In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, January 15, 2026, at 7:30pm

Friday, January 16, 2026, at 7:30pm

Saturday, January 17, 2026, at 7:30pm

Inside Music Talk: “Holst Beyond The Planets”

Kenric Taylor, Founder and Editor of GustavHolst.info, in conversation with Benjamin Pesetsky

On stage at 6:30pm before each performance

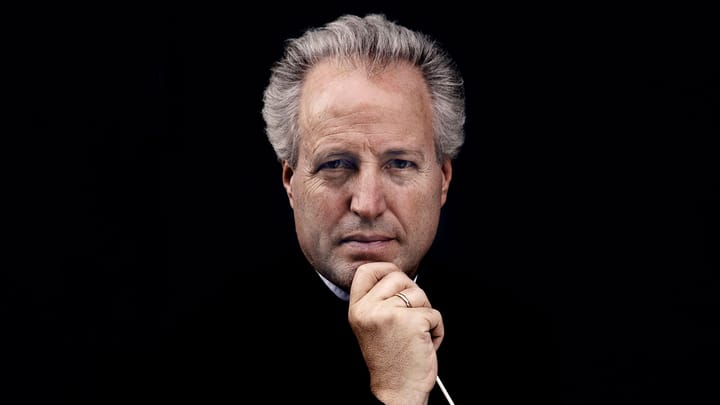

Edward Gardner conducting

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Overture to The Wasps (1909)

First San Francisco Symphony Performances

Max Bruch

Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Opus 26 (1867)

Prelude: Allegro moderato

Adagio

Finale: Allegro energico

Randall Goosby

Intermission

Gustav Holst

The Planets, Opus 32 (1917)

Mars, the Bringer of War

Venus, the Bringer of Peace

Mercury, the Winged Messenger

Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity

Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age

Uranus, the Magician

Neptune, the Mystic

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

Jenny Wong director

Lead support for the San Francisco Symphony Chorus this season is provided through a visionary gift from an anonymous donor.

Inside Music Talks are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

The Planets is by far Gustav Holst’s most famous work, an iconic representation of our solar system and the astrological significance of each planet. The suite’s jolting rhythms, grand tunes, and eerie atmospheres are so recognizable it’s easy to forget how original it was in the late 1910s.

In between, Randall Goosby performs Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1, a violin classic by an otherwise overlooked composer, with Hungarian-spiced licks and crowd-pleasing passagework.

Overture to The Wasps

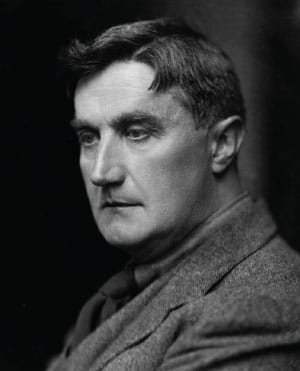

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born: October 12, 1872, in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, England

Died: August 26, 1958, in London

Work Composed: 1909

First SF Symphony Performances

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbal, and bass drum), harp, and strings

Duration: About 9 minutes

Ralph Vaughan Williams’s influence on British music looms large. Marking the composer’s 150th birthday in 2022, Hugh Morris noted in The Guardian that “Vaughan Williams enjoyed a combination of popularity and prestige unrivalled by many of his British contemporaries, and he remains the nation’s favourite composer, even if others might have a stronger claim to be Britain’s best.”

His music, alongside the oeuvres of Edward Elgar and Frank Bridge, lit the way for a new generation of British modernists like Benjamin Britten and William Walton, blending traditional British source material (he was a lifelong cataloguer of folk song and Tudor music) with a lightness influenced by French impressionism.

His milieu, too, was a blend of heavyweight British tradition and an enterprising progressivism. Born to a reverend father in a wealthy family boasting connections in both the church and the law, Vaughan Williams attended the Royal College of Music and Trinity College Cambridge. However, his family’s progressive views set him apart from religious and societal orthodoxies (he identified as agnostic and was the great-nephew of Charles Darwin).

His studies included tutelage under Charles Stanford and Hubert Parry, a collaborative relationship with fellow student Gustav Holst, and a brief stint on his honeymoon learning from Max Bruch. But the two most formative events of his compositional career would not occur until his 30s. After beginning his ethnographic work with folk and Tudor music in 1903, he composed his first works incorporating these materials—unlike composers with extensively performed juvenilia, Vaughan Williams’s programmed works all follow this shift in approach. Seeking further refinement of this new voice, he completed three months of study a few years later with Maurice Ravel, though he was several years Ravel’s elder. According to musicologist Roger Nichols, Ravel helped Vaughan Williams shed a “heavy contrapuntal Teutonic manner.”

In the intervening years between his return and the outbreak of World War I, Vaughan Williams composed some of his most well-known works (Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, The Lark Ascending). After a brief artillery service in the war, he returned to teaching and composition, continuing to write (largely symphonic works and songs) and lecture until his 1958 passing.

The Music

This overture was composed as part of incidental music for the Cambridge Greek Play’s 1909 production of Aristophanes’s The Wasps, a fifth-century BCE satire of the Athenian legal system. Vaughan Williams, himself a graduate of Cambridge, had recently returned from his two-year spell in France.

The overture opens with trills across the orchestra’s strings, a queasy buzzing that erupts in brief, swerving flights. A remarkably chromatic, French-inflected swell opens into a charming, storybook melody led by a gregarious dotted motif.

Lyrical questions asked by a solo horn and violin are answered with the dotted motif (in the oboe and clarinet, respectively). The interrogative feeling resolves with a soaring, unison melody over a sweeping, arpeggiated harp. But again, a pervasive uneasiness returns. A more articulate harp prods wandering winds as Ravel’s harmonic influence pokes through once more.

As the music recedes into uncertainty, the emphatic return of the trilling texture announces the piece’s final section. The returning dotted motif builds towards the overlapping reemergences of the opening section’s melodies, punctuated by the swerving scales of the introduction magnified in the winds and harp. Outlining the main melody in half-time, the ensemble picks up pace to end the overture in a triumphant flash.

—Lev Mamuya

Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Opus 26

Max Bruch

Born: January 6, 1838, in Cologne

Died: October 2, 1920, in Berlin

Work Composed: 1865–67

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1913. Henry Hadley conducted with Maude Powell as soloist. Most recent—May 2019. Marek Janowski conducted with James Ehnes as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 24 minutes

Max Bruch was born during an era of seismic changes in the dominant idioms of German art music. A staunch champion of the sound defined by Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann, “he stayed behind to defend the bastion of mid-nineteenth-century Romanticism,” writes biographer Chirstopher Fifield, “[and] thus became an increasingly isolated figure and an equally embittered one.”

Despite a six-decade career as a composer, Bruch’s conservatism put him out of sync with the period’s innovations. As musicologist Georg Predota puts it, “He emerged on the German music scene dominated by Mendelssohn, lived under the shadow of Wagner and Brahms, and died within a decade of the first performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire.”

Born in Cologne to a musical family (his mother was a singer), Bruch began composing at a young age, studying in both his hometown and nearby Bonn. After early-career stints in Mannheim, Paris, and Brussels, Bruch began to balance his compositional output with conductorial appointments—he wrote the Violin Concerto No. 1 during a stint as music director of the court of Koblenz.

A brief term as music director of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society was marred by contentious relationships with its governing committee and a lack of time to devote towards composition (though both his Scottish Fantasy and Kol Nidrei were completed and premiered during this time). After escaping to a new post in Breslau, Bruch eventually arrived in Berlin, where he devoted himself to his new family (he married soprano Clara Tuczek in 1881 during his time in Liverpool), his teaching at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (students included a young Ottorino Respighi), and continued composition until his death in 1920.

The Music

“The Germans have four violin concertos … the richest, the most seductive was written by Max Bruch,” said Joseph Joachim, arguably the most important violinist of the 19th century. Despite the other three concerto-writers’ greater contemporary renown (Beethoven, Brahms, and Mendelssohn), Bruch’s First Violin Concerto stands (along with his Scottish Fantasy, another work for solo violin and orchestra) as one of his most enduring works and a standard of the violin’s concerto repertoire. Joachim helped Bruch revise the concerto, and premiered the final version in 1867.

In the first movement—an allegro in sonata form—the violin answers two quiet, chorale-like interrogatives from the winds with brief, wandering fantasias. A third, louder statement of the chorale launches the solo violin into the movement’s first theme, full of bravura and sorrow in equal measure.

The second theme—lyrical and thick with sentiment—sees the violin alternately in the rich depths of its range and in its upper limits. A brief return of the first theme’s material in the dominant major quickly devolves into a pyrotechnic development, one which leads into a thundering tutti (a full orchestra passage).

The chorale figure from the opening emerges declaratively—snarling and diminished in the thundering brass—before receding towards the recapitulation. The violin’s fantasy intensifies towards a final orchestral interlude, which starts strongly before falling, attacca (without pause), into the second movement’s opening melody (a sweet, lullaby-like tune).

Out of simple building blocks—the initial melody and an additional dotted motif—Bruch builds titanic ebbs and flows. They bloom with pastoral beauty, glow quietly, and thunder forward in tutti—all connected by the violin’s alternating lyricism and filigree. The soloist’s final, tender statement of the theme swells—then falls again.

The third movement’s suppressed strings quickly roar to life and set up the violin’s entrance with the finale’s swashbuckling theme, one which is then echoed by the orchestra. A run of winding triplets leads the ensemble towards a triumphant statement of the second, more sustained theme.

After offering a calmer, more assured restatement in the solo line, the toggling between the two thematic groups continues, all linked by virtuosic stretches in the solo line. The violin’s final transformations of the first theme give way to a galloping presto which ends the concerto.

—L.M.

The Planets, Opus 32

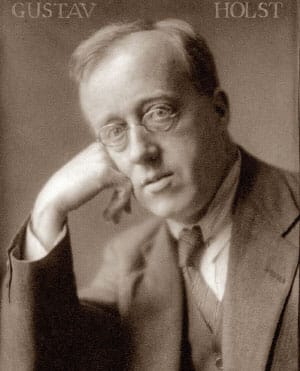

Gustav Holst

Born: September 21, 1874, in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England

Died: May 25, 1934, in London

Work Composed: 1914–16

SF Symphony Performances: First—November 1929. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—October 2023. Elim Chan conducted.

Instrumentation: 4 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo and 4th doubling alto flute and piccolo), 3 oboes (3rd doubling bass oboe), English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 6 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tenor tuba, tuba, timpani (2 players), percussion (triangle, tambourine, cymbals, gong, snare drum, bass drum, orchestra bells, glockenspiel, and xylophone), 2 harps, celesta, organ, and strings. “Neptune” adds a wordless chorus of sopranos and altos.

Duration: About 50 minutes

Though Gustav Holst’s The Planets is a foundational piece of space music—a sonic accompaniment for children learning about the solar system and an inspiration for sci-fi scores from The Twilight Zone to Star Trek to Star Wars—the piece was inspired less by astronomy than by astrology. The composer was a bit embarrassed by his interest in this pseudoscience, which he learned about in 1913 while vacationing in Spain. He professed not to take it seriously as fortunetelling, but admitted to a fascination with human personalities and how they might be affected by celestial bodies. The movements’ subtitles—“The Bringer of War,” “The Bringer of Peace,” “The Bringer of Jollity,” and so forth—suggest earthly affairs as much as anything beyond our orbit.

As a young man in 1895, Holst earned a scholarship to the Royal Conservatory of Music, and then worked as a trombonist in theater orchestras. But he soon gave that up to become a teacher at the James Allen’s Girls’ School and musical director at St. Paul’s Girls’ School, both in London. By all accounts he was an excellent teacher who took seriously the musical talents of young women. His students participated in many of his pieces and were sometimes entrusted with preparing scores and sheet music, especially when bouts of inflammation prevented him from writing things out by hand.

Though respected as an educator, Holst had found only limited recognition as a composer as he neared 40. This didn’t necessarily bother him—he detested publicity and was content with small and semi-private performances. Imogen Holst, his daughter and biographer, paraphrased his outlook: “A piece of music was either good or bad. If it was good it would speak for itself. Why dress it up in headlines, and concoct little paragraphs about it for the gossip columns of the evening papers?”

Yet in 1911 he made a New Year’s resolution to be more ambitious. He had already written a number of choral and orchestral works, some inspired by English folksong and others by Sanskrit texts and Hindu philosophy. Soon he began to conceive a new kind of orchestral suite with the working title “Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra”—what we now know as The Planets. The very concept of a nearly hour-long, seven-movement orchestral suite had few precedents—symphonic in scope, but not at all a symphony in form. Holst’s sense of orchestration and harmony was rooted in the music of Richard Wagner and Claude Debussy, but at times even bolder and farther out. “Even those listeners who had studied the score for months were taken aback by the unexpected clamour of Mars,” reported Imogen.

It took Holst almost four years to finish the piece—composing in his soundproof music room at St. Paul’s on weekends and school vacations—and then he waited another three for a complete performance, in 1920. Early previews were limited to just a few movements because the conductor Adrian Boult thought “when [listeners] are being given a totally new language like that, 30 minutes of it is as much as they can take in.” But he underestimated his audience—the piece quickly became extremely popular, and Holst achieved a level of celebrity he almost instantly regretted. “Gushing admirers were the plague of his life,” recalled Imogen. “His ‘enemies’—those who hated his music with a hatred that seemed almost personal in its intensity—he could easily ignore, but the adoration of some of his disciples could be painfully embarrassing.”

The Music

It was important to Holst to differentiate the musical symbolism of The Planets from the kind of epic musical storytelling found in the tone poems of Richard Strauss. “These pieces were suggested by the astrological significance of the planets; there is no programme music,” he wrote. “Neither have they any connection with the deities of classical mythology bearing the same names. If any guide to the music is required, the subtitle to each piece will be found sufficient, especially if it be used in the broad sense. For instance, Jupiter brings jollity in the ordinary sense, and also the more ceremonial type of rejoicing associated with religions or national festivities. Saturn brings not only physical decay, but also a vision of fulfillment. Mercury is the symbol of mind.”

Holst didn’t think it necessary to say anything more, but here is a slightly more elaborate guide to the music:

Mars, the Bringer of War, was completed just before the outbreak of World War I, as if Holst could foresee the conflict. Its driving, off-kilter march ends in a fractured climax. Venus, the Bringer of Peace, was written as the first news came of combat on the Western Front. It is a lyrical and melancholy movement with horns and winds mingling with hushed strings.

Mercury, the Winged Messenger, is rambunctious and fleeting, with silvery touches from the harp and celesta. Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity, was heavily influenced by English folksong, broadening in the second half with a plummy strings-and-brass theme marked Andante maestoso (majestic).

Now we gaze to the outer solar system, encountering stranger, more distant planets. Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age, is a creaky giant, wheezy and weary, but still an eminent presence when roused. Uranus, the Magician, has a whole bag of tricks—entertaining and eccentric, wobbling between frightening and just-kidding.

At last, Neptune, the Mystic, is cold and remote. “The strange chords in Neptune make our ‘moderns’ sound like milk and water,” wrote Ralph Vaughan Williams in a forward for Holst’s biography. “Yet these chords never seem ‘wrong’, nor are they incongruous.” Here Holst introduces an offstage chorus of sopranos and altos, sung at the first performance by his own students. The most human sound in the entire piece is also the most unearthly, with the last bar repeated until the sound is lost in the distance.

—Benjamin Pesetsky

A version of this note previously appeared in the program book of the St. Louis Symphony.

Kenric Taylor is the founder and editor of the music resource site GustavHolst.info. He currently performs as a bass chorister with Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra & Chorale and has previously sung with the San Francisco Opera Chorus, International Orange Chorale of San Francisco, and San Francisco Boys Chorus. A graduate of Williams College, he is active in arts leadership as a board member for New Amsterdam Records, and works professionally at Google.

Benjamin Pesetsky is Associate Director of Editorial and curates Inside Music Talks for the San Francisco Symphony. He has also written program notes for the St. Louis Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra, and recently wrote liner notes for the Melbourne Symphony’s recording of The Planets in partnership with the London Symphony’s LSO Live label.

About the Artists

Edward Gardner

Edward Gardner is principal conductor of the London Philharmonic and music director of the Norwegian Opera and Ballet, with whom he will lead a complete Ring cycle in 2028–29. He additionally serves as honorary conductor of the Bergen Philharmonic, following his tenure as chief conductor from 2015–24. During his fifth season with the LPO, Gardner tours South Korea and Germany.

This season, Gardner returns to the Chicago Symphony, National Symphony, and Dallas Symphony, and debuts with Pittsburgh Symphony. In Europe, he conducts Berlin Radio Orchestra, WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Danish National Symphony, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. In Tokyo, he makes his debut with Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra. Last summer he returned to Bavarian State Opera for Rusalka, following his debut with Peter Grimes in 2022 and Otello in 2023, and will conduct several productions there in coming seasons. In summer 2026 he will lead a new production of Suor Angelica and La mort de Cléopâtre at the Tiroler Festspiele Erl.

Previously music director of English National Opera from 2007–15, Gardner has also built a strong relationship with the Metropolitan Opera with productions of Damnation of Faust, Carmen, Don Giovanni, Der Rosenkavalier, and Werther. Elsewhere, he has conducted at La Scala, Chicago Lyric Opera, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, and Opéra National de Paris. Other appearances in recent seasons include the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Berlin Staatskapelle, Vienna Symphony, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala. He also has had longstanding collaborations with the City of Birmingham Symphony, where he was principal guest conductor from 2010–16, and the BBC Symphony, whom he has conducted at both the First and Last Night of the BBC Proms. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in March 2018.

Randall Goosby

Randall Goosby debuts this season with the Atlanta Symphony, Orchestre National de France, San Diego Symphony, Memphis Symphony, and Portland Symphony. He also returns to the Pittsburgh Symphony and New Jersey Symphony, and joins the Sphinx Virtuosi on their US tour this spring. Previous engagements include debuts with the Chicago Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, Montreal Symphony, and Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. He joined the London Philharmonic and Edward Gardner on their 2024 US tour. He made his debut at the San Francisco Symphony with a Shenson Spotlight Recital in April 2022, and made his concerto debut with the Orchestra the following September.

Signed exclusively to Decca Classics in 2020 at the age of 24, Goosby’s debut concerto album was released in 2023 with the Philadelphia Orchestra, including concertos by Max Bruch and Florence Price. His first Decca album, Roots, is a celebration of African American music, exploring its evolution from the spiritual to present-day compositions. He released Roots: Deluxe Edition in 2024.

Goosby is deeply passionate about inspiring and serving others through education, social engagement, and outreach activities. He has enjoyed working with nonprofit organizations such as the Opportunity Music Project and Concerts in Motion in New York City, as well as performing at schools, hospitals, and assisted living facilities across the United States.

In 2018, Goosby won first prize in the Young Concert Artists International Auditions, and in 2010 won first prize in the Sphinx Concerto Competition. He is also a recipient of Sphinx’s Isaac Stern Award, a career advancement grant from the Bagby Foundation, and a 2022 Avery Fisher Career Grant. He debuted with the New York Philharmonic on a Young People’s Concert at age 13. He studied at the Juilliard School with Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho, and recently joined Juilliard’s Pre-College violin faculty. He plays the Antonio Stradivari “ex-Strauss” violin from 1708, on generous loan from Samsung Foundation of Culture.

Jenny Wong

Jenny Wong is Chorus Director of the San Francisco Symphony, as well as the associate artistic director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale. Recent conducting engagements include the Los Angeles Philharmonic Green Umbrella Series, Los Angeles Opera Orchestra, the Industry, Long Beach Opera, Pasadena Symphony and Pops, Phoenix Chorale, and Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles.

Under Wong’s baton, the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s performance of Frank Martin’s Mass was named by Alex Ross one of ten “Notable Performances and Recordings of 2022” in the New Yorker. In 2021 she was a national recipient of Opera America’s inaugural Opera Grants for Women Stage Directors and Conductors. She has conducted Peter Sellars’s staging of Orlando di Lasso’s Lagrime di San Pietro, Sweet Land by Du Yun and Raven Chacon, and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar with Long Beach Opera in collaboration with WildUp. She has prepared choruses for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8 that won a 2022 Grammy Award for Best Choral Performance.

A native of Hong Kong, Wong received her doctor of musical arts and master of music degrees from the University of Southern California and her undergraduate degree in voice performance from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She won two consecutive world champion titles at the World Choir Games 2010 and the International Johannes Brahms Choral Competition 2011. She recently extended her contract with the SF Symphony through the 2028–29 season.

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

The San Francisco Symphony Chorus was established in 1973 at the request of Seiji Ozawa, then the Symphony’s Music Director. The Chorus, numbering 32 professional and more than 120 volunteer members, now performs more than 26 concerts each season. Louis Magor served as the Chorus’s director during its first decade. In 1982 Margaret Hillis assumed the ensemble’s leadership, and the following year Vance George was named Chorus Director, serving through 2005–06. Ragnar Bohlin concluded his tenure as Chorus Director in 2021, a post he had held since 2007. Jenny Wong was named Chorus Director in September 2023.

The Chorus can be heard on many acclaimed San Francisco Symphony recordings and has received Grammy Awards for Best Performance of a Choral Work (for Orff’s Carmina burana, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 8) and Best Classical Album (for a Stravinsky collection and for Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Symphony No. 8).

San Francisco Symphony Chorus

SOPRANOS

Elaine Abigail

Adeliz Araiza

Naheed Attari

Alexis Wong Baird

Morgan Balfour*

Helen J. Burns

Cheryl Cain*

Laura Canavan

Sarita Nyasha Cannon

Rebecca Capriulo

Sara Chalk

Phoebe Chee*

Andrea Drummond

Tonia D’Amelio*

Elizabeth Emigh

Katrina Finder

Cara Gabrielson*

Tiffany Gao

Susanna Gilbert

Julia Hall

Elizabeth Heckmann

Axelle Heems

Kate Juliana

Jocelyn Queen Lambert

Ellen Leslie*

Caroline Meinhardt

Jennifer Mitchell*

Ria Patel

Laura Prichard

Bethany R. Procopio

Hallie Randel

Natalia Salemmo*

Rebecca Shipan

Elizabeth L. Susskind

Zhangguanglu Wang

Lauren Wilbanks

ALTOS

Carolyn Alexander

Melissa Butcher

Marina Davis*

Erica Dunkle*

Valeria D. Estrada Jaime

Emily (Yixuan) Huang

Kelsey M. Ishimatsu Jacobson

Hilary Jenson

Cathleen Josaitis

Joyce Lin-Conrad

Madi Lippmann

Margaret (Peg) Lisi*

Brielle Marina Neilson*

Kimberly J. Orbik

Leandra Ramm*

Celeste Riepe

Jeanne Schoch

Kathryn Schumacher

Yuri Sebata-Dempster

Meghan Spyker*

Hilary W. Stevenson

Mayo Tsuzuki

Makiko Ueda

Merilyn Telle Vaughn*

Heidi L. Waterman*

*Member of the American Guild of Musical Artists

Jenny Wong

Chorus Director

John Wilson

Rehearsal Accompanist