, or juggled they might be.

In these modest variations we can discern the influences of both Mendelssohn (the Variations serieuses) and Schumann (the Symphonic Etudes). Brahms makes an unmistakable appearance in Variation IV, which appears to channel the Intermezzo in E minor, Opus 119, no.2, while the “endless canon” of Variation VI partakes of more than a whiff of Wagner in its fluid chromaticism. The Variations aren’t particularly challenging pianistically, but their upright clarity requires playing of taste and discernment.

The Variations are very much the work of a composer in progress, but the end of Berg’s apprenticeship was nigh. He began his Piano Sonata, Opus 1, that same year. Published in 1910, the sonata marked his arrival into compositional maturity as “among the most auspicious Opus Ones ever written,” according to legendary pianist Glenn Gould.

Piano Sonata No. 1, Opus 1

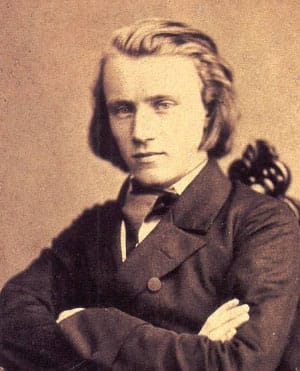

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1853

Robert Schumann’s diary entry for October 1, 1853 reads: “Visit from Brahms; a genius.” In those simple words we witness the first moments of a transformative relationship. The Schumanns were living in Düsseldorf, where Robert’s music directorship of the local orchestra was going downhill fast. The dazzlingly gifted young Brahms must have brought considerable cheer to such depressing circumstances, and before long the Schumann clan had welcomed him as extended family. Robert lost no time in trumpeting his discovery in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. “Fated to give us the ideal expression of the times,” he gushed, describing his new protégé as “a young blood at whose cradle graces and heroes mounted guard.”

Clara was if anything even more swept away. “Here again is one of those who comes as if sent straight from God,” she confided to her diary. “He played us sonatas, scherzos, etc. of his own, all of them showing exuberant imagination, depth of feeling, and mastery of form. Robert says there was nothing he could tell him to take away or add. It is really moving to see him sitting at the piano, with his interesting young face which becomes transfigured when he plays, his beautiful hands, which overcome the greatest difficulties with perfect ease (these things are very difficult), and in addition these remarkable compositions.”

It probably didn’t hurt any that Brahms at age 20 was “handsome as a picture, with long blonde hair,” according to the Schumann’s youngest daughter Marie. That image is difficult to reconcile with the Brahms of popular memory, the portly lifelong bachelor dripping cigar ashes down his unkempt beard, the bonafide grump who once left a party offering an apology to anyone he had managed not to offend. But that was later. For now, Brahms was Robert and Clara’s very own shining Galahad, and their life stories would thereafter remain intertwined with his.

The voice of a young champion rings out clearly throughout Opus 1, which Brahms played for the Schumanns at that memorable first meeting. The influence of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier and Waldstein sonatas is palpable, but there’s nothing particularly derivative on hand. The outer movements are motivically connected by primary themes that outline five notes—four ascending and the last falling; the kinship falls far short of the intensive “developing variation” technique that would come to characterize Brahms’s mature style, but to encounter an embryonic version of it so early in his output bears witness to his lifelong musical integrity.

The opening Allegro is cast in an extended sonata form while the Allegro con fuoco finale is an expertly structured rondo. The inner movements share a subtle join. The slow movement’s variations on a German folk song end with a coda that gently prefigures the following Allegro molto e con fuoco, an early instance of a signature Brahms scherzo in which stormy passages flank an interlude of noble expressivity.

It’s not perfect. The piano writing tends to be blocky and charm is in short supply. It’s not even Brahms’s first piano sonata—only the first one published. But allowing for those caveats, it stands as a profoundly impressive Opus 1 and the dignified inception of a matchless keyboard legacy.

Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde

Richard Wagner

(trans. Franz Liszt)

Work Composed: 1859 (trans. 1867)

There had never been anything quite like Tristan und Isolde. To be sure, there had been any number of operas about illicit lovers, operas in which one or both of the leads were dead as the curtain falls, operas filled with ecstatic love music and heart-rending laments, operas with plots set in motion by some minor or silly contrivance. Tristan includes all of those stock elements. It’s not the plot that was so radical, so daring, and for many, so downright shocking—although some found its unbuttoned sensuality unnerving.

The music was the real bombshell. In seeking an appropriately unsettled and erotically charged idiom for his opera, Wagner had stretched Western tonality past what many considered to be its breaking point. The fundamental principle underlying classical harmony is that of dissonance resolving to consonance—i.e., sonorities that clash leading to those that blend. But here there was no easy resolution, no breath-in, breath-out rhythm of tension-release. It was all increasing tension, as sharp dissonances gave way to weaker ones, the whole avoiding clear resolution for as long as possible. The conservative critic Eduard Hanslick couldn’t stand it. For him, Tristan’s Prelude reminded him of “the old Italian paintings of a martyr whose intestines are slowly unwound from his body onto a reel.” Hector Berlioz was flummoxed by it. Giuseppe Verdi was utterly blown away by it. Clara Schumann detested it. Mark Twain couldn’t fathom what all the fuss was about.

It sounds unbelievable in hindsight, but Wagner originally conceived of Tristan as a quick and easy moneymaker. He wrote his future father-in-law, Franz Liszt, that he meant to create an opera “on a moderate scale, which will make its performance easier” and that would “quickly bring me a good income and keep me afloat for a time.” But such was not to be: Tristan und Isolde wound up complex, lengthy, and brutally demanding of its performers. Not to mention utterly enthralling. “I find it more and more difficult to understand how I could have done such a thing,” Wagner wrote later.

Isolde’s “love-death” over Tristan’s dead body at the opera’s conclusion is no mere lament, but a full-on transfiguration of the spirit, an ultimate release from the pain of existence into a wondrous realm. The Liebestod (and the opera) ends as it must, on a magical major chord that provides that final and long-delayed resolution, whether heard in its original orchestral guise or in Franz Liszt’s stunningly effective transcription for solo piano.

—Scott Foglesong

About the Artist

Mao Fujita

Born in Tokyo, Mao Fujita was still studying at the Tokyo College of Music in 2017 when he took First Prize at Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil in Switzerland, along with the Audience Award, Prix Modern Times, and the Prix Coup de Coeur. He was also the Silver Medalist at the 2019 Tchaikovsky Competition.

This season, Fujita embarks on North American, European, and Asian recital tours, and debuts with the Boston Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Oslo Philharmonic, and Danish National Symphony, among others. He returns to the Czech Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Vienna Symphony, and Deutsches Symphonie Orchester Berlin. In previous seasons, he debuted with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, hr-Sinfonieorchester, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, National Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, NHK Symphony, Yomiuri Nippon Symphony, and Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony. As a chamber musician, he has worked with Renaud Capuçon, Leonidas Kavakos, Emanuel Ax, Kirill Gerstein, Antoine Tamestit, Kian Soltani, and the Hagen Quartet.

After starting piano lessons at the age of three, Fujita won his first international prize in 2010 at the World Classic in Taiwan, and became a laureate of the Rosario Marciano International Piano Competition, Zhuhai International Mozart Competition for Young Musicians, and Gina Bachauer International Young Artists Piano Competition. Fujita is an exclusive Sony Classical International artist and makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this Shenson Spotlight Recital.