In This Program

The Concert

Sunday, January 18, 2026 at 2:00pm

Gunn Theater

California Palace of the Legion of Honor

Alexander Barantschik violin

Peter Wyrick cello

Anton Nel piano

Franz Schubert

Notturno in E-flat major, D.897 (ca. 1827)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Violin Sonata in B-flat major, K.378 (ca. 1779)

Allegro moderato

Andantino sostenuto e cantabile

Rondeau: Allegro

Intermission

Johannes Brahms

Piano Trio No. 1 in B major, Opus 8 (1854/89)

Allegro con brio

Scherzo: Allegro molto

Adagio

Allegro

This series showcases the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin on loan to Alexander Barantschik and the San Francisco Symphony from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Program Notes

Notturno in E-flat major, D.897

Franz Schubert

Born: January 31, 1797, in Vienna

Died: November 19, 1828, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1827

Franz Schubert apparently composed his single-movement Adagio in E-flat major for violin, cello, and piano, in the last year of his life—most likely in October 1827—but it was not published until 1846, when it was headed by the title “Notturno.” He almost certainly planned originally for it to serve as the slow movement of his Piano Trio in B-flat major, D.898, but he replaced it before the trio was unveiled. The longer replacement fits better into the complex scheme of that work, but the original Adagio continued in an independent life.

The Adagio/Notturno has encountered some bad press through the years, dismissed by various writers as “justly neglected,” “unfortunately long-winded,” and “flaccid.” The objections mystify.

Of course Schubert is sometimes a rhapsodic composer, and tight structures are rarely the point of his compositions. But a slow movement that lasts eight minutes (as the Notturno does) can hardly be taken to task for inordinate rambling, especially when it encapsulates such sublime material as this one does. Once heard, Schubert’s Notturno is not soon forgotten.

Strummed chords on the piano introduce a statement of the soft, elegiac theme played by the two string instruments; the forces immediately trade places for the piano to repeat the theme against a pizzicato accompaniment by the strings. Time seems to stand still for the first two minutes of the piece, and then the spell is interrupted by a vigorous variation, replete with rather haughty arpeggios in the piano. This winds down into a searching chromatic passage, which in turn leads to a second variation; now the principal theme is embellished only lightly by a less effusive piano. Schubert further investigates these aspects of the movement’s personality—the elegiac, the stentorian, the “well integrated,” and the questing—until the piece fades away beneath the piano’s gentle trills and ascending arpeggios.

Violin Sonata in B-flat major, K.378

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born: January 27, 1756, in Salzburg

Died: December 5, 1791, in Vienna

Work Composed: ca. 1779

Though acknowledged as one of the finest keyboard virtuosos of his day, Mozart was also a very accomplished performer on violin and viola. He therefore was perfectly positioned to champion the “sonata for pianoforte with violin accompaniment,” as the genre was typically identified when it emerged in the second half of the 18th century. As that wording suggests, the piano was generally the dominant partner in these works; indeed, there are many such pieces that could be conveyed adequately if played without the violin part, which might be limited to offering pleasant but dispensable echoes.

That was the case with the earliest of Mozart’s 33 violin- and-keyboard sonatas, his first 10 dating from no later than 1764, when he turned eight, although the sonatas of his maturity explore how the two instruments can work together in a more enriching way. The dates of Mozart’s violin sonatas span the time when the harpsichord was ceding its place to the piano; indeed, his manuscript for this piece labels the keyboard part “cembalo,” signifying harpsichord. Nonetheless, the part includes many dynamic markings, often momentary, which would have conveyed little if they were played on a harpsichord.

This is one of the pieces Mozart referred to in a letter he wrote to his sister (in Salzburg) on July 4, 1781, from his new home in Vienna: “As regards new compositions for the clavier [keyboard], let me tell you that four sonatas are ready to be engraved: the sonatas in C and B-flat are among them, only the other two are new.” The letter implies that his sister was already familiar with two of these works—they would have been the violin sonatas in C major, K.296, and the elegant one played here—which means that they must have been composed while Mozart was still living at home in Salzburg.

In November 1781, the firm of Artaria & Company published a group of six violin sonatas, including this one, as Mozart’s Opus 2; the composer sent his sister a copy on December 15. This collection was Mozart’s first Viennese publication and it launched his long association with Artaria. The set bears a dedication to Josepha Barbara Auernhammer. She was the daughter of an economic councilor in Vienna, and shortly after Mozart’s arrival in Vienna she signed on as his piano pupil. She had a crush on Mozart, and even fueled rumors that they were going to be engaged, but he did not share those sentiments in the slightest. Once published, the Opus 2 Sonatas made their way around, and an anonymous “Report from Italy,” published in Carl Friedrich Cramer’s Magazin der Musik on July 9, 1784, reads: “Mozart’s sonatas with obbligato violin please me greatly. They are very difficult to play. Admittedly the melodies are not at all new, but the accompaniment of the violin is masterly.” The characterization of Mozart’s instrumental music as inordinately difficult, even insurmountably so, was not unusual at that time, with complaints being particularly vociferous in Italy—ironically, since it was often vaunted as the native soil of great string playing.

Piano Trio No. 1 in B major, Opus 8

Johannes Brahms

Born: May 7, 1833, in Hamburg

Died: April 3, 1897, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1854 (rev. 1889)

In late September 1853, the 20-year-old Johannes Brahms appeared on the Düsseldorf doorstep of Robert and Clara Schumann. They welcomed him warmly, having heard about him from their friend-in-common Joseph Joachim, the violinist. Brahms grew enamored of the couple—of Robert, the acclaimed but volatile composer, conductor, and critic; of Clara, the exceptional pianist, insightful muse, and resilient survivor. They adored him, too, and their friendship deepened instantly, taking on both intellectual and vaguely erotic overtones. A month after their first meeting, Robert published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik an effusive article titled “Neue Bahnen” (New Paths).

The new year found Brahms in Hanover, where he embarked on his B-major piano trio. Distractions soon loomed in his path, the most disconcerting arriving in late February, when Robert leapt off a bridge into the Rhine in the dramatic suicide attempt that would signal the irretrievable crumbling of his sanity. Brahms immediately left for Düsseldorf and did what he could to console Clara, who was five months into her 10th pregnancy. By then, Robert had been removed, at his own request, to an asylum near Bonn, where he would die two and a half years later. Musician-friends gathered to help distract Clara and music inevitably filled the household. One of the pieces that appeared on the music stands was the piano trio that occupied Brahms when he could find time to work on it.

Clara found it perplexing. “I cannot quite get used to the constant change of tempo in his works,” she wrote in her journal, “and he plays them so entirely according to his own fancy that … I could not follow him, and it was very difficult for his fellow-players to keep their places.” But by mid-April the piece had progressed considerably, and after playing it twice through one day she changed her tone: “Now everything in it is clear to me.” She wrote a letter to the firm of Breitkopf & Härtel, which published Robert’s compositions as well as her own, urging them to add Brahms’s new trio to their catalogue, which they did.

But the B-major piano trio published then was effectively superseded when the composer rewrote the piece 37 years later. Brahms spent the summer of 1889 at Bad Ischl, a fashionable vacation hangout for Vienna’s aristocracy and cultural crowd. He wrote to Clara: “With what childish amusement I while away the beautiful summer days you will never guess. I have rewritten my B-major Trio.… It will not be so wild as it was before—but whether it will be better—?”

Apart from the nagging awareness that, with so many years of experience under his belt, he could craft the work’s material into a far more refined piece, there was a practical reason for this revision. Breitkopf & Härtel had sold the rights for Brahms’s first 10 published works to the rival firm of Simrock, which had since become Brahms’s usual publisher. Because Simrock would be printing a new edition anyway, Brahms felt the time was ripe to bring the piece up to his current level of ruthless self-appraisal. He assured Simrock that, in its new guise, the trio would be “shorter, hopefully better, and in any case more expensive.” What is most extraordinary about Brahms’s revision is that he still spoke fluently the musical language of his youth. Certainly he had grown more expert as a composer, and the considerable tightening to which he subjected the piece—the revision is two-thirds the length of the original—is an improvement. Brahms maintained ambivalence about the two versions, and seems to have been perfectly content that both incarnations should be in circulation.

The first movement (Allegro con brio, ramped up from Allegro con moto in the first version) opens with a theme that is warmhearted and stately, growing from deep in the piano into a full-throated effusion for all three instruments, a descendant of the finale tune of Schubert’s Great Symphony, perhaps, and an ancestor of the finale theme from Brahms’s own First Symphony. H.L. Mencken, writing in his capacity as music critic for the Baltimore Sun, declared this theme “the loveliest tune, perhaps, in the whole range of music.” The Scherzo (Allegro molto) and its central trio section remained essentially unaltered when Brahms rewrote the piece, except for the appending of a concise coda in which the strings slip away toward silence. The slow movement, an Adagio (Adagio non troppo in the first version), opens with a hushed, hymn-like melody, a mystical chorale that bears some resemblance to correspondingly serene material in Beethoven’s G-major piano concerto. In the 1854 version, Brahms had worked in an allusion to Schubert’s “Am Meer,” a song about frustrated love; sometimes interpreted as an autobiographical detail referring to Brahms’s feelings for Clara, this reference was eliminated in the revision.

The final Allegro (originally Allegro molto agitato) is in B minor. Although it’s not uncommon for minor-mode compositions to end in the major, the opposite is rare: Haydn’s String Quartet in G major, Opus 76, no.1, and Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony are two examples from the standard repertoire. In fact, the key of Brahms’s principal theme here is ambiguous; this tightly wound subject seems as much drawn in F-sharp minor as in B minor—but minor-mode either way. Brahms’s revision enhanced the subtlety of key relationships within this movement, even introducing a spacious subsidiary theme in D major. Few listeners can hope to immediately grasp the niceties of the structural improvements, but this movement’s mounting passion will be evident to all.

—James M. Keller

About the Artists

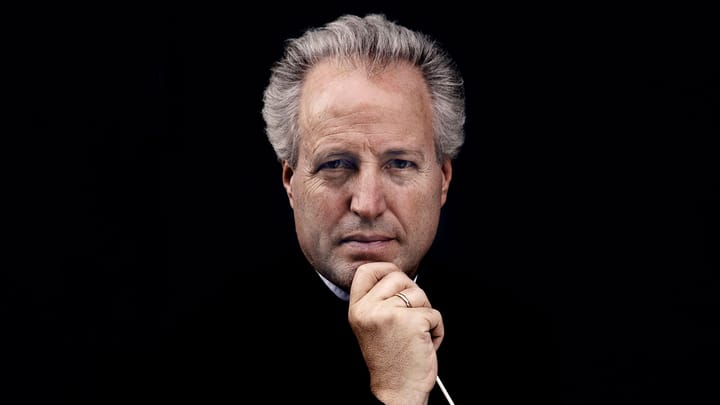

Alexander Barantschik

Alexander Barantschik began his tenure as the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster in September 2001 and holds the Naoum Blinder Chair. He was previously concertmaster of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, and has been an active soloist and chamber musician throughout Europe. He has collaborated in chamber music with André Previn, Antonio Pappano, and Mstislav Rostropovich. As leader of the LSO, Barantschik toured Europe, Japan, and the United States, performed as soloist, and served as concertmaster for major symphonic cycles with Michael Tilson Thomas, Rostropovich, and Bernard Haitink. He was also concertmaster for Pierre Boulez’s year-long, three-continent 75th birthday celebration.

Born in Russia, Barantschik attended the Saint Petersburg Conservatory and went on to perform with the major Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. His awards include first prize in the International Violin Competition in Sion, Switzerland, and in the Russian National Violin Competition. Since joining the SF Symphony, Barantschik has led the Orchestra in several programs and appeared as soloist in concertos and other works by Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Walton, Piazzolla, and Schnittke, among others. Barantschik is a member of the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches graduate students from around the world in a special concertmaster program. Through an arrangement with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Barantschik has the exclusive use of the 1742 Guarneri del Gesù violin once owned by the virtuoso Ferdinand David, who is believed to have played it in the world premiere of the Mendelssohn E-minor Violin Concerto in 1845. It was also the favorite instrument of the legendary Jascha Heifetz, who acquired it in 1922 and who bequeathed it to the Fine Arts Museums, with the stipulation that it be played only by artists worthy of the instrument and its legacy.

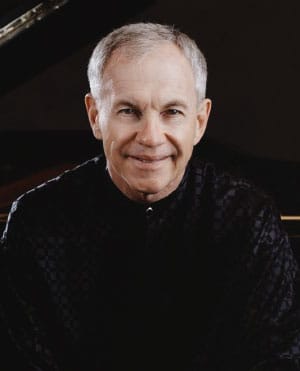

Anton Nel

Winner of the 1987 Naumburg International Piano Competition, Anton Nel tours as a recitalist, concerto soloist, chamber musician, and teacher. Highlights in the United States include performances with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Dallas Symphony, and Seattle Symphony, as well as recitals from coast to coast. He has appeared internationally at Wigmore Hall, the Concertgebouw, Suntory Hall, and major venues in China, Korea, and South Africa.

Nel holds the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Endowed Chair at the University of Texas at Austin, and in the summers is on the faculties of the Aspen Music Festival and School and the Steans Institute at the Ravinia Festival. Born in Johannesburg, Nel is also an avid harpsichordist and fortepianist, and is a graduate of the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied with Adolph Hallis, and the University of Cincinnati, where he worked with Béla Síki and Frank Weinstock. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in 1994.

Peter Wyrick

Peter Wyrick was a member of the San Francisco Symphony cello section from 1986–89, rejoined the Symphony as Associate Principal Cello from 1999–2023, and retired from the Orchestra at the end of the 2023–24 season. He was previously principal cello of the Mostly Mozart Orchestra and associate principal cello of the New York City Opera. He has appeared as soloist with the SF Symphony in works including C.P.E. Bach’s Cello Concerto in A major, Bernstein’s Meditation No. 1 from Mass, Haydn’s Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, and music from Tan Dun’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon Concerto.

In chamber music, Wyrick has collaborated with Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Yefim Bronfman, Lynn Harrell, Jeremy Denk, Julia Fischer, and Edgar Meyer, among others. As a member of the Ridge String Quartet, Wyrick recorded Dvořák’s piano quintets with pianist Rudolf Firkušný on an RCA recording that received the Diapason d’Or and a Grammy nomination. He has also recorded Fauré’s cello sonatas with pianist Earl Wild for dell’Arte records. Born in New York to a musical family, he began studies at the Juilliard School at age eight and made his solo debut at age 12.