In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, October 16, 2025, at 2:00pm

Friday, October 17, 2025, at 7:30pm

Saturday, October 18, 2025, at 7:30pm

Postconcert Conversation with Sarah Cahill

On stage Thursday immediately following the matinee performance

Preconcert Conversation with Members of the SF Symphony

On stage Friday and Saturday at 6:30pm

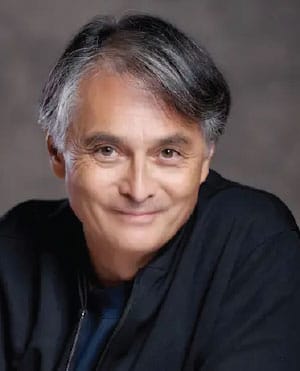

Jun Märkl conducting

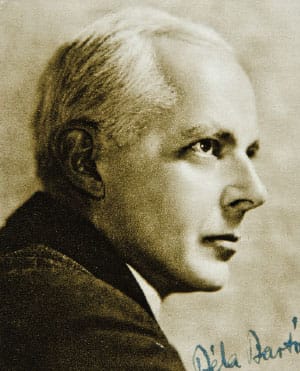

Béla Bartók

Violin Concerto No. 2 (1938)

Allegro non troppo

Andante tranquillo

Allegro molto

Leonidas Kavakos

Intermission

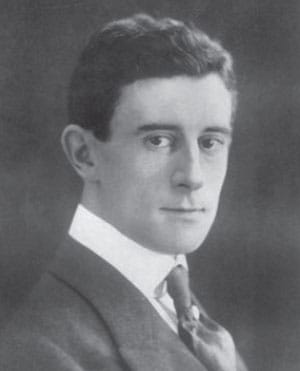

Maurice Ravel

Daphnis et Chloé (1912)

Part I

Introduction et Danse religieuse

Danse générale

Danse grotesque de Dorcon

Danse légère et gracieuse de Daphnis

Danse de Lycéion

Danse lente et mystérieuse des Nymphes

Part II

Introduction

Danse guerrière

Danse suppliante de Chloé

Part III

Lever du jour

Pantomime (Les amours de Pan et Syrinx)

Danse générale (Bacchanale)

Thursday matinee concerts are endowed by a gift in memory of Rhoda Goldman.

Preconcert talks and postconcert conversations are supported in memory of Horacio Rodriguez.

Program Notes

At a Glance

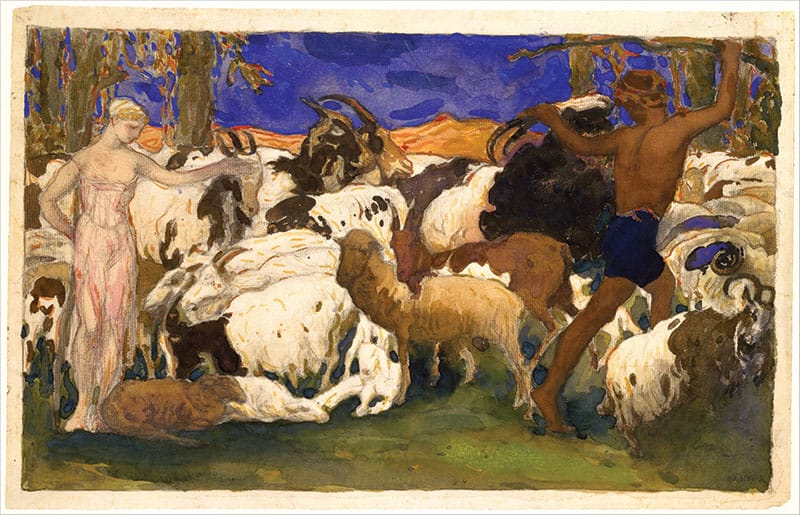

On the second half is Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé, which he wrote for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris. The plot is based on a Greek myth, projected through a painterly Belle Époque lens. It tells a coming-of-age story as the adolescent foundlings Daphnis and Chloé fall in love after a series of trials involving pirates, nymphs, and the intercession of the god Pan.

Ravel and Bartók: Music in the Shadow of War

“More is more.” In many ways, this was the guiding principle of European music in the late 19th century. In the hands of German composers like Gustav Mahler and Richard Wagner, musical works were getting longer and more complex, and required ever-larger orchestras (which meant that music was getting louder, too). Emotional expression was reaching fever pitch. But music wasn’t getting bigger along every dimension just because it could. The “maximalist” German composers were convinced that there were great metaphysical questions that could only be grappled with through music: What is the fundamental nature of reality? What is the point of suffering? Why are we here at all? And music needed to grow in order to assume its weighty vocation. Only then could it offer deliverance from ignorance, and affirm the triumph of the human spirit.

But by the early 20th century, this was all beginning to seem a bit dubious. Political upheaval across Europe was redirecting attention from the metaphysical to the decidedly earthly. The question of national identity was increasingly urgent and contested: in this context, the world-transcending aspirations of the late Romantic composers seemed rather obtuse. And the unimaginable horror that was unleashed following the outbreak of World War I in 1914 cast German paeans to the conquering human spirit in a dim light. Young soldiers were ripped apart by machine guns; cities were bombed by fearsome Zeppelins; fields were churned into mud and gore. That Germany should continue to be the standard-bearer for European music was beginning to seem intolerable to many. Having long been respected as the arbiter of high culture, Germany was coming to represent (to its foes, at least) not sophistication, but barbarianism. Small wonder that composers coming of age outside Germany in the early 20th century began to cast about for new visions of what music was, and ought to be. Two such composers were Maurice Ravel and Béla Bartók.

Maurice Ravel was born in 1875 in Ciboure, a French town close to the Spanish border. Upon enrolling at the Paris Conservatory, it became apparent that the music Ravel was compelled to write—inflected by Spanish music (Ravel’s mother was Basque) and, increasingly, the musics of Asia—sat uneasily with the demands of the institution, and the young composer was eventually expelled in 1900. In response, Ravel banded together with a number of other young musicians, poets and critics who saw themselves as artistic outcasts, forming a group known as Les Apaches. They met regularly to discuss art, argue about politics, and perform their compositions for each other. Ravel’s reputation as a composer rose steadily during this period, but when war broke out, Ravel eagerly enlisted. He was deployed as a truck driver, transporting munitions late at night just behind the front lines, often under heavy fire. (His friend Igor Stravinsky noted admiringly that “at his age and with his name he could have had an easier place, or done nothing.”) Ravel continued to compose after the war—he was by now generally regarded as France’s foremost living composer—but his experiences on the front had left him physically and emotionally weakened, and he died in 1937 at the age of 62.

In a 1911 interview, Ravel asserted that French music “has not the gigantic form of Beethoven and Wagner, but it possesses a sensitiveness which other schools have not. Its great qualities are clearness and order.... The French composers of today work on small canvases but each stroke of the brush is of vital importance.” If German composers were maximalists, Ravel was saying, French composers were miniaturists. His own music was a case in point. There is a clarity and intricacy to Ravel’s music, as well as lush and exotic color, due in no small part to his extraordinary skill as an orchestrator. Moreover, while some early 20th-century composers thought that a complete break with the past was necessary if music was to progress—Arnold Schoenberg being a particularly prominent example—Ravel did not follow their lead. In Ravel’s compositions, the past is everywhere present—but it is the past of myth, dream, and fantasy. There is no redemption on offer in Ravel’s music. What it offers instead is the consolation of beauty.

Béla Bartók took a rather different path. He was born six years after Ravel in the small town of Nagyszentmiklós, in the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1899, he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest to study piano and composition (he was already something of a piano prodigy). On a visit to a holiday resort in 1905, Bartók overheard a young nanny singing folk songs to her charges, igniting in him a lifelong interest in and dedication to the folk music of Central Europe. He began to travel into the countryside to collect Hungarian, Bulgarian, Romanian, and Slovak folk music; later he would travel as far as Turkey and Algeria to collect. “In order to really feel the vitality of this music,” Bartók wrote, “one must, so to speak, have lived it—and this is only possible when one comes to know it through direct contact with the peasants.” Though his early compositions had borne the mark of Richard Strauss in particular, his mature style is characterized by a thoroughgoing mastery of folk idioms: it is art music, sophisticated and urbane, that—as he himself put it—speaks the language of folk music as a “mother tongue.” In the 1930s, Bartók’s public opposition to the rise of fascism in Hungary began to attract hostility, and he was eventually forced to emigrate to America. He died there in 1945, just as World War II was ending.

Making authentically Hungarian music doubtless felt especially urgent for Bartók, given that Hungary had practically been legislated out of existence following World War I. (The redrawing of borders had caused Hungary to lose 71 percent of its historical territory.) But Bartók’s conception of national identity was not a racial one. He understood that Hungary was thoroughly multiethnic, and that the folk music that expressed Hungarian identity had deep roots extending all across the continent. Like Ravel, Bartók refused to countenance the idea that the musical future should renounce the past—but unlike Ravel, the past that Bartók sought to animate in his work was a real past, rather than an imagined one.

Violin Concerto No. 2 in B minor

Béla Bartók

Born: March 25, 1881, in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary

Died: September 26, 1945, in New York

Work Composed: 1937–38

SF Symphony Performances: First—January 1948. Pierre Monteux conducted with Tossy Spivakovsky as soloist. Most recent—May 2014. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted with Christian Tetzlaff as soloist.

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (2nd doubing piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons (2nd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, gong, 2 snare drums, and bass drum), harp, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 36 minutes

Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2 was written in 1937–38, when he was at the peak of his compositional powers. It was commissioned by his friend and collaborator, the violinist Zoltán Székely. Initially, Bartók wanted to write a big one-movement set of variations, but Székely insisted on a more traditional three-movement concerto. Eventually, they compromised: the second movement is a theme with variations, and the third movement is essentially a variation on material from the first movement. (Bartók teasingly wrote to Székely, “So I managed to outwit you. I wrote variations after all.”) The concerto, written just as Bartók was reluctantly realizing he would have to leave his homeland, is a defiant and life-affirming expression of Hungarian spirit.

The Music

The first movement begins gently, with simple chords on harp accompanying a five-note motif on pizzicato strings. The solo violin enters with a rhapsodic theme, and we are swept into a world of rapidly-shifting color and mood. The sinuous second theme, which uses all 12 tones of the scale, hints at atonality—but only barely. As Bartók would later explain, “I wanted to show Schoenberg that one can use all 12 tones and still remain tonal.” The fiendishly challenging cadenza features Bartók’s first use of quarter-tones: he instructs the violinist to slide infinitesimally above and below the notated pitch. In the syncopated, technicolor recapitulation, the string players are instructed to play pizzicato so forcefully that the string rebounds off the fingerboard. The movement culminates in abrupt, triumphant unison.

At the opening of the second movement, which takes the form of theme and variations, we find ourselves in very different musical terrain. Harp and strings build a delicate chord, and the solo violin enters with a contemplative theme. The first variation occurs against a dreamlike background of celesta and sparkling woodwinds. The third variation dispels the haze suddenly, and a sense of latent unease establishes itself. Each new variation brings a change of texture, taking us on an unpredictable adventure through sharply contrasting musical landscapes. The pizzicato strings and subtle snare rolls of the penultimate variation hint at war, before a haunting final variation brings the movement to a wistful close.

The third movement begins with a flurry of activity. The main theme of the first movement reappears, transfigured into an exuberant waltz. Percussive stabs burst forth from the orchestra as the solo violin whirls overhead. The boisterous mood gives way suddenly to a subdued atmosphere of suspense, given definition by delicate touches on celesta and percussion, only to be dramatically dispelled as the orchestra explodes into life once more. We are propelled ever onward through a series of richly textured musical scenes, the crackling energy never abating, until the concerto ends in a blaze of orchestral color.

Daphnis et Chloé

Maurice Ravel

Born: March 7, 1875, in Ciboure, France

Died: December 28, 1937, in Paris

Work Composed: 1909–12

SF Symphony Performances: First complete—December 1947. Pierre Monteux conducted. (The Suite No. 2 was first performed in July 1930. Artur Rodzinski conducted.) Most recent—June 2023. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (2nd and 3rd doubling piccolo), alto flute, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, cymbals, suspended cymbals, antique cymbals, tam-tam, snare drum, low snare drum, bass drum, tambourine, castanets, wind machine, glockenspiel, and xylophone), 2 harps, celesta, and strings

Duration: About 50 minutes

Ravel was commissioned in 1909 by Serge Diaghilev, the famous impresario of the Ballets Russes, to write a score for a ballet exploring the Ancient Greek myth of Daphnis and Chloé. As told by Longus, Daphnis and Chloé are two foundlings raised by shepherds on the island of Lesbos whose initial confused feelings for each other blossom into romantic love. Ravel clashed with Diaghilev from the beginning. Diaghilev wanted the ballet to echo classic Hellenic art; Ravel, on the other hand, was more interested in evoking “the Greece of my dreams”—essentially, Greece as portrayed by 18th-century French painters. Tempers flared once rehearsals got underway, with lead-dancer Nijinsky continually arguing with choreographer Fokine. Rehearsals were made still more fraught by the fact that, as Ravel drily put it in a letter to a friend, “Fokine doesn’t know a word of French, and I only know how to swear in Russian.” Shortly before opening night, Nijinsky’s performance of Debussy’s Prélude à L’Après-midi d’un faune caused outrage (it was perceived as unacceptably erotic); the scandal overshadowed the premiere of Daphnis et Chloé somewhat. Nowadays, however, Daphnis et Chloé is widely regarded as Ravel’s orchestral masterpiece. The work is often performed as a slimmed-down concert suite; on this program, however, the full ballet score is performed in a chorus-less version Ravel prepared at Diaghilev’s request.

The Story and Music

Part I opens with a barely perceptible shimmer of sound (Introduction). A languorous melody is passed from solo flute to horn, over dreamily shifting harmonies. It is morning, and we are in a grotto on Lesbos, consecrated to the Nymphs. Young girls and boys are coming to offer gifts to the Nymphs, as in the background, Daphnis is following his flock, soon to be joined by Chloé. The music builds to a glorious sunburst as the young people make their offerings. A graceful rhythm emerges, and the young people begin to dance (Danse religieuse). The dreamlike atmosphere is broken as the young girls notice Daphnis, and begin to dance around him. The jealous Chloé is swept into the dance, and the cowherd Dorcon tries to kiss her. The group proposes a dance contest between Daphnis and Dorcon, with the victor to receive a kiss from Chloé. Dorcon dances, and the young people imitate his clumsy movements (Danse grotesque de Dorcon). Daphnis comes forward to embrace Chloé, and a radiant group forms around them. After an elegant dance by Lyceion (Danse de Lycéion), a band of pirates bursts in, heralded by trumpets; the brigands abduct Chloé. Daphnis swoons, mad with despair. The Nymphs come to life, the orchestra summoning the unearthly atmosphere with washes of percussion and delicate flourishes in the woodwinds. The Nymphs invoke the god Pan, before whom Daphnis prostrates himself beseechingly.

Part II begins with unearthly harmonies heard from afar (Introduction). A distant trumpet calls, a murmur builds in the low strings, and with a crash, we find ourselves in a pirate camp on a rugged coastline. Pirates scurry about, carrying their plunder (Danse guerrière). The activity builds to a frenzy before coming to a stop, and the captive Chloé is brought in. Chloé performs a halting, tremulous dance of supplication (Danse suppliante de Chloé). She tries to flee, but is dragged back to resume her dance, finally collapsing in despair. The pirate leader carries her off in triumph—but then, an ominous rumbling starts up in the percussion section, and the atmosphere becomes suddenly unearthly. The ground opens, and the terrible specter of Pan appears. Everyone flees in fear except for Chloé, who is given a wreath.

At the opening of Part III, we are back on Lesbos, at the grotto of the Nymphs. Glorious swirls of orchestral color suggest the breaking of dawn (Lever du jour). Daphnis wakes, anxiously looking about for Chloé. She appears, and they throw themselves into each other’s arms. In tribute to Pan, who has saved Chloé, Daphnis and Chloé mime the tale of Pan and his water-nymph love Syrinx (Pantomime). Daphnis pledges his love to Chloé before the altar of the Nymphs, and the ballet ends with a bacchanal (Danse générale).

—Jenny Judge

About the Artists

Jun Märkl

Jun Märkl serves as music director of the Taiwan National Symphony, music director of the Indianapolis Symphony, chief conductor of the Residentie Orchestra of The Hague, and principal guest conductor of the Oregon Symphony. He previously served as music director of Orchestre National de Lyon, the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony, Basque National Orchestra, and Malaysia Philharmonic.

Märkl regularly guest conducts major orchestras in North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania, including the Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Boston Symphony, Bavarian Radio Symphony, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, NHK Tokyo, and many others. His expertise in the world of opera has led to long relationships with the Vienna State Opera, Berlin State Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Semperoper Dresden, Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, and New National Theatre in Tokyo. He makes his San Francisco Symphony debut with this program.

On recording, Märkl has an extensive discography of more than 55 albums. In recognition of his achievements in France, he was honored in 2012 with the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Märkl is highly dedicated to work with young musicians: for many years he worked as principal conductor at the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo and at the Aspen Music Festival. He teaches as a guest professor at the Kunitachi College of Music in Tokyo and founded the National Youth Symphony Orchestra of Taiwan. He studied in Munich with Sergiu Celibidache and at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa.

Leonidas Kavakos

Highlights of Leonidas Kavakos’s 2025–26 season include performances with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, NHK Symphony, NDR Symphony, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, and conducting engagements with the Czech Philharmonic, London Philharmonia, Barcelona Symphony, and Minnesota Orchestra. In 2022, he founded the ApollΩn Ensemble, a chamber group of elite Greek musicians, and in 2025 he takes over as the artistic director of the “Classic Revolution” Festival at Lotte Concert Hall in Seoul.

Kavakos’s award-winning discography includes the Brahms Violin Concerto with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and Riccardo Chailly on Decca, and play-directing the Beethoven Violin Concerto with the Bavarian Radio Symphony on Sony Classical. He was named Echo Klassik Instrumentalist of the Year for his recording of the complete Beethoven sonatas with Enrico Pace. With Emanuel Ax and Yo-Yo Ma, Kavakos has released a series of trio recordings, and he has recorded Bach’s violin concertos with the ApollΩn Ensemble.

Kavakos curates an annual violin and chamber music masterclass in Athens, where he was born and brought up in a musical family. In 2022, he was elected by the Academy of Athens as a member of the Chair of Music in the Second Class of Letters and Fine Arts for his services to music. In 2024, he was appointed professor of violin at the Basel Academy of Music. Kavakos plays the “Willemotte” Stradivari violin of 1734. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut with a March 1994 recital and debuted with the Orchestra in April 2005.

Postconcert Conversation Host

Following Thursday Matinee

Sarah Cahill is a pianist who has worked closely with composers John Adams, Terry Riley, Frederic Rzewski, Pauline Oliveros, Juilia Wolfe, Roscoe Mitchell, and Lou Harrison, among many others. She hosts Revolutions Per Minute every Sunday from 6:00pm–8:00pm on KALW 91.7 and is a regular speaker at the Los Angeles Philharmonic and San Francisco Symphony, where she has also performed at SoundBox. She serves on the Music History and Literature faculty of San Francisco Conservatory of Music and is a graduate of the University of Michigan.