In This Program

The Concert

Thursday, February 19, 2026, at 7:30pm

Friday, February 20, 2026, at 7:30pm

Saturday, February 21, 2026, at 7:30pm

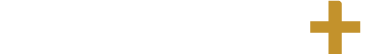

Jaap van Zweden conducting

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Opus 36 (1802)

Adagio molto–Allegro con brio

Larghetto

Scherzo: Allegro

Allegro molto

Intermission

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Opus 92 (1812)

Poco sostenuto–Vivace

Allegretto

Presto

Allegro con brio

Lead support for this concert series is provided by The Phyllis C. Wattis Fund for Guest Artists.

Program Notes

At a Glance

The Second Symphony is often thought to mark the end of Beethoven’s early period, but is perhaps better thought of as a transition piece into his middle, or “heroic” period, when so many of his most impactful works were written. The Seventh Symphony comes from the other side, a transition into Beethoven’s late period. Both works show Beethoven’s singular aptitude for expanding and reinventing musical form. What he begins in the Second Symphony he expands and expounds on in the Seventh—particularly his use of an expanded introduction, the development of the scherzo, and obsessive use of rhythm. These works together frame Beethoven’s artistic evolution over perhaps the most important decade of his career.

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Opus 36

Ludwig van Beethoven

Baptized: December 17, 1770, in Bonn

Died: March 26, 1827, in Vienna

Work Composed: 1801–02

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1916. Alfred Hertz conducted. Most recent—October 2023. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 35 minutes

In today’s concert culture, it is rare to perform two symphonies on one program. Often, orchestras will follow the well-loved recipe of an overture, a concerto, intermission, then a symphony. For Beethoven and his audiences, however, performing two symphonies on one program would have been mere courses in a long tasting menu of his works. So it was with the premiere of the Second Symphony, which also included on its program the premieres of his Third Piano Concerto, the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, and a repeat performance of his First Symphony, which had been premiered in Vienna almost exactly three years earlier.

Perhaps because we know so much about his life, there is often the inclination to ask whether Beethoven’s music contains in it some hidden meaning or autobiographical insight. The Second Symphony may serve as a gentle reminder not to conflate too closely the music with the maker. Beethoven was at the beginning of an incredibly fruitful compositional period in his life when he completed the Second Symphony. It was also the period when he penned his famous missive to his brothers, now known as the “Heiligenstadt Testament.” In it, Beethoven grapples with the profound hearing loss rapidly encroaching on his life. Despite the composer’s anguish over losing his hearing, the Second is the most blithely happy sounding of all his symphonies. He had written in correspondence that he was trying to forge a “new path” in his life, and in his music.

The Music

Classical symphonies before Beethoven often had a short first-movement introduction to set the tone for the work. However, the Second Symphony contains the longest introduction in the repertoire to that point, replete with an enormous range of characters and dynamics. Suddenly, almost without warning, the introduction shifts into a vibrantly energetic Allegro con brio. The movement vacillates between unabashed joy and capriciousness. Beethoven writes an enormously long coda in the first movement. Already, he is starting down his new path, playing with form and structure to expand sonata form and listeners’ expectations.

The second movement Larghetto brings out a sweetness new to the young composer’s compositional style. It is earnestly tender and yet has moments of coy playfulness. A common debate among Beethoven interpreters is over the appropriate tempo, a particular fascination in this movement. His 1817 metronome marking notes the eighth note at 92 beats per minute, a fluid tempo that is much faster than many conductors have chosen. In the time-worn debate around intention and interpretation, this movement has one of the largest variances in Beethoven’s symphonies. The movement can range from introspectively slow and measured to dance-like and with a sense of impertinent whimsy.

Beethoven again shifts away from the classical symphonic form in the third movement by eschewing the regular minuet in favor of a scherzo. Whereas the minuet connotes a courtly dance in three, scherzo means “joke” in Italian and is often dramatically faster than its minuet counterpart. Beethoven would incorporate scherzos into all his subsequent symphonies except for the Eighth, which again has a minuet (albeit one that strays from the classical version more than it adheres to it).

The finale begins with a hiccup and a growl, setting off a string of comedic gestures. There are two contrasting themes, one sweet, the other playful. At first it seems that the movement will be compact, in the Classical style. But then Beethoven embarks on the coda. The coda grows and grows until it becomes nearly one-third the length of the entire movement. It is yet another way that Beethoven plays with expectations and asserts his own perspective and compositional style without completely eschewing the classic symphonic form. The audience at the premiere would have understood the work within the context of a symphony, but they would have certainly been aware of many of the ways Beethoven was trying to propel the genre in a new direction.

Though the Second Symphony received mixed reviews, the premiere on April 5, 1803, was a general success. It was not, however, without its trials and tribulations. There was only one rehearsal, which went from 8:00am to 3:00pm nonstop (something no musicians union would allow today). Beethoven’s pupil, Ferdinand Ries, was frantically copying trombone parts for the oratorio at 5:00am on the morning of the concert. Audiences vied for tickets, which sold at twice and three times the normal price. One of the drawbacks to becoming the presumptive symphonist heir apparent with one’s first symphony was that subsequent symphonies were all judged according to that rubric. Comparisons were bound to be made between the First and Second Symphonies. Perhaps surprising to today’s audiences, it was not common practice to perform pieces year after year in public the way orchestras do today. Until the mid-19th century, audiences were musical neophiles who wanted to hear the latest and greatest compositions. It was not until after Beethoven’s death that a culture of hearing the works by “genius” composers, to try to understand their prowess, became routine. This is largely because of Beethoven, one of the first composers to meticulously retain even his drafts, because he already considered himself part of the great lineage of composers even during his own lifetime. One critic said, “the First Symphony is better than the more recent one because it is developed with lightness and is less forced, while in the Second the striving for the new and surprising is more apparent.” Beethoven was straddling two worlds with the Second Symphony; on one side, following in the footsteps of Mozart and Haydn, and on the other, developing his own novel musical voice.

Symphony No. 7 in A major, Opus 92

Ludwig van Beethoven

Work Composed: 1811–12

SF Symphony Performances: First—February 1914. Henry Hadley conducted. Most recent—April 2024. Jukka-Pekka Saraste conducted.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: About 38 minutes

While Beethoven still retained some of his hearing when he composed his Second Symphony, by the time he composed his Seventh, he was likely nearly completely deaf. And yet, the composer conducted his works at the concert, despite not being able to hear anything but the very loudest passages. The concert premiere of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony on December 8, 1813, was probably the most successful concert of his lifetime. The fervent praise was in fact for Beethoven’s other work on the program, Wellington’s Victory. That piece depicts the marquess (later duke) of Wellington’s triumph over Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s older brother and king of Spain, at the Battle of Vitoria. Wellington’s Victory was so enormously popular that the musicians were engaged for a series of concerts in January and February of the following year.

As was typical in Vienna at the time, many of Beethoven’s concerts were funded by the composer himself. That means he hired whoever he could afford or find, and therefore his music was often played by amateur or semi-professional players. However, because this concert was a benefit for Austrian soldiers, some of the most famous composers and musicians of the day were on the roster. Ignaz Schuppanzigh, the famous string quartet leader who premiered quartets by Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert, was concertmaster; Louis Spohr played assistant concertmaster; and Joseph Mayseder, the second violin of the Schuppanzigh Quartet, played principal second violin. Giacomo Meyerbeer, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Ignaz Moscheles (a famous pianist) all played extra percussion in Wellington’s Victory, with Antonio Salieri acting as sub-conductor for percussion and artillery. This is all to say that the performance of the Seventh Symphony would have had superb musicians.

The Music

In the Seventh Symphony, Beethoven opts again for a long introduction, making the introduction to the Second Symphony seem trifling in comparison. The introduction is regal at times, dramatic at others, but is always unfolding dramatically through rhythmic tension, diminution, and anticipation. What Beethoven may lack as a melodist he more than makes up for in rhythmic excitement. Toward the end of the introduction, the flute and oboe and the violins start to trade off a repeated E. This single note is repeated 61 times in a row before the romping melody of the Vivace takes off at full tilt, like riding a horse who refuses to slow to a trot. It is difficult to imagine another composer repeating a single note as such without being accused of insipidness. In Beethoven’s hands, however, this repetition is enthralling, full of anticipation. It is but the first taste of how Beethoven’s use of obsessive rhythm and mastery of structure make this symphony so captivating and exciting. Throughout the movement there are scalar hiccups that bring the energy to a halt before Beethoven returns to the same rollicking gallop. There is an extensive coda in the first movement, which we will again see in the fourth movement. The low strings meander, like a mosquito doppler effect with the pitch turned way down. This chromatic oscillation continues to the final coda with a final restatement of the theme and an exultant finish.

The second movement is not a slow movement as would have been expected. It is marked Allegretto, or slightly slower than Allegro. It only feels slow relative to the often breakneck tempos of the other movements. Again Beethoven utilizes a rhythmic pattern as an organizing feature. Dum-da-da-dum-dum, almost like the slow marching of soldiers’ feet. (Remember that this symphony was premiered at a benefit concert for soldiers.) The movement so moved the audience that they demanded an encore performance during the concert. It is a testament to Beethoven’s ability to create such a powerful effect out of an ostinato rhythm, even when the harmony and melody hardly do anything in the classical sense of harmony and melody. Leonard Bernstein called it “one of the most unremarkable melodies ever written,” but at the same time, Beethoven always puts just the right note at the right place, “as if he had some private telephone wire to heaven which told him what the next note had to be.” In Bernstein’s estimation, the very unexpectedness of Beethoven’s writing is what makes it so undeniably perfect.

The third movement is an exuberant scherzo-trio; or more accurately, a double scherzo. Beethoven elongates the A-B-A form to A-B-A-B-A. True to the nature of a scherzo (“joke” in Italian), Beethoven plays with timing, sometimes unexpectedly cutting out a bar of a phrase. In the trio section, the winds swell like an over-enthusiastic squeezebox, and the orchestra plays with the time though hemiolas (two-against-three rhythm) and accents on the offbeats. Beethoven emphasizes this in the second horn solo, which Robert Schumann likened to the sound of repeated burping, but which horn players affectionately refer to as “the bullfrog solo.” After the final scherzo, Beethoven plays a last joke on the listener by starting yet another trio for two measures only before ripping to the end of the movement with a surprise rapid-fire five-note cadence.

Finally, the finale—the most ebullient movement of them all. After a gripping call to attention at the opening, the orchestra wings into a folk-like dance melody, with the accompaniment hammering the offbeats. The conductor Sir Thomas Beecham said it sounded like “a lot of yaks jumping around,” which is an apt description given that Beethoven borrowed some of the thematic material from an Irish folksong, “Save Me from the Grave and Wise.” The long coda of the movement centers around chromatic oscillations from the low strings, first between G-sharp and A, then moving downward to E and D-sharp. Above it, the violins trade musical fisticuffs until the inexhaustible fanfare heralds the joyful end.

—Alicia Mastromonaco

About the Artist

Jaap van Zweden

Jaap van Zweden is music director of the Seoul Philharmonic and music director designate of Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. Among his past music directorships are the New York Philharmonic, where his tenure included 31 premieres and the reopening of David Geffen Hall, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which was named Gramophone’s Orchestra of the Year under his leadership. He has conducted the Vienna Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Berlin Staatskapelle, London Symphony, Boston Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among many others. He made his San Francisco Symphony debut in October 2012, led this season’s Opening Gala with Yuja Wang in September, and is leading the Orchestra in a three-season cycle of Beethoven’s nine symphonies.

This season, van Zweden undertakes European and Asian tours with Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and rejoins the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, and Antwerp Symphony, where he is conductor emeritus. In the United States, he returns to the Chicago Symphony and leads his first US tour with the Seoul Philharmonic. In Asia, he returns to the NHK Symphony Orchestra and the Hong Kong Philharmonic.

Van Zweden’s discography includes acclaimed releases on Decca Gold and Naxos. With the New York Philharmonic, he recorded David Lang’s prisoner of the state and Julia Wolfe’s Grammy-nominated Fire in my mouth. With the Hong Kong Philharmonic, he conducted the first full Ring cycle ever staged in Hong Kong, and his performance of Parsifal received the 2012 Edison Award for Best Opera Recording.

Born in Amsterdam, van Zweden was appointed the youngest-ever concertmaster of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at age 19, and began his conducting career in 1996. A winner of the Concertgebouw Prize and Musical America’s 2012 Conductor of the Year, he founded the Papageno Foundation with his wife, supporting young people with autism through music, housing, research, and innovation.